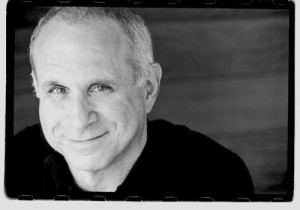

Richard Kramer, an Emmy and multiple Peabody award winning writer, director and producer of numerous television series, is the author of These Things Happen (Unbridled Books, April 15, 2012), his first novel.

The novel, set in Manhattan, centers around two couples — one gay, one straight — and 15-year-old son, Wesley, who lives on the Upper East Side with his mother and stepfather but moves in for a semester with his distant father and his father’s partner, George, who manages a struggling theater district restaurant, in a mid-town brownstone.

Kramer’s film and television credits include thirtysomething, Family, My So-Called Life, and Tales of the City, to name some. His play, Theater District, was staged in 2002 in Chicago, and won a Joseph Jefferson Award.

A graduate of Yale with a BA degree in English. Kramer’s first short story was published in the New Yorker while he was still an undergraduate.

Derek Alger: Your recent novel, These Things Happen, was published to high acclaim.

Richard Kramer: I like that you refer to it as recent. You could also have described it as my ONLY novel. I hope that’s not the case, and that someday I’ll be able to say, “Well, with my FIRST novel, etc., etc., etc. Where, with my fourth . . . ”

And the novel did get some acclaim, although what I’ve found most exciting are the relationships I’ve gotten into with people who HATED it, who chained me to a rock and ate out my liver and posted pictures of that on Amazon or Goodreads, or Facebook. There weren’t many of them, thank God, because reading how talentless you are does hurt, even though you know you can just ignore it, although I don’t know anyone who does. But I have come to love my Haters.

DA: Why’s that?

RK: Maybe because they were so intense that I thought “Well, this is passionate. It’s not bland. The book did something to them.” I sent one hater a message. I thanked him for reading the book, because it takes time to do that, and how much time do any of us have? I told him I valued the intensity of his response — he told me he threw the book into the trash! — because it made me feel I’d achieved something, in a way that’s much richer than when someone comes up to you and says, “I really liked it.” And we got to be friends, in a way, even though he still hates the book! I learned from him, and from some other people, that many readers get pissed off at you if you haven’t written the book they wanted to read. I’d experienced that feeling as a reader, and now I knew how it felt to experience it as an author. I would get asked, “Why did you do it that way, and not this way?” And I saw — my haters helped me see — that I’d never even thought of doing it the way they wished I’d done it. Writing a book, I saw, is pretty much a story of abandon — of just doing something, without thinking, strange as that may sound — which is what’s wonderful about it and what’s scary, too. Trust me, I never wrote a script with a feeling of abandon. You can’t, you’ve promised too many people too many things before you even start.

I followed the best advice I’d gotten about writing, ever, which was from Ed Zwick, on thirtysomething, who said, Just write. Don’t think. It has saved me a hundred times, which is one reason why I dedicated the book to him.

DA: You discovered an interesting concept while writing the novel.

RK: There have been many, but if I had to pick one, it would be the concept of invisibility. How for hundreds of reasons we make others invisible, and ourselves, too. George, the main character in These Things Happen, understands that in his bones, although he’s only able to see it and name it when the forces of the story cause him to.

I wanted to write about a profound person who doesn’t see himself as one. Who thinks he’s a lightweight, trivial, a chorus-boy who barely made it through high school, which is a very limited description of who George is. He’s embedded in a world of fancy-pants folks who think highly of themselves and not so highly of him. I know plenty of profound people, but believe me — they know it. George doesn’t. And I wanted him to to see how the world works in ways the others can’t.

I wanted what George sees to become valuable for Wesley, as he’s in the process of trying to figure out what the world is, who he might want to be in it, what kind of man he’d like to become. George helps him with that, not even knowing he’s doing it. And Wesley loves him for it. And will remember him, and be grateful to him, all his life.

DA: Was the character George based on someone you knew?

RK: Yes. Well — no sorry. It was more like he was based on a realization I had about a real person, who never knew I had it. A real person whom, I guess, I never really knew. And it was more about myself than about him, really, because authors are most interested in themselves, in the end. That’s the arrogance of authorship, the ability to find yourself endlessly fascinating. But as for the real person, the one about whom I had the realization . . .

