The artwork of Randy Walker is one intricately beautiful experiment. A talented fiber artist keen on exploring both form and function in public and private spheres, Walker re-purposes three-dimensional spaces by encasing them with thread. Color, shape, volume, texture – all combine, to transform the ordinary into extraordinary. Spaces, either pre-existing or constructs of his own, are given new life and meaning. Layer by layer, hour after hour, he works until satisfied and confident in his creation. Both tedious and meticulous, his artwork is an obvious labor of love.

Color Falls

Born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, Walker attended the University of Oregon to accomplish his childhood dream of becoming an architect, but was unsatisfied. He found himself trapped in a rigid environment…far from the intuitive, involved and creative world he desired. Leaving the professional world of architecture was a turning point in his life and he began a new adventure as full-time artist in Minneapolis, MN.

Walker’s creations range in size from a small badminton racket to a giant grain elevator (7′ dia. x 44′-9″). The thread he uses can be extremely delicate or strong and sturdy. Anything is possible in his active exploration of spacial character, stability, and visibility.

Walker always has something in the works, and recently received Forecast Public Art’s first McKnight Mid-Career Project Grant. This grant of $50,000 funded a public art project that will uniquely continue to touch many lives. Partnering with YouthLink of Minneapolis, which coordinates services for homeless youth, Walker collaborated with youth to create a large-scale, constantly evolving public sculpture. While permanent, the sculpture will be continually revised and renewed with temporary elements.

Prepare to be amazed with this artist’s ability to transform ordinary objects into magical spaces of possibility with just a bit of thread (actually, quite a lot…). In this interview you will learn all about Randy Walker, his artwork, his intentions, his inspirations, what’s next, and where you can see more!

Emily Frankoski: Where are you from originally and where do you now reside?

Randy Walker: I was born and raised in the Pacific Northwest. I attended college at the University of Oregon. I now reside in Minneapolis.

EF: How did your relationship with art begin? What is your background in art?

RW: I have always been interested in visual arts, particularly three-dimensional arts. As a child, I drew all the time. I also built things with whatever materials were around. I thought the greatest art form was architecture, and my singular goal was to become an architect.

Color Falls

EF: What led you towards art as a career? Did you always want to be an artist?

RW: Through architecture school and beyond, I continued to draw and build things. I found that once I entered the profession, however, I was not creating in the hands-on way I desired. I seemed to have lost a sense of creative freedom, of unplanned, intuitive discovery. I felt the restrictions of the profession were unnatural to my creative process. At some point, maybe five years after I graduated, I decided to devote a small, regular time each week to creating art. Just finding materials and playing with them to see what would happen. At this point, I had completed all requirements for the architectural registration exam. My artistic explorations were becoming ever more exciting to me, and the path ahead was a mystery. I let my architectural licensing accreditation file lapse, and began the journey.

EF: What would you call your medium and how would you define it to someone who has never heard of it before?

RW: Much of my work employs fibrous materials. I wrap, weave and attach fiber to things. These things might be found objects or spaces. The work seems to straddle art and craft and has been described by others as “string art” or “fiber art”. I call it exploration, transformation. It is inherently related to existing forms.

EF: Why did you choose to work with fiber?

EF: Why did you choose to work with fiber?

RW: Trained as an architect, I was familiar with solid materials like concrete, wood, and steel. When I began experimenting with thread and string, it seemed like the most insubstantial, inconsequential, and formless material. It was a challenge to see what I could make it do.

EF: How did you progress from smaller sculptures to large-scale sculptures? What prompted you to, so to speak, “go big”?

