I wanted to work into a soft and easy place. I wanted my collection to reflect something bigger and maybe more universal than just my pain. So, I guess that’s where the idea of “everything asking for mercy” came from—this sort of collective plea for peace.

Ginna Richardosn Luck

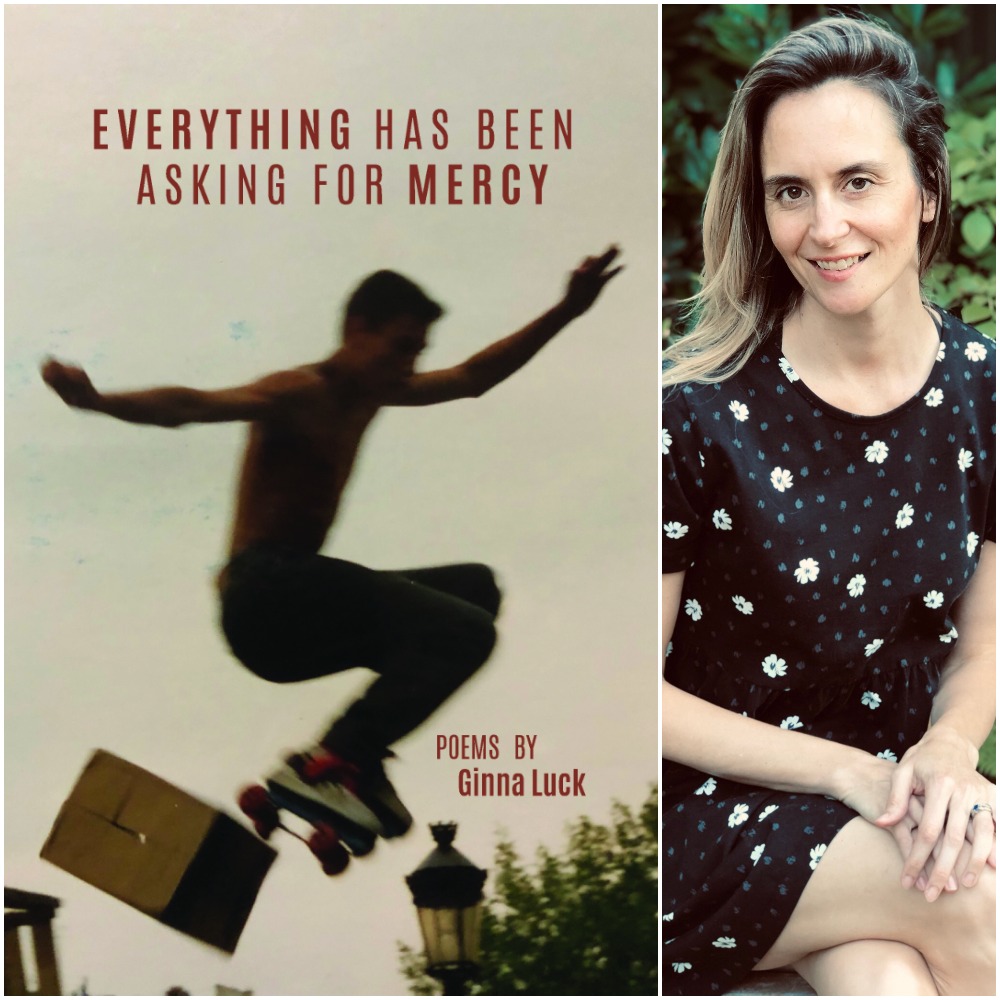

Pif’s poetry editor, Tristan Beach, interviewed Ginna Luck on the occasion of her debut poetry collection, Everything Has Been Asking for Mercy, published by Finishing Line Press in March, 2020. Tristan and Ginna spoke about the years-long process of writing the collection, “opening up” through writing, and exploring some of the collection’s core qualities, including vulnerability, strangeness, and connecting the personal with the universal.

Individuals are identified by their initials. This written interview was conducted virtually, over Facebook Messenger.

Tristan Beach: The title of your debut collection, Everything Has Been Asking for Mercy, is so tender, just, and self-evident. A reminder to be generous and gentle. Could you speak about how you came to write this collection and from where or how the title emerged?

Ginna Luck: I actually didn’t want to write this book in the beginning and ended up going to grad school and getting my MFA in fiction—only to realize much later that I needed to focus on something different. I had been struggling through a health crisis for about four years at the time, so I began writing poetry out of a need to escape some of the mental and physical pain I was experiencing. So I started writing my book thinking I was just writing about chronic fatigue, which is the illness I have. But then I realized about a year into the book that I was really writing about all the history that lead me to depletion and illness.

As far as the title, it comes from a poem in the collection. I thought it expressed perfectly what I tried to articulate in many of the poems. Although I was not always good at being kind to myself during many of the years I was sick, I wanted to work into a soft and easy place. I wanted my collection to reflect something bigger and maybe more universal than just my pain, though all the poems are about me. I never wanted to just write a book all about myself. So, I guess that’s where the idea of “everything asking for mercy” came from—this sort of collective plea for peace.

I needed to write myself out of the same old emotions that I had for as long as I can remember, which I still get stuck on. I wanted it to be ugly and beautiful and raw.