During the thirtysomething years — on the show, not in my life, although they coincided — I’d be wiped out at the end of the day. TV shows are all adrenaline, all the time. You need to be young, you need a chest that can hold two hearts; a TV show is no country for old men. At night, as I drove home over Laurel Canyon, I got into the habit of going to the same restaurant, and having the same supper each time.

DA: I hope you enjoyed it.

RK: It was a ginger ale, a glass of wine, spaghetti with garlic and oil; sorbet. I sat in a corner beneath a framed photo of the Ponte Vecchio in Florence. Is that where it is? And the same guy staged all this for me every night. He never asked a question. He just led me back, got the whole thing started. I never had to make a reservation. I just walked in, and it was what it was.

A few years into this I wanted a little more of something and I realized I didn’t know his name. Oh, maybe I did, once, but I’d forgotten it. He was Handsome Ageless Blazer’d Gay Guy. That was his name. Seeing this that night, realizing how I’d made him, for most purposes, invisible, I felt stunned and ashamed. It was so easy. I’d denied him specificity, biography, fullness, because — well, because he didn’t seem that important to me. Only what he could do for me seemed important. This wasn’t something I felt good about. Then, twenty years later, when I wasn’t looking for it, the feelings I’d had around that night’s realization came back and took the shape of George in These Things Happen. Because that was his name. I asked, he told me, and when I confessed what I’d done, he explained that no one knew his name, that it was his job to know the names of others. I’d love to find him, give him the book. But why? To show him he had a story, after all. He knew he had a story. He didn’t need me to tell him that.

DA: You’re a true New Yorker.

RK: Always. I always will be. I was born there, although you can be born in Shanghai and still be a New Yorker if that’s what you are inside. The city is a hometown for so many people, forever, because so many people feel it’s where their real lives begin. New York is generous that way.

DA: Yet, you live in LA.

RK: California! I never say LA because if I do then maybe I have to admit I actually live there. After all, it’s only been thirty-seven years. I’m still getting my bearings! I think about moving back to New York all the time but I never quite do. Maybe someday, although I’m not at the age where I see that the barrel of Maybe Someday’s may not be bottomless. So I guess I should say — maybe someday soon. Very soon.

DA: Reading These Things Happen, one would think you lived in New York all your life.

RK: When I was writing it, when I didn’t know if I’d even finish it, I went to live in Brooklyn for four months. I found these two tiny, strange apartments on Craigslist, which were actually wonderful, although one of them was the place of this young guy whom I don’t think had ever cleaned it once. Not once. Never. In his life. But it was perfect, in a way, because he was a young writer — a good one — and when I lived there I felt like I was a young writer, too.

You could reach behind a couch, and pull out a dust ball the size of a child. But it was perfect for me and I think it helped the book. I needed to know how it would feel to be living in the city, and not visiting it, not seeing nine old friends a day, and going to forty-six plays, and a hundred museums. And even with that time on Bedford Avenue in Williamsbridge, which is pretty far from where the book is actually set, I was surprised when people felt I caught New York as it is now. Because I don’t think I wrote about that. Not really.

DA: What did you think you were writing about?

RK: My fantasy. A mash-up. Stuff I remember from when I was a kid. Old New Yorker covers from the 50’s and 60’s. Rodgers and Hart songs. Times Square before Disney, when it was just dirty book stores, and all men wore hats. The strange “sophisticated” vowels of someone like Arlene Francis on What’s My Line, the sound of the “sophisticated” way she laughed, which was of course completely false, but I didn’t know that. The shape of old taxis. The view down Park Avenue, when it’s deserted, in the rain, and the doormen are out, under umbrellas.

And it’s eternal, too, I think. A big city needs an idea of itself, one that everyone agrees on. New York has one. Chicago, certainly. Boston. San Francisco. I don’t think LA has one, which is one of many things I find weird and boring about it. It strikes me as a sort of laziness. In New York, though, there are plenty of people who hold the same New York in their minds that I do in mine. And one of them is my aunt, the pianist Barbara Carroll, who has been a New York institution for more than half a century, a keeper of the flame of the Great American Songbook. I probably should have included her in my acknowledgements; I’m sure all the characters in These Things Happen are big fans of hers.

