I first met Sarah Cannon, at the time Sarah Kishpaugh, when I came into my MFA program at Goddard College. As I began my first semester, she was graduating. I listened to the graduate reading and attended the graduation ceremony of the Fall 2014 class, all of whom appeared as superheroes to me who was still questioning my sanity after deciding to, with a toddler at home and being pregnant, pursue an MFA. However, to this day I remember the readings of three women: Samantha Kolber Pytak, Alison Bailey, and Sarah Cannon. And I am happy I have been in touch with them all ever since and that now we celebrate Sarah’s success.

Sarah Cannon was born and raised in Seattle (the north-end neighborhoods) and has been active as a community education writing instructor at places in the Seattle area like Verdant Health and Edmonds Community College. She is a mom of two teenagers with whom she lives in Edmonds, WA.

She might have had different plans for life when she got married to Miles Kishpaugh. She might have imagined what their happily-ever-after would look like. However, on an October morning in 2007, she received a phone call and learned that her spouse of seven years had been severely injured at the workplace by a falling tree branch. The same morning the life she knew of ceased to exist, and she became the wife of a man with a traumatic brain injury. The brain injury took charge of her marriage and became the omnipresent yet emotionally consuming topic of her writing.

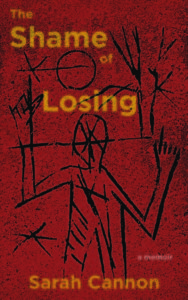

Eleven years later, after enduring a hell of a ride on the life’s rollercoaster, Sarah Cannon debuted as an author with a memoir titled, The Shame of Losing.

The book that is short in form (120 pages) is charged with feelings and sudden changes in voice and style that resembles a rollercoaster. As a reader, I wasn’t able to put it down. Up and down I rose and fell following Sarah on her journey of witnessing, fighting, surviving, and letting go of the injury that had changed her family forever.

I met Sarah for lunch in Café Press on Capitol Hill, close to the campus of Seattle University where she now works. I was curious to know more about her experience of publishing her first book and her life post-divorce, as a single mom and a writer.

When we teach writing, we tell our students how important it is to find an inciting incident of a story, the one that propels the protagonist to set herself off to an adventure. I was wondering if you had imagined debuting with a memoir back in 2013 when two of your essays about loving a survivor of a traumatic brain injury were published in Modern Love and Salon.com? If so, did that long-time imagined book have many similarities to The Shame of Losing?

Sarah: I did not imagine I would write a memoir. I thought only celebrities or retired politicians wrote memoirs, and that you had to pronounce “memoir” in French, which sounded kind of snooty to me. I thought that you had to be really sophisticated to have a story worthy of telling. I came to grad school thinking I was going to learn how to write a movie script. I was fascinated by the drama in my life and wanted to build from it and learn that form. I was interested in entertaining others, not examining myself.

As I was reading Michel Obama’s memoir last night, and as the word “Becoming” took up space in my mind, I was curious to know how your story became The Shame of Losing I held in my hand. How did the journey from the initial idea to the polished manuscript ready for printing look like?

Sarah: I began notating the events in the hospital that ended up in the book as they were happening back in 2007. Really, I turned very bad fiction into creative non-fiction during my last semester at graduate school at the behest of smart advisors and my own self coming to terms with telling a painful story, telling my truth. I scratched at that same document for two more years before sending twenty pages to the press that eventually” bought” it. (Bought is in quotes b/c there was no advance – standard with smaller presses.) I appreciated that Red Hen had an open, free submission process – that was refreshing after a handful of agency rejections. I remember I sat in my car crying when I got that email from the editor, Kate Gale. She wrote, “I love it, send me the whole thing.” I cried, and then I got to work. I let her assistant know that I would have the rest for her in a month, and they really held me to that deadline, checking in every week. I was so scared that the only good pages were the few I had sent. What happened after I sent the whole thing was a lot of waiting. They finally accepted it, and that was a real rush. I had an attorney look over the contract before signing, and then I was officially in the Red Hen queue. That was in 2015. I had some contact here and there from the wonderful people who would be editing the manuscript, but real production didn’t start happening until last spring.

What were your biggest doubts and fears along the way?

Sarah: What if no one reads it? What if everyone reads it? What if everyone hates it? What if everyone loves it? Pretty much a lot of self-torture.

What kept you excited?

Sarah: The thought of connecting with readers and writers was exciting. Also, a real product, in book form, of my labor. The idea that Reese Witherspoon might read my book and want to consult with me on how to adapt it into a quality film for a broad audience. I’m joking, but not really. I always wanted everyone to know about how a brain injury is an ambiguous loss – how it’s not just about football players or soldiers. Wanting to make and share something beautiful that was created from something tragic kept me going, though I’m not sure the word is excited. Sometimes I wanted to puke thinking about my story being in the hands of someone judgmental or rigid.

When we work on stories from our lives, it is hard to look at ourselves as the story’s protagonist and to remain neutral and critical to how our characters appear on the page. How did you deal with this? Of what importance was sharing your drafts with the people you trusted?