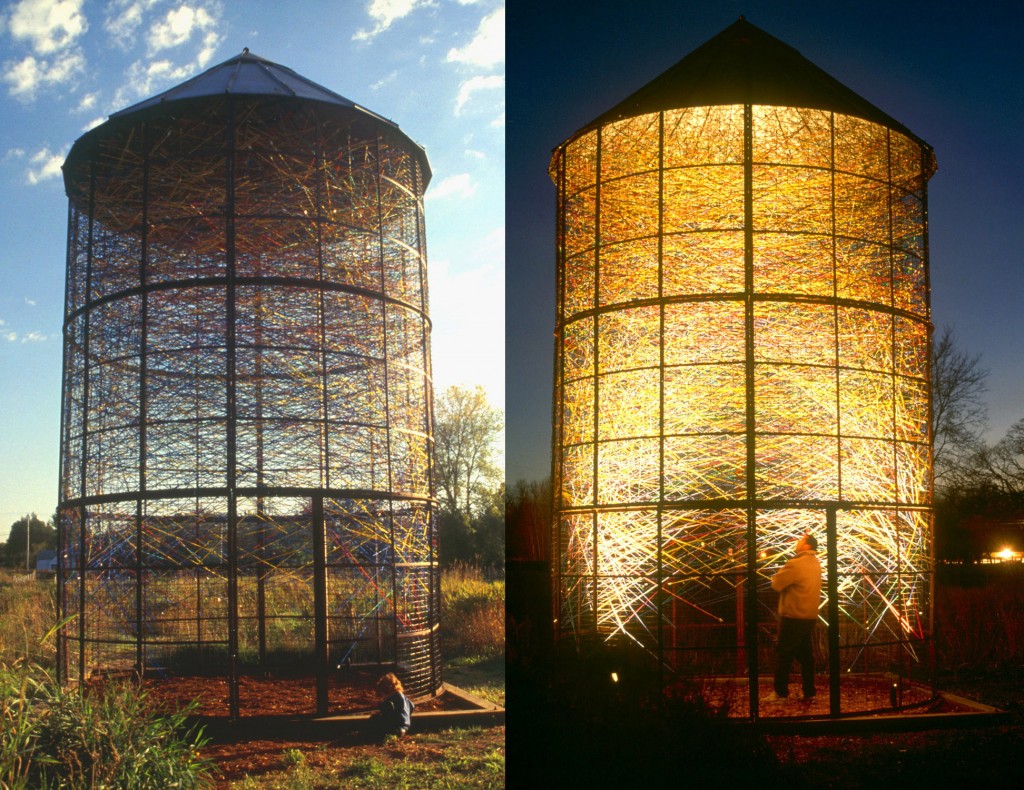

RW: At some point, I began to realize that the objects and spaces I was seeking to transform existed on many scales, not just the small objects with which I had started. The same shapes could be found at architectural scales. The cylindrical volume of a metal-mesh desktop pencil holder, for example, was in principle the same as a twenty-five foot tall steel corncrib. Instead of weaving the pencil holder with sewing thread and needle, I asked myself how and with what I could weave a structure the size of the corncrib. In general, I thought about the possibility of the work becoming something you might experience by entering and moving through. The possibility of using the sun to light the work was also fascinating. It was a natural progression to go bigger, and it opened a world of new challenges.

Dream Elevator (Day & Night)

EF: What inspires your creations? Where do you get your ideas?

RW: My ideas are often inspired by looking closely at the built and natural environment. I try to look at leftover spaces, the voids, and imagine what kinds of structures define them. I wonder how I might fill or weave them. I ask myself how I could do it, what would be required to make it happen, who would witness the process, or even be involved. When I am commissioned for a specific project, I seek a concept that is compatible with the site – its history and scale – and then search hard for meaningful connections.

Dream Elevator (Inside Looking Up)

EF: Walk us through your creative process – from inception to execution.

RW: My process might be summarized in the following form:

- Excitement at winning a commission, receiving a grant, or beginning a new work

- Overwhelmed and inspired at the limitless possibilities to be explored artistically