DA: Your novel sounds like a personal milestone that needed to be written.

RK: In some ways, I think I had to. Also to get it out of the way, so I could write a second book that has nothing to do with New York — which is what I’m doing.

But the New York thing is — I know how to stand on the street there. Who I am in relation to buildings, to buses, to subways. I have a sense of my size, in a way I’ve never had in Los Angeles, where you don’t stand on streets; you search them for parking spots, which may be an unfair thing to say, but I don’t fucking care!

DA: Did you grow up right in the city?

RK: I like to pretend that I did. But I didn’t. I grew up in a little town about thirty miles away via the Long Island Rail Road. I always envied city kids, who grew up in apartment buildings, who took elevators, to their front doors. And now I’ve put some of them in my book. These Things Happen isn’t a YA novel, although it has two young adults — best friends, Wesley and Theo, who are each, for the other, the only one in the world who doesn’t bore them — who are very important to all the YA’s that surround them. God, I hate that descriptor. It’s just targeting, nothing more, which isn’t the world’s most original observation. When I was growing up, I remember there were good books, and bad books. Period. I remember how exciting it was to read a book you didn’t fully understand. It was like a ladder that led to somewhere.

DA: What books come to mind?

RK: One was The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. The Carpetbaggers by Harold Robbins; I was on a panel with his widow, and told her this. The Source by James Michener. You could dip into one of these and think “Someday I’ll know everything they’re talking about in this.” You could aspire to it.

DA: Your book, at some two hundred and fifty pages, is a breeze compared to the ones you just mentioned.

RK: I wanted it to be. I wanted it to hold the reader captive, in a chair; I wanted the reader not to be able to turn away, and almost not to realize that the action, which will change the lives of everyone involved, forever, all spreads out over a mere thirty-six hours. In fact, I wound up taking a lot of stuff that slowed down the fast train. My favorite thing to hear about the book from someone is to have them tell me they read it in one sitting.

DA: During college you received true exposure to the writing world.

RK: More the reading world, really, at least for the first three years. The most important thing that happened to me at Yale was they taught me how to read, that reading was an active pursuit, and that’s never let me down, ever, as a skill for life. It’s up there with knowing how to sew on a button, or change a tire, or unclog a drain. It’s a skill that makes you think you can handle anything.

When I was there, most of the great intellectual figures of the post-war period were all very active and teaching undergraduates; the stars weren’t kept behind glasses then. I had professors I had no business having but what did I know about that?

My favorite was Cleanth Brooks, who was a key member of a group called the New Critics. They’d developed this practice, which was very influential, called close reading, with which you’d consider how a work of literature could be seen as a self-contained, self-referential aesthetic object. It’s much more fun than I make it sound. Believe me. And I’m amazed I remember that description of it; it must have made a big impact on me, because all that is a long time ago.

DA: What was so special about Cleanth Brooks?

RK: He taught a famous class on Faulkner that I took my freshman year. I recently found a bunch of my old papers for that class. Oh, did I ever want to be taken seriously! And I see how turned on I was by Brooks, and Faulkner, and how free my thinking was. Reading those papers I could see the lecture hall. And how the room was always too hot, or too cold, and that didn’t matter. I remember Professor Brooks not teaching us Absalom, Absalom! but teaching us how to read it.

DA: What about your own writing?

RK: I didn’t think about it until my senior year. And looking back, I know why that was. I was gay. I knew it, I was out, I had a boyfriend. And if I wanted to be a writer, could I write about that? No, not then. I could hardly even talk about it, even though I was out, by which I think I mean that it was not a secret.

And no one was writing about it, about the non-melodramatic day-to-day existence of being gay. That would come, but it hadn’t happened yet. This was the year after the Stonewall riots, although of course we didn’t know at the time it was a year after Stonewall, because you never place yourself in history while history is still happening. There were significant writers who everyone “knew” were gay — Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, Gore Vidal. But they never said they were. At least never in the world, in their public life, though Vidal did at the start of his career when he wrote a “gay” novel, a very good one called The City and the Pillar — and paid a high price for it. The New York Times refused to review him for decades after. One point of the house style of the New York Times — told to me by a gay Yale friend who got a job there right after we graduated — was that the word gay had to be put in quotation marks. “Gay.” Like that. So I was separate, snickered at, diminished. I didn’t have the balls to face that.

