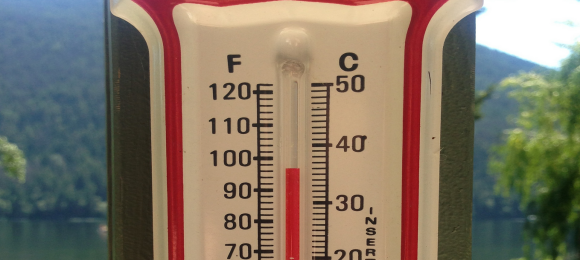

We hadn’t seen Jake and Wendy in over two years, since our engagement party at the Gooney Bird. It was one hundred and thirteen degrees that day. Crippling heat for Northern California.

They sat alone on the far side of the beer garden, under a dying willow tree that offered more shade than the restaurant’s umbrellas. She was a vision of discomfort. He stayed at her side, fanning her with a menu, tearing up paper napkins with his free hand, looking as miserable as his pregnant, nineteen year old girlfriend.

It wasn’t the Jake I knew. No mingling with old friends. No cracking jokes about the ominous symbolism of our flowers wilting in the sun. No coaxing the parents into drinking tequila. Him and Wendy stuck to themselves and left without saying goodbye to anyone.

It came as a hurtful shock when he called to say they wouldn’t be at our wedding a year later – he was supposed to be a groomsman. It was too far and too expensive to go for the night with a toddler, he explained. I didn’t even know they’d moved to her folks’ house in Yuba City after Samson was born. He’d deleted his Facebook profile and hardly ever replied to texts or phone calls.

*

Tracey, my wife, told me to bury my hard feelings when they agreed to come over for dinner. “Lennard, we don’t know how tough having children can be. Just be happy your friend’s in town for your thirtieth birthday.”

Tracey didn’t know Wendy, but she’s always loved Jacob. She went to a lot of effort that day, making the house child-friendly, and setting up our spare bedroom so that baby could go to sleep early and “leave us grownups to drink wine and catch-up”.

I felt dizzy when she relayed this to me; we are really grown-ups. It sounds stupid to be shocked by something so obvious: I’m married, my hairline is retreating, my waistline is expanding, and my dress-sense gets more practical every year. I dislike my job. I’m as grown-up as anyone gets.

It was hot again. Ninety. Bearable weather for us old farts. We set up two fans, and an ice chest full of cold beer and bottled waters on the patio.

They arrived early. I opened the door to see Wendy holding the baby in front of her face.

“Hey, Uncle Lennard, I’m Sammy! How d’ya do!” she said, imitating a child’s high-pitched voice and waving her kid’s right hand at me.

I froze. Samson looked like Jake. He had my friend’s soft nose and brown eyes. She lowered him back into her arms and hee-hawed at my inability to answer back in a childish voice.

“This must be Samson!” Tracey said, moving past me to get a closer look at the baby. “He’s beautiful!”

I smiled. Tracey took Samson, leaving me to hug Wendy. I wrapped my arms around her and felt the troublesome state of her body; she was scarily thin. You couldn’t tell how bad it was with all the layers she wore, but her shoulders were like exposed coral heads and her arms were completely meatless.

“Lennard!” Jake’s voice sounded deep and hearty, like the old Jake. He was thundering up the driveway.

I didn’t know if it was my friend. He was easily forty pounds heavier and all his hair was gone.

They came with nothing. No booze, no snacks, no hors d’oeuvres. Not even a birthday card. I knew they were hurting for money, so I didn’t say anything or take this personally. We popped a bottle of sparkling wine and took a seat outside. Jake emptied his glass in two sips and asked for more.

Conversation with Jake came easily enough. We picked up where we left off. There was an elephant in the room (their absence at our wedding), but we ignored the beast and focused on more current topics, like my birthday, work (neither of them had jobs) and how expensive things have gotten.

Wendy took the gap here. “You guys don’t even know what expensive is. Have you ever bought diapers and formula?”

Trace politely said no for both of us.

Wendy howled at this and then lunged into a sermon about the mounting costs

of baby products, while Jake nodded and added a helpful ‘Yeah’ occasionally.

I drank and filled our glasses.

“Samson’s an angel and we couldn’t be happier,” Wendy said, in closing. She had him on her lap and held his hands. “I’m going to start a parenting blog.”

“Oh, cool!” Tracey said. “Like, a photo blog?”

“No, more like an advice column. I get about four hundred likes on Facebook every week. People have been asking me to start one.”

It was true. But she probably posted about four hundred pictures every day. They covered Samson crawling, sleeping, eating, messing on himself, messing on furniture, going potty (numbers 1 and 2), bathing, playing with his toys, sucking his thumb and so on. She’s in every shot. No sign of Jake. Just her, staring at her son, baring those soulless green eyes into the child’s visual memory bank.