- Near certainty that there are no possibilities to be explored artistically

- Several ideas of promise emerge; pursuit of these simultaneously

- Indecision about what is appropriate for the particular site or piece

- Commitment to investigating a single idea in depth

- Confidence in chosen path- further conceptual connections made

- Return to Step 2

- Return to Step 3

- Muster confidence to pursue idea boldly, begin design and work

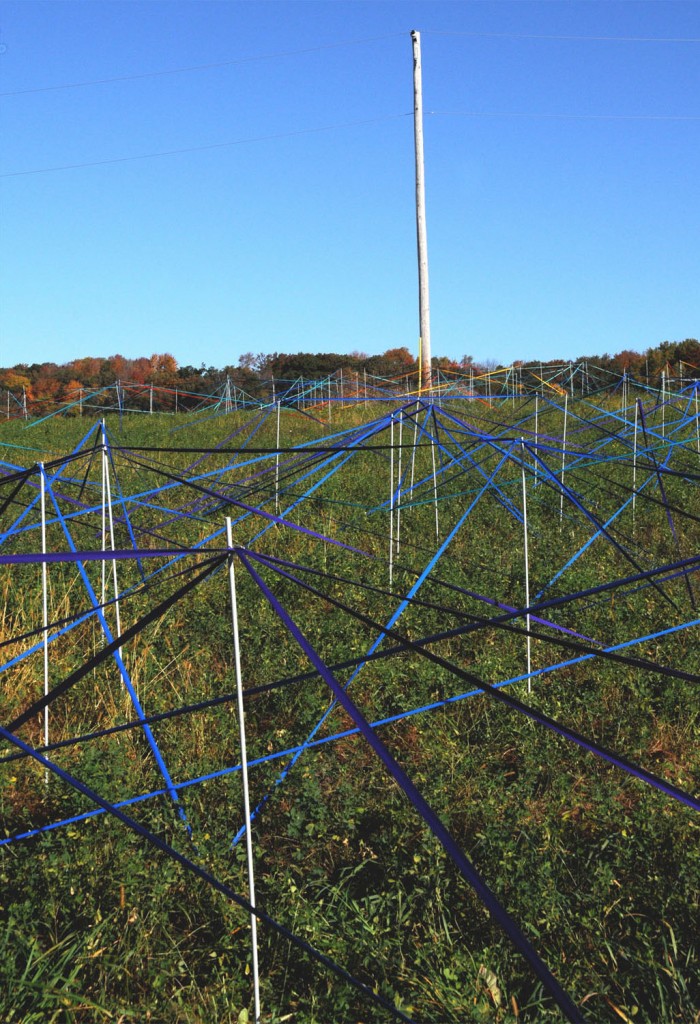

Field Weave

EF: What types of fiber do you use? On your website, you list: nylon, colored acrylic fiber, synthetic rope, etc. – how do you choose which one to use and when/why? Can you explain the differences between them all?

RW: The fiber I choose is based on many factors, including; application (indoor/outdoor); cost; availability; color selection; weight; elasticity; size; strength. Using fiber in outdoor applications is challenging not only because of ultraviolet degradation, but limited color availability. I have spent years researching fibers that might be appropriate for outdoor applications, and if they do not exist in the size I need them, I have had them made custom to my specifications.

EF: Do you find yourself more often picking an already established structure and then creating within the spacial void it contains…or do you more often create the structure from which you then fill with a premeditated creation?

RW: Early on, I felt that it was somehow more “pure” to find an established structure and use its inherent properties with as little alteration as possible. At some point- probably when I could find no satisfactory existing structure- I began to look at forms that had relevance to the project or site. These forms might be found in local history, for instance. I saw no reason why I couldn’t re-create these forms as new frameworks for artistic intervention. This shift in thinking opened up new possibilities and allowed me to engage with a larger range of “found” objects.

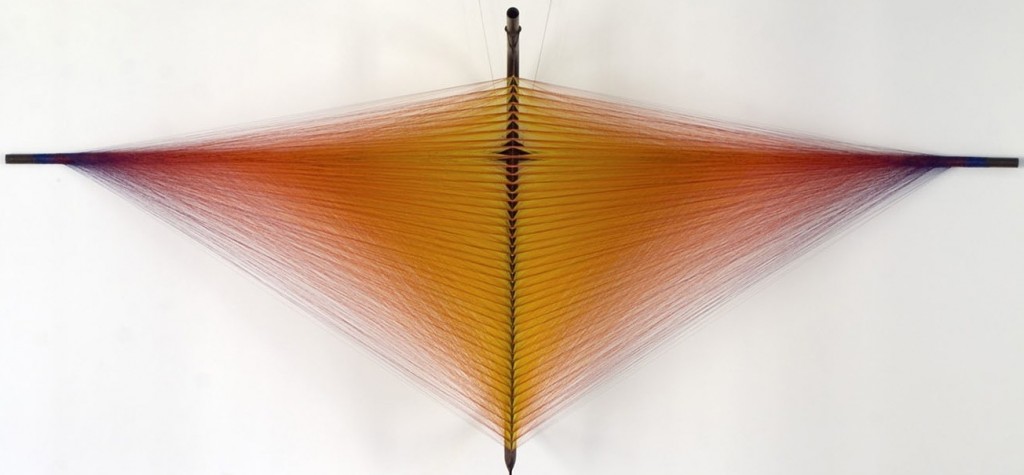

Passage

EF: What do you enjoy most about doing this kind of artwork?