DA: When did you start writing fiction?

RK: It was heterosexualized, which sounds like a dry-cleaning method. But that’s what I did. It felt terrible, even though I don’t think I knew how to see that, at the time. But I knew something didn’t feel right. It’s almost impossible to write from a non-authentic place. Lots of people do, of course, but I couldn’t — writing is three times as hard, when you do that. But again, it took me decades to even begin to see this, and how it had affected my life.

DA: You did have early success with a short story being published.

RK: I had a strange thing happen to me in my senior year. I took a fiction writing seminar. I’d never written fiction but I thought I’d give it a try. We had to write one short story for the term but that included having it ripped apart by the other students, and endlessly rewriting it. I think I got a B in that class. I don’t remember. I do remember that no one seemed to like it much. At some point during that year I thought I might want to write for a newspaper, or a magazine.

I stuffed envelopes with examples of my work, papers and stuff I’d written for the Yale Daily News and as an afterthought I threw in the story from class, in sort of a why-the-fuck-not frame of mind. I think I wanted to be Woodward and Bernstein because we all wanted to be them, then. That seemed like a good job. Toppling Presidents. Meeting sources in garages, at night.

Then — literally within the same hour — I got two phone calls in my dorm room. The first was from the literary magazine telling me I had won the Yale Fiction Prize; it turned out that the teacher who had dumped on my story had submitted it for consideration, without my knowing. Then, maybe half an hour later, I got a call from someone who said he was “Mr. Shawn,” from “the magazine.” “Mr. Shawn” turned out to be William Shawn, and the magazine was the New Yorker. He was legendary, had been forever.

DA: What did he want?

RK: I remember how formal he was. He wanted to tell me how very much he regretted that there was no job that he could offer me. He did feel, though, that

I was “a young person to be encouraged” (this from my diary) and that they wanted to know if I would “consider” selling them my story that I had included in my envelope of materials. He would be very distressed if I felt under any obligation to say yes. That’s how he talked to me. Literally.

There’s always a catch; the first 22 are just the warm-ups. When I told him that I’d won the fiction prize and they were going to publish the story in the Yale Lit, he told me they couldn’t publish anything that had appeared anywhere else. This strikes me as total bullshit today — this would have reached a thousand readers, at most — but it seemed like the Law at the time. So I should take a few days to make my choice.

DA: That’s a difficult choice to force a kid to make.

RK: And I was a kid. And what choice could I make? I chose “the magazine.” I wish

I hadn’t. I don’t think it helped me at all. I was told just a few weeks ago, by a friend who’s been at the New Yorker since the early 70’s, that Shawn liked putting people in difficult positions, that he enjoyed my discomfort, and spoke of it, with a kind of glee. How fucked-up was that? And then they rejected my next half-dozen efforts, which is probably what sent me to LA, I think, although nothing is ever that clear-cut.

DA: What advice do you wish you could have given to your younger self?

RK: I’d have said — to me — Relax. Wait. I’d have said live a few years, then see who you are, and what you want. I didn’t have anyone to say that to me, unfortunately. It’s hard to find a mentor when you feel you have to lie. Let me correct that — when you know you do. And maybe I didn’t. But I didn’t know that then. It took me many, many years to learn to feel even a little bit comfortable telling a heterosexual man, “Oh, I’m gay.” And note I say a little bit comfortable. Not comfortable. A little bit. So I guess now I can mentor myself. Retroactively.

And here’s a kicker, about gayness and the New Yorker. I wrote to John Cheever, who was a hero of mine, using my publication in the magazine to get his attention. It worked. He met me for lunch in New York, at the Yale Club. He was closeted, although I didn’t know that. I did know he was an alcoholic, because I could see it. He bragged about the many mistresses he was juggling, and I’m sure I spoke of my “girlfriend.” You always had to let the other guy know, or you did then, that there was nothing worrisome about you. But something valuable came out of that lunch. He said to me, “Why the fuck do you want to write for the New Yorker? Go to Hollywood. That’s what I’d do if I was starting out now.” And, again, things are never so clear-cut. I can’t say that I packed my bags because of what he said, and left the next day. But I didn’t forget what he said either.

DA: You found yourself gaining experience at an interesting job after college.