TB: Thank you for that response. How has the expression or transformation of that pain into words (into poems) allowed you to connect the personal to the universal?

GL: For me, writing poetry was never about turning inward. It was about opening up. I find I am able to more accurately articulate something if I can come at it from multiple angles, not just my old and tiresome pain, but from a place where I feel connected to nature and people. To do that, I had to think of myself outside of my illness and then imagine something new. I had to connect with a perspective that was not always one I wanted to look at. I thought if I could be vulnerable, I could connect to a more universal feeling and reach many more people. If I could be vulnerable in that way, totally out of my comfort zone, I would arrive at something new, which was always the goal. I needed to write myself out of the same old emotions that I had for as long as I can remember, which I still get stuck on. I wanted it to be ugly and beautiful and raw.

TB: I think of the vulnerability you mention, which is evident in these poems, as inviting. Although sometimes the rawness of experience can be off-putting, going at it from different angles—to show the pain and the beyond of that pain as multi-faceted—opens the door to the reader. This isn’t just your experience anymore, it’s everyone’s.

GL: Exactly!

TB: Another quality I’ve noticed in this collection is that of strangeness. How do you feel strangeness operates within or inhabits your poems?

GL: I am drawn to strangeness in writing, art, life. I think it comes from a place of stubbornness, wanting to always be different, and one of insecurity—never really feeling okay in my own body. I found that weirdness sometimes better exemplifies the truth, if that makes sense. I think if we see the same thing over and over again it no longer means anything. So, I can better articulate an emotion if there is an element of strangeness. For example, I could write “I feel alone.” But it sounds much truer to me when I write, “I live in an orphan vessel” (from “It Hurts To Not Be What I Am”).

TB: This makes perfect sense to me as a reader. Even the line “I live in an orphan vessel” has its own logic I can connect with. Would you say that strangeness in your work also connects to the idea of “opening up?”

GL: Yes, I think it does. It is that feeling of being outside of yourself. And I think too there is a strangeness in the world and nature that we witness and feel but cannot always understand. But it still means something, and if we can connect to what we cannot fully understand, then maybe we can also begin to let go of the same old language and thoughts that we are accustomed to. I do not write nature poems though, haha! . . . I’m just talking about the energy of being open to all different ways of seeing myself in the world. We are all trying to say the same things in different ways.

TB: What is something essential or lifegiving that you’ve learned during the process of writing this collection. Is this something you hope or intend for your readers to learn as well through your poems?

GL: I learned a lot of things, mostly that it’s okay to be a very sensitive and emotional person. Writing my book didn’t necessarily teach me that, but the process allowed me to be myself, something I had never fully done before. I had spent my entire life trying to close down my emotions which led me to some really damaging habits and experiences, some of which I am still trying to work through. In that sense, the process of writing was extremely lifegiving as it became a tool to better navigate myself through a very difficult time. I like to think I was taking responsibility of my illness. No one likes the feeling of being helpless, and chronic fatigue didn’t just happen to me. Nothing ever just happens. There is always a history, so I wanted to examine that history. And that’s what my book became. So, I was really learning how to be myself, which sounds kind of funny since I am not young. But I would like to be an example, especially for my kids.

TB: I think most of us are still learning who we are and learning to be ourselves. Our dominant culture doesn’t value sensitivity and emotion, and I think a lot of people develop habits that hurt their ability to feel for each other.

GL: Yeah, it’s sad.

TB: So, I see your point.

GL: Also, I don’t ever imagine anyone will learn anything from my book. I don’t like the idea that I know more than everyone else. I honestly think a very small group of people will read my book and I hope when reading it they feel something, even if they can’t really articulate it at that moment. I don’t know. I don’t read poetry to learn something always—but to feel.

TB: I think what you said is great. We need to remind ourselves that sometimes when we come to poetry, we can inhibit or sabotage our experience if we are too concerned about what we’re getting out of it or what it is supposed to mean.

I’d like to conclude this interview with a question that I’ve heard Rebecca Brown pose during a commencement address; I keep encountering it in my own art and relationships. I’m wondering how you would respond to it as well, and whether or not you could discuss your response. It goes, and I’m paraphrasing, “The world is on fire; why am I making art?”

GL: That’s a big question … I think I’ve answered that question in a roundabout way in all of my other responses. I’m making art to be engaged and connected to the world and to all that it encompasses. Maybe I’m not doing this in a direct way, but in a quiet and more personal way. That is how I operate.

___

Ginna Luck’s poems have appeared in Radar Poetry, Gone Lawn, Hermeneutic Chaos Journal, Rust + Moth, Leveler Poetry, Up The Staircase Quarterly, and others. She has been nominated for two Pushcart Prizes. She received her MFA from Goddard College. Her first full-length collection, Everything Has Been Asking for Mercy, was published by Finishing Line Press. She teaches elementary school and lives in the Seattle area with her family.

Tristan Beach is the poetry editor for Pif Magazine. He currently co-organizes the Holyoke Reading Series in Seattle. From 2014 to 2017, Tristan taught English at various institutions across China. Before that, he was an editor for Portland-based literary journal Conium Review and has been involved with several other journals and small presses, including Copper Canyon Press, Coffee House Press, Pitkin Review, and Clockhouse.

The featured photograph is by a Wisconsin based artist JJ D’Onofrio.