RW: Each project is like beginning again. New challenges keep me at the very edge of my seat, and the outcomes, although thoroughly thought out, are not completely predictable. Each project is a story, a little chapter in my life, which combines into a larger work. I have been fortunate to engage not only new ideas, but meet and work with new people and communities all over the country. There is nothing routine about this. Every day, the landscape shifts and I must figure out the best way to navigate it.

Entanglement

EF: What have you learned about yourself by doing this form of art?

RW: Too much to get into in this limited space! One thing is the value of exploring an artistic idea. Something can be created from nothing if you take it seriously and are observant and flexible. I am always amazed by the fact that, in the creative process, it doesn’t matter where you start- you can start with anything, really- and take it to a very deep place. It’s about shaping, forming, working with it. To produce something meaningful doesn’t happen in an instant.

EF: Creating these delicate webs/nests out of fiber has to get tedious and time consuming. How do you keep yourself focused…and sane? (music? breaks? friends?) – what is it that continues to captivate you while doing this form of art.

RW: The work is tedious, you are correct. I usually have more than one piece in progress concurrently. When I am working on a dense, intricate piece, I usually limit my time to a certain amount of hours on a regular schedule. I know it’s time to stop when things like “What am I doing, anyway?” enter into my head. There is great satisfaction returning to a piece day after day, week after week, to pass a threshold where it becomes visibly clear that the piece was not created in a couple days.

EF: How long does it take to finish something the size of Skimmer? The size of the Woven Corncrib? Discuss how long they take depending on the materials you use and the size of sculpture.

RW: Skimmer took several months of intermittent work. It was done with a very long needle and sewing thread. It was a piece that was created in the studio. I could work in the winter, and I savored the process. Woven Corncrib was created over the course of a summer. It involved a schedule and was a much more regimented process. Often when I am creating an installation somewhere around the country, I have to do my best to guess how long it will take.

EF: How does the public react to your artwork? How would you like them to react?

RW: Generally, I am energized by the public’s response to my work. Because I am often installing on site for an extended period of time, people can see the work evolve and strike up a conversation with me. This familiarizes them with the work, and is much different than a traditional installation where an artwork appears in a couple hours.

Woven Corncrib (Day & Night)

EF: You create for both inside and outside spaces. If you took one of your outside sculptures and brought it inside, would it change in impact or remain the same – and vice versa?

RW: In both indoor and outdoor settings, I am creating work that interacts with the characteristics of a specific site. Scale, color, surrounding architecture, lighting conditions, etc. Some of my smaller, indoor pieces are essentially objects to be viewed in very specific lighting and background. If you took them outside, their color and vibrancy would disappear. On the other hand, a large outdoor piece taken inside would be stripped of its context and appear incomplete.

EF: Are there problems that come up while you are creating outside structures (animals, weather, vandalism, etc.)?

RW: That’s a good start, but there are many more problems than that! What I do is inherently problematic, difficult, paradoxical, and inconvenient. This used to bother me more than it does now. I have embraced these “problems” as part of what makes the work come alive. Each attempt at remedying such difficulties results in a less exciting art. While I do find solutions to the pragmatic restrictions imposed by art in the public realm, I try to not let the art be dampened by them.

Return Journey

EF: What is the lifespan of your pieces? How long do they last? Do you have to replace thread over time for permanent pieces? Does the fiber fade in sunlight or deteriorate?

RW: Lifespan of the pieces varies. Some temporary installations last a matter of weeks or months, while some outdoor installations last over ten years. It depends largely on what parameters I am working within, and what expectations a commissioning agency has for maintenance. I am currently exploring the idea of an art that might be re-created in a new way over time, rather than simply “maintained”. Re-engaging and changing a work seem intrinsic to the work I do with both temporary and permanent materials, and I think there is an opportunity waiting to be explored.

Saw Piece No. 4 (autumn)

EF: If you had to pick one piece to represent yourself as an artist, which would it be and why?

