All my life I thought of books as doors to conversations. On an opening verse of a poem, a beginning paragraph of a story, or the first page of a novel, I would start a conversation with characters and their writers. The more white space a writer creates for me, the more intense our dialogue becomes, and the more I love the book. Because of this habit, and because I always have new questions for my literary interlocutors, I read slowly, returning several times to the words I most enjoyed.

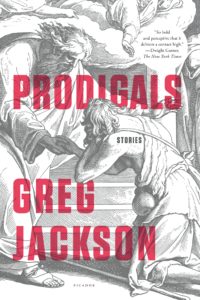

One of the books I have been rereading lately is Greg Jackson’s debut collection of short stories, Prodigals. Perhaps, I wouldn’t have yet picked up the book if I didn’t attend a conference where I was introduced to his voice and work. In November 2016, Greg Jackson won The National Book Foundation’s 5 under 35 award—the prestigious honor of being one of five writers under 35 expected to make a lasting impression on the American literary scene.

A perk of being a writer and an editor is that I get to reach out to the authors whose words amazed me and ask the questions I have been reciting in my mind. Did 5 under 35 come with pressure? And what has changed in the writer’s life since the award? A few months after, Jackson explains that the worst pressures are all self-generated and internal.

I wish I could say my life has changed dramatically, that people are stopping me on the street to shake my hand and so forth, but this just isn’t the case. It also isn’t true that magazines accept my stories at any greater rate: it’s still mostly rejections. As for the challenge of making a career as a fiction writer, that never seems to diminish; and the difficulty of writing good fiction stays pretty constant too. The better you get, the higher your standards for your own work get, and the more editors wish you would just go back to writing what you used to write when you were starting out and had fewer pretensions.

Prodigals are artists, seekers, eccentrics, and children of privilege, the edgy but sensitive characters that, like everybody else, search for identity, love, happiness or home. However, quite a few responses and critiques to the collection said that Prodigals was a satire to the upper middle class (the environment your characters came from). In my opinion, a satirical writer doesn’t care to save the souls of his characters, which is something I felt that you had been doing. Was it your intention to be satirical? Did you agree with the reviewers or did they surprise you?

I appreciate the sensitivity of this question. I have been surprised by the response from critics. Yes, the book takes aim at the mythologies and mores of the upper middle class, but I didn’t write it to be satire, and I certainly didn’t write a book about the “1%,” as I sometimes fear people will assume when they hear that my book “skewers the elite.” I also don’t concern myself exclusively with the well-to-do in the collection. If I commit any sin, I think, it’s writing about the segment of society that reads, writes, and publishes books, which can’t help hitting close to home, I guess.

But let’s speak frankly: Satire is safe. In its harshness and exaggeration we lose all meaningful sense of complicity and implication; the characters seem cartoonish, the scenarios overblown. Satire poses as social commentary, but in offending and challenging no one, in posing as incisive while trying at every turn to charm and amuse, it fails to touch anyone at the seat of her being and describes a society we feel we can stand in easy judgment of because it is a society to which none of us properly belongs. I think you put it nicely above when you say “a satirical writer doesn’t care to save the souls of his characters.” The satirical writer generally doesn’t even seem to believe people have souls.

I want to take everyone’s problems seriously, even the relatively fortunate and even those, like me, who have a hard time taking their own problems seriously because they and their problems are first and foremost to them absurd. I think people grow uncomfortable when you look at privilege squarely, with neither condemnation nor approval, and perhaps most of all when you forgo using the term itself as a way to diminish and protect its beneficiaries—or to pretend the lives of the privileged are one thing, uninteresting, and understood.

I also noticed that most of your stories flirted with the idea of the transience of time. Preparing these questions, I remembered what Junot Diaz said in the Introduction to The Best American Short Stories, 2016 edition. He said that the short story as a form “captures better than any other what it is to be human—the brevity of our moments, the cruel irrevocability when those times places and people we hold the most dear slip through our fingers,” and I realized how your collection does the same. It seemed to me that all your characters came to the point when they believed that they were running out of time to change their lives.