Sarah: I had some good advice from a writer I really admire who I was lucky to workshop some pages with after grad school and before I submitted the manuscript. She knew I had a lot of content and that not only was there an injury, but there was a divorce. My book was tricky: how do you write about divorcing a person with a brain injury without feeling like a jerk? She made it easy for me. She said, “Don’t be a dick. Just remember that as you’re revising. Because a lot of this feels angry, even though it’s important.” I never felt like this wasn’t my story to tell, because it was my version of the truth, and I was there for all of it. But I was snarky at times, pissed at my ex and my family and friends, and I needed to work on that through revisions. Combing through the manuscript and making sure I was as compassionate as I could made my book better. I realized after a while that the whole thing is like one long love letter. I didn’t need to be a jerk. I only had to be true to myself and fair to others. As for sharing drafts, being in a creative writing program and having professionals with published works make thoughtful commentary was nearly enough for me. Sharing parts with a trusted writing group is a good idea. I shared my thesis that I naively thought was ready with a few friends I respected as readers. I had a few comments that I took to heart, particularly that some parts needed levity since the topic was so heavy. I never gave my drafts to my mom, who repeatedly asked to read it.

How did it feel when you had your book in your hands for the first time?

Sarah: Amazing. I love the size and weight and feel of my book. It’s 120 pages, which I love. I love small books. More agents and bigger publishers should take chances on small works that aren’t poetry in my opinion. I sniffed it and read it from beginning to end in one sitting – a real book in my hands that I wrote and imagined and produced! No one did that for me, no one paid me. My significant other read it in a few days too. I read it again as he was reading it and he was like, “Really? Again?” I don’t know. It’s been exciting and scary. It’s been hard to concentrate on anything else besides my book and my family these last six months. Or five years.

During my lunch date with Sarah, we talked about the feeling of shame a woman has over not living up to her potentials and expectations, to her family’s potential and expectations. This ever-burning question reminded me of the words by

Sarah: That’s a tough one. The Shame of Losing is thusly titled because so much shit happened in such a short amount of time that I was really punch-drunk by life. I still am to some degree. You don’t get married and have kids thinking your destiny is to survive a near-death accident alongside your spouse you barely got to be with pre-kids. I don’t know anyone who gets married thinking, “Well, if all this ends up sucking, I’ll just get a divorce and raise my kids by myself.” And I didn’t know another person like me in my life as a mom in the suburbs of Seattle. When you’re isolated by your life circumstances, you become lonely. When you’re lonely, you can easily confirm your loneliness and become more depressed by making comparisons to your peers. One doesn’t earn multiple degrees with hopes of balancing a freelance career with housecleaning, dog watching and serving lunch to elementary-school-aged kids. (All awesome jobs, by the way – they just don’t add up to much when you have to support children by yourself.) These are things I still struggle with, so no, I don’t think I’m entirely rid of my shame-ridden pathos in that regard.

I don’t feel like a loser, to the contrary – I have learned so much, and I have a lot to be proud of. But I think there is a lot to be said about the psychology of your family-of-origin when traumatic events happen. There’s this undercurrent of free thinking in the culture in which I was raised: you are in control of your outcomes in life, so if bad things happen, you must be bad. How can you possibly still be struggling financially? Wasn’t that accident ten years ago? If only you had made better choices. He looks fine. Where are you working these days? I’ve heard all of this and more – friends, co-workers, family. It’s exhausting to explain to middle-class and upper-middle-class people who I guess have not become unglued over tragedy, that you are doing the best you can. I was raised to be a yes person and to perform and to please. I know now that the questionings are the curiosities and anxieties of others, not a reflection of my failures. I don’t owe anyone explanations for how I’ve lived my life. It’s been a been a huge relief to realize that I don’t have to let myself feel bad for letting someone down because my life story did not have a traditionally happy ending.

Do you see The Shame of Losing as an act of closure and letting go? Of your marriage, of your anxieties, of writing about TBI?

Sarah: Yes, I do. I used to obsess over the politics that affect people with traumatic brain injuries, or any vulnerable population, really. Workers’ Compensation, Social Security Disability Insurance, Low-Income Housing, Food Scarcity. I’m still concerned with those issues, but they aren’t a nightmare for me anymore, and as a single mom, I’m finally getting my shit together. You don’t always know why you’re writing something. I think that I was writing this story to not only understand and share what I was enduring but also to move through a process of grief, the kind of grief I wasn’t allowed to have by the culture. If you lose someone who is still physically here, there is no funeral.

There is no eulogizing what was lost, and there is no public ceremony. Also, you are supposed to be a hero and overcome your obstacles. Taking control of the narrative helped me process the ambiguous loss. And putting original work out there that I felt was needed in the world has helped ease some of the loneliness. I’ll always be a little anxious. That’s how I roll. I’m anxious over what I will do next, not that I have let go, you know? Like when you’ve invested all this time and energy into advocacy and also a creative output, and it’s done. What now? I sense movement inside my heart, and a lifting. I know I won’t feel guilty if I don’t continue to fight as hard as I have. I feel I have nothing to prove.

What are your hopes for the future?

Sarah: I want to support my kids so they can go to college if that’s in the cards. And I want to edit a book with the photos of “vintage” motel signs along Aurora I’ve been capturing and commission some poems for it. And I want to write a teleplay about a single mom who rents out rooms in her house that she is at risk of losing. And I want to take a vacation somewhere warm where there are monkeys and sea turtles. And I want to develop an app that helps indie authors promote their work. And, and, and. I have a lot of ideas!

Could you share with us 5 memoirs that changed your perspective?

Sarah: The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby

My Body is a Book of Rules by Elissa Washuta

The Lover by Marguerite Duras

Stop-time by Frank Conroy

Now the Day is Over by Joan Fiset