RW: I suppose Woven Corncrib would be one good representative work. It is based on a found, vernacular structure with a beauty that transcends its utilitarian function. It served as the perfect framework for an artistic intervention that retained the original structure while transforming it at the same time.

EF: For whom do you create? Who is your audience?

RW: I create for myself, private collectors, and public commissioning agencies. My audience seems to come from the art world as well as the fine craft world, although I think the work is situated in neither completely. Children are perhaps the most satisfying audience. They are direct, honest, and enthusiastic, and aren’t afraid to say what they really think.

The McKnight Mid-Career Project Grant from Forecast Public Art

Artist working on “Filling the Void”

EF: Tell us a little about The McKnight Mid-Career Project Grant you received in 2012 from Forecast Public Art. What will you be doing for this project and who will it involve?

RW: The Mid-Career Grant is the only opportunity in existence that I’m aware of specifically intended for mid-career public artists. This is an opportunity for an artist to propose a project that pushes the boundaries of his or her practice. I am exploring how a public artwork can bridge the gap between temporary and permanent. My project, entitled Filling the Void (click the link for short video), will involve a permanent structure that will be designed to accommodate future installations. Typically, a public work is either ephemeral or permanent. Permanent works must be maintained, a rather unglamorous and costly chore. Using both permanent and temporary materials as I do, I thought there was potential for a public work to be re-made in a new way rather than merely maintained. To do this, I sought a population that would be motivated to steward such a work into the future. I found Youthlink, an organization in Minneapolis that provides services to youth experiencing homelessness in Minnesota. These youth need a place to claim ownership, a place where they are visible and have freedom to express themselves artistically. They are a continually changing population. The sculpture consists of a steel grid made of metal mesh panels, like a three-dimensional billboard. After I work with youth to complete the initial installation in fiber, new artists and youth will propose different designs in varying media.

Filling The Void (in progress)

EF: What do you hope to inspire in the process and execution of this project?

RW: This project is intended to work at many different levels. It’s generic framework is full of artistic potential, limited only by imagination. At one level, it will act as a beacon for an important building that is very difficult to find. It will also be a very visible, public place for a segment of our population we tend to not see. It will hopefully inspire and challenge other artists, working in other mediums, to find creative ways to engage the structure. It will also be a great experiment, and I hope will set a precedent for public art that is permanent, yet ever-changing with value beyond the accepted notion of permanent public art as static, low-maintenance objects.

Filling The Void (in progress)

EF: What else are you currently working on?

RW: I have just completed a small temporary installation in Jackson, WY. I am beginning a commission for a small public park in Lancaster, PA. I am in design development on a large-scale outdoor commission for the Anderson-Abruzzo International Hot Air Balloon Museum in Albuquerque, NM. Here in Minneapolis, I am working with students and teachers at Roosevelt High School to create an interactive outdoor sculpture. I am also at the initial conceptual stages for a corporate campus in Minnesota.

EF: Do you work alone or with assistance?

RW: Each project is different. For small installations, I prefer to work solo. Large, public work often requires a structural engineer, fabricators, electricians, and riggers. I will often work with several assistants installing a work on site.

EF: Do you collaborate with other artists or the public-at-large often? (do you prefer working alone or with others?)

EF: Do you collaborate with other artists or the public-at-large often? (do you prefer working alone or with others?)

RW: I have collaborated with other artists, and always find it inspiring. Working with the public on a collaborative sculpture has often pushed me to expand my process, as I cannot (and do not want to) control how they will engage a piece.

EF: How do you promote your work? Do you seek out opportunities or do they come to you?

RW: I am always seeking opportunities through appropriate open calls and grants. I am represented by a contemporary textile gallery, and maintain a website.

EF: How do you continue to challenge yourself and grow as an artist?

RW: I create work. When I am actually involved in making work, I see so many possibilities. When I think about making work, I tend to feel more limited. I look for inspiration in unlikely places. Usually it is something unrelated to art that really inspires me. A particular utility pole might suggest a sculpture, for example. Or seeing images of the Large Hadron Collider and trying to fathom what those collisions look like. Other times, the challenges presented by a particular site or commission will force me to find new solutions, pushing my artistic vocabulary into a different realm. I feel that my artistic evolution is at a deeper level than I can ultimately control.

EF: Are the majority of your creations commission-based?

RW: Yes.