That’s a lovely quote . . . Do my characters believe they are running out of time to change their lives? I don’t know. Many are torn between the feeling evoked in the title of Grace Paley’s second story collection, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute—that it is never too late to change everything—and, on the other hand, enough self-knowledge to doubt that the snags of personality on which they keep catching will ever really go away. It’s funny because most of my characters are skeptical of the myth of identity, and I’m skeptical of it too, but they seem to be at that age when, while life is by no means set, you have seen yourself behave the same way enough times to doubt that you are going to go to sleep one night and wake up someone else.

Perhaps though there is something inherently literary about my characters, in that like me, and like most writers, they are attuned to the fleetingness of the moment and bittersweet inaccessibility of the past—what Diaz describes so well above. It is the preoccupation of literary fiction, I think, as distinct from other forms of storytelling, to seek out permanent and imperishable form for the poignancy of instants that are ever defining our lives and disappearing.

What I try to bear in mind, to keep from surrendering to melancholy and nostalgia, is that the moment as it exists in memory never existed as such in life. The same is true of the moment as it exists in fiction. Nostalgia is a property of recollection, and it may then have less to do with the dearness of the moment itself than with the impossibility of inhabiting it, living it, as it passes. In this sense only in literature does the experience truly, fully, take place.

During your MFA program at the University of Virginia, you were a student of Ann Beattie. How was it like learning from the short story master? How much did she influence you?

It’s very hard to teach someone how to write. In my experience, the best a teacher can do is draw attention to a few bad habits and pass along one or two profound truths that you won’t even understand until you stumble on their concrete form in your own work. This was true of my time with Ann, who never liked my work much, and whom I sought out to work with for this very reason. I thought there must be something to learn here. Her work was so good, and mine was so bad, and yet I couldn’t say, on the sentence level, what accounted for so vast a difference on the story level.

Can I say now? No. Not really. It’s one of the things that makes literature endlessly fascinating: there is a magic in how the best writers write that proves impossible to understand or reproduce, that rebuffs scrutiny, no matter how intently you study it. Ann’s work has a genius that I don’t think anyone has quite penetrated. It’s utterly unique. I wish more of this had rubbed off on me, but it takes a visionary to write, as she does, stories of such power whose grace, brilliance, and perfection are not reducible to, or locatable in, the sentences treated one by one.

Ann always told me two things. First she would say, Why not one more word? The implication was that you always could say more, so why did you stop when you did? If you were me at the time, the deeper implication was that I probably should have stopped long before I did. The second thing she would say was, Let some of the story happen in the reader’s head. I wanted to write everything out, and that meant writing the reader’s imagination right out of the story. So those were the nuggets of wisdom I got from Ann, and that I wasn’t a very good writer.

Who were your imaginary mentors? And who from that list would you still like to meet?

This is a hard question. There are so many! And so many of those I might have hoped to meet died before their time: David Foster Wallace, W. G. Sebald, Roberto Bolaño. Ann Beattie and Deborah Eisenberg, both teachers of mine, influenced me a ton, but they are real, not imaginary, mentors. Grace Paley’s work has had a significant impact on me, as has Donald Barthelme’s. Saul Bellow’s novels affected me a lot right around the time I was developing the ambition to write, but I got to meet him once, so he doesn’t count. Conrad, Joyce, and Woolf blow me away, consistently, but to suggest I learned anything from them is grandiose. Gregor von Rezzori. Borges. Gombrowicz, Emily Brontë, Dorothy Baker, E. L. Doctorow . . . This is all rather unseemly: I signed on to study with them, they accepted zero responsibility for me. Of the writers I still could meet it would thrill me to sit down with Alice Munro, Don DeLillo, Rachel Cusk, or Elena Ferrante. If they read Pif and want to get together, I am easy to track down . . .

I am very curious about your sentences that I find superb but also very effortless. Do you write them down as thoughts or do you focus on the language during revision?