RK: Yes! I got a job as a singles host on a cruise ship that sailed between New York and Bermuda. It turned out to be just what I needed. I was twenty-two at the time. My duties were pretty simple. I ate with the passengers and taught them how to use Mopeds, to go around the island. At night, I danced with them, and played cards, and Scrabble. I was pretty much a gigolo, I guess, without the sex.

DA: Sounds good to me.

RK: It might have been the best experience I ever had! I loved being at sea. I’ve never understood why the words “at sea” are used to describe someone who’s lost, or in a bad way. I never felt more safe than when I was on the ship, crossing timelines. I lost an hour, and regained it; lost it, regained it. I remember thinking that if I kept doing that I would never get old. Maybe, if I’ve ever had another life, maybe I was a starfish, or the gold tooth in a shark’s mouth.

DA: What were the passengers like?

RK: They weren’t fancy; this wasn’t the QE2. I think it cost them three hundred dollars, or close to that, for a week. Most of them had never been anywhere before so this was a true adventure for them. And a lot of them had terminal illnesses, which the cruise line never told me; I just figured it out. The thing was — I felt necessary, and needed. I could see it in their eyes. In Hollywood, you break your ass to please people who don’t need you, to whom you’re nothing, just a name on a long list.

It wasn’t like that at all on the SS Doric. I remember a lot of it, forty years later. Once I had three women, middle-aged cousins, all named Anna for their Czech grandmother. I ate with them one night — I’d change tables as each new course appeared — and one of the Annas said to me, “You know, I am the one who is the beauty cousin, and everyone agrees.”

I remember how a ten dollar tip at the end of the week felt like a thank-you note for all that I’d done. Again, in Hollywood — that doesn’t happen. There’s no connection between what you get and what you’re given. And I know, I know, I make LA sound like the worst place in the world. It isn’t. It’s just — well, I’ve never known what it is. Maybe a ship that goes to nowhere. Or maybe it’s not.

I also read a lot on the ship. The dusty colonial booskstore where we docked had all of Graham Greene in little Penguin editions, so I read pretty much all of his works, two per voyage. I still have some of those books, and they still have sand in them, because I’d taken them to the beach. It was lonely and romantic, and looking back at it now, I see, “What a life for a writer!” On a ship. Free time. Different people at dinner every night. I’d do it again, in a minute.

DA: You once received some crucial words of wisdom from Pauline Kael.

RK: When I got off the ship, I thought to myself — well, now what? I thought about writing a book, but as I’ve said, what could I write a book about? Then, for a moment or two, I thought it would be fun to become a movie critic. I loved Pauline Kael, and had gotten to know her when I wrote her a letter in high school and she asked me to come to lunch at her apartment. So I asked her what she thought.

DA: About becoming a movie critic?

RK: She said, “Absolutely not.” She was not a word-mincer. She told me that I saw life in scenes — an interesting thing to say — and that I had an ear for how people sounded, and how to make people sound different. I’ve heard that a lot, but she was the first to say it to me. So after another bunch of young-man-in-the-city jobs, I wrote a spec script for the TV series Family, which you’ll remember if you were a certain age. I had seen a few scripts but never written one, and something about that show spoke to me. I figured I had nothing to lose, which is unfortunately an attitude you give up way too soon in life. So I wrote the script, and then found out where to send it by reading Variety. A year later, I got a letter telling me they were buying it! I went out for a few weeks to check out LA, hated everything about it, and that was thirty-seven years ago. Fate, when it finds you, posts a guard at your door. It likes to know where you are.

DA: What are you up to now?

RK: Well, Oprah Winfrey approached me about the book — not putting a nickel down. by the way — and we set the book up as a project at HBO, which means they optioned the rights and paid me to write a script. I wrote three scripts. And it was a total fucking waste of time, and I regret doing it. But in show business you are always Charlie Brown, and that’s how they get you, because each time they imply they won’t pull the football away, and you won’t fall on your ass. But then they do. And you do.

I’m writing a new novel. All I can say is it is set in LA, in Sherman Oaks, which is part of the San Fernando Valley, and it is about someone who is not like me in any way and whom I’m sure I will find, when I finish it, is like me in every way. But I have to write my way up to that shock-of-recognition point, and then write past it. I will say — the guy’s name is Bruce. He’s my age. Stay tuned.