“Like parenting advice?” Wendy said.

“Yeah, plus some stuff about running a household and saving money. It’s going to be called ‘Wendy’s House’.”

“Don’t you mean ‘Wendy’s House and Baby Tips’?” Jake said.

They got into a debate about the name, theme, and the number of people who asked her to start blogging. This went back and forth until Jake stopped talking, allowing Wendy to wax lyrical about her philosophy on motherhood, life and family.

I lost interest and drank, a lot and quickly.

After Wendy finally took a breath, Tracey got up to fetch chips. I followed her.

Samson was crawling around the patio floor, playing with a reed basket we got as a wedding gift from her aunt. He seemed like a happy child. It was hard to focus on him when his mother’s gaunt wrists and his father’s bulging face kept stealing my attention.

“You guys got plans for the summer?” I asked.

Jake shook his head.

“No, but we were kinda thinking of taking Samson to Tahoe this winter. He should be ready to try skiing by then,” Wendy said.

“Like sledding and playing in the snow?” Tracey asked.

“No, skiing. Samson’s more athletic than most one year olds,” Wendy said.

“I don’t think resorts hire out equipment to toddlers.” Tracey’s polite. She’s from Colorado and grew up skiing. She wasn’t wrong. Besides, it’s plain fucking insanity to suggest putting a toddler on skis.

“I think Samson will manage,” Wendy said, bending down to pick up her boy and clean invisible marks from his cheek.

Tracey didn’t want to start a fight, so she said it might be possible, and let the matter fizzle away, like a wave that laps the shore and retreats back into the ocean.

“I’m serious. Even if we have to buy him skis myself,” Wendy hissed. A flush of red engulfed her cheeks. Maybe it was the heat, the champagne or the monkeys from hell living inside her head that caused it. Nobody was fighting her, but she seemed anxious to defend her point.

Tracey and Wendy were inside getting supper ready, leaving Jake and I to watch Samson on the patio.

“You want to hold him?”

I didn’t. I’m terrified of kids. Tracey and I get asked about having one all the time. There’s no hurry. I need time.

“Just try.” Jake set Samson down beside me. I looked at this poor kid and couldn’t help feeling sorry for him. His parents weren’t happy, not with each other and certainly not with themselves. This was no way to start life. “Can I have another smoke over here?”

I said sure, if he was okay with it.

He moved away from the patio where the smoke wouldn’t get to his kid.

I asked Jake to tell me about life in Yuba City with Wendy’s folks.

He’d just finished the bottle of water and started grinding it with his fingers, bending the plastic and making a terrible sound. He was sweating heavily. Fidgeting.

His eyes filled up with water and he started shaking. “I don’t know what the fuck to do anymore. I hate her so much. There are days when I hate him, too, but not like her. He just cries and cries and cries and can’t help that. But she can help being such a bitch.”

“Is she doing okay? She’s so thin.”

“She doesn’t eat, man. That’s just Adderall and cigarettes.”

“And you? You eating?”

“Fuck man, look at me, man – I’m a blob! Of course I’m eating! Her folks are hillbillies. We have fried chicken four times a week, for Christ’s sakes.”

Wendy and Tracey came back just as I was filling our drinks again. I was hammered in the heat. Jake, too. He wiped his eyes and tried to act cool.

Wendy took one look at him and grunted. “Oh, God, is he crying about our life?” She grabbed his glass away and turned to me. “He does this every time we drink with friends. He’s moaning about my parents, right?”

“You never see friends anymore. I think Jake needs some support,” I said on impulse, immediately rushing to Jake’s side.

“Yes we do. We have friends in Yuba City. We see them often and Jake does this shit every time. Don’t you?”

Jake grabbed the drink back. “Shut-up! Why do you have to be such a bitch?” He grunted back tears and banged his palm against his smooth head.

Then the baby started crying. We all looked back and saw Samson sitting alone on the wicker seat, hot, bothered, with a big shit in his diaper. The smell was rancid; it could walk through walls.

Wendy picked him up and hushed the baby quickly. “I’m sorry about this. I’ll be leaving as soon as I’ve changed him. You coming, Dad?”

Jacob nodded and then walked further into the garden to have a cigarette and compose himself.

*

Once they’d left, Tracey and I polished off the rest of the wine and sat out on our patio long after it got dark. A stray cat on heat was howling for suitors near our house. The night air cooled our sweaty faces.

I looked over my lovely wife. “I love you so much,” I said to her, reaching into her hair.

“Forget about it. We don’t have any condoms,” she said.