That’s kind of you to say. I should admit that I once fetishized the sentence a lot more than I do today. I have come to think of sentence-writing a bit like a drug habit—something you can safely indulge only a little, every so often. The problem is that if an ambitious sentence isn’t perfect, it is going to do more harm than good; and even if it is perfect, it may not be perfect for the surrounding style.

Over time I’ve tried to get myself to think more about paragraphs than sentences. Getting sentences to work together, attending to the rhythms between them and the fluidity of their ideas, seems to me the greater and more consequential challenge. Style lives as much in the unseen shadows of what sits between sentences, what is left out, as in the serpentine course of the sentence itself.

But the truth is we save our greatest disdain for our most sentimental attachments. I so admire the work of writers like Ann who, as I say above, write the most arresting and profound stories without a single sentence needing to show off. Nonetheless, I cling to what my friend Thomas Pierce calls “razzle-dazzle,” no doubt for fear of what would remain if I did not. I do not know that there is any clear or satisfactory answer to the question of process. I mostly limit myself to sentences and thoughts that originate in the writing of the story itself: extraneous passages and bon mots seem grafted on when patched in. But I do revise intensely and obsessively, far more than I would have had the patience for, starting out. Stories routinely go through several dozen top-to-bottom revisions, and each sentence may then pass through twenty or thirty iterations only to return to its very first phrasing. Meanwhile, I may have changed “the” to “a” and back again more times than sanity recommends.

I noticed that the first few stories in your collection are more or less obedient to the form, whereas the later ones are more experimental, freer… Do you think the time has come for writers to challenge the form and limitations of a short story?

There is an intentional progression in Prodigals from more traditional to more experimental stories. This does not reflect the order in which I wrote the stories, but in a sense, they are meant to arrive at the impasse evoked in the final story’s title, “Metanarrative Breakdown.” The work—on closer inspection, probably, than anyone in her right mind would care to make—does not simply diverge ever further from form, but tends to become more formally adventurous precisely around the question of storytelling and its conventions: What do we make of the artificiality of fiction’s conceits? Do these reflect an arbitrary inheritance or do they suggest a deeper order, a “metanarrative,” that sits behind literature itself and our very storytelling impulse?

Writers have of course been challenging the form and limitations of the short story for a century or two at least. I doubt we are going to have another writer who reinvents the form as many times, with as much innovative success, as Donald Barthelme, whose heyday was the ’60s and ’70s. Borges made the short story something entirely his own. So did Kafka. Chekov’s stories are so contemporary they might have been written last year, and Alice Munro’s so traditional they might have been written a century ago. What’s remarkable about our current moment is that we see the most traditionally great and the most boundary-pushing stories being written and appreciated by the same culture, at the same time.

That said, I do think our taste for the experimental and avant-garde has diminished since the high periods of modernism and postmodernism. This is a shame. Are readers willing to put in less effort, or do editors think readers are willing to put in less effort? Or is it simply that the business has changed, that it has become more of a business, that is, and less concerned with the purity and evolution of the art form itself—profit be damned!

Can you describe a day in a life of a full-time writer?

I can, but honestly, is there anyone who wants to hear about it?

I try to write from when I get up until when I go to sleep. Several things intrude on this ambition: the mailman, hunger, my partner (other people, in general), taxes, sunshine, email, the occasional need to bathe, cabin fever (usually alleviated by a miserable run), tooth-brushing, and . . . um, interviews.

Do you think your readers will expect a Greg Jackson novel sometime soon?

Yes. I hope so. My editors hope so.

Where would you live if not in Brooklyn?

If I could live anywhere? Or realistically speaking? Anywhere: Rome, Mexico City, Berlin, an island someplace (Greece, Sweden, Indonesia), Morocco, southern Spain, Buenos Aires, Hawaii . . . Realistically (and Brooklyn, mind you, is not realistic at all, it’s far too expensive): Maine (where I’m originally from), the Hudson Valley, Los Angeles, Charlottesville or Austin (both places I’ve lived and found distressingly pleasant), anywhere where I have work to do and a quiet space to do it in. I’m not that picky, a bit restless. Brooklyn is a failure of imagination on my part more than anything else.