EF: Explain the process you go through when you are commissioned to execute a piece. Do you come up with an idea by yourself, or do you share ideas/form ideas with the commissioner?

RW: The majority of commissions require that I develop a concept that has not been determined. Sometimes a commissioning agency has some general concepts that might be explored, but usually you’re on your own. I imagine it’s not unlike writing a story. My process is very non-linear, and the narrative doesn’t necessarily come before the form. If I am developing a concept for a public piece, I usually do not have the commission yet, but am one of several finalists. A committee generally selects the winning proposal.

EF: You create both in urban and rural landscapes. What similarities or differences (if any) do you come across in the end product. Is one a more satisfying canvas for your creations?

EF: You create both in urban and rural landscapes. What similarities or differences (if any) do you come across in the end product. Is one a more satisfying canvas for your creations?

RW: Both urban and rural contexts offer exciting potential for artistic intervention. Both are strewn with found structures and spaces that might serve as the basis for installations. While in an urban setting there will be more people who are exposed to the work, an audience’s level of engagement and responsiveness to the work can be just as lively in a rural setting. I love working on site creating art, whether in the city or out in the country. It’s like I’m an outside observer, not obligated to any of the typical day-to-day activities around me, yet still working away in that environment.

EF: What do you see as the difference between public and private artwork? Do you prefer one over the other?

RW: Private work can be controlled much more easily than public work. The precise physical environment, lighting, etc. Generally, the audience is artistically inclined. With public work, however, the process is inherently more complex, and therefore messier. Even though it is less controlled, working in the public realm is truly exciting. Non-art people, government agencies, logistics, the suspense of what will happen- it’s not always easy or straightforward, but can be tremendously rewarding.

EF: What attracts you to public artwork? What does this medium offer the public?

RW: With public art, you are responding to and making an addition to a complicated set of existing cultural and physical conditions. This makes it possible to transform, highlight, question, beautify, obstruct, or celebrate with art. When a piece of public art is good, it generates discussion, perhaps dissention, and conversation on many different levels.

EF: Do you specialize in any other type of medium?

RW: I don’t really think that I have a specialty medium. I have used fiber to make connections, but it’s really the connections I’m after. There are fiber artists who really know their craft, really know the technical aspects and methods associated with their medium. I’m just making it up, inventing as I go. Any special knowledge I have gained regarding fiber has been necessary to make my connections visible.

Entanglement

EF: Do you sell your artwork? If-so, what is the price-range?

RW: I do sell my work, and the prices can range from several thousand dollars up.

EF: To date, which project has given you most satisfaction?

RW: There are so many that I cannot single any one piece out. Woven Corncrib, Passage, Color Falls, Field Weave, Woven Olla, and Filling the Void: These installations all have their individual histories filled with people, places and times that have become inseparable from the finished works. They have been deeply satisfying and are part of my life journey.

EF: What artists do you admire and why?

EF: What artists do you admire and why?

RW: Christo, Richard Serra, Andy Goldsworthy, Mark Tobey, Naomi and Masakazu Kobayashi, James Turrell, Fred Sandback, Leonore Tawney, Gerhard Richter, Beethoven, the architect Corey Martin, to name a few. I am fascinated by artists who can take a simple theme and explore it to great depths, unearthing treasure most would pass without notice.

EF: Do you have a favorite piece of art (other than your own)?

RW: Hard to say. I’m inspired by any of the above artists.

EF: What is the best piece of advice you have ever received?

RW: You must follow your own path, even if the current conversation has nothing to do with what you are creating. You can keep an ear to the ground, but ultimately you do what you do. Just keep doing it.

EF: What is your favorite book?

RW: Goodnight Moon, by Margaret Wise Brown certainly ranks as one of them. There is just enough text to allow my mind to really be in the Great Green Room, without ruining it with too much description. The way the room gradually darkens so the night sky radiates on the final page is subtle and ingenious. It’s a complete experience of which I never tire.

EF: Where can we see more?

– MN Original – short video about Randy Walker (highly recommended)

– Representation by browngrotta arts

Details for photos included in the interview can be found below:

Color Falls

Robert W. Woodruff Park. Atlanta, GA. Commissioned by the City of Atlanta Office of Cultural Affairs.

2011. Temporary installation. One city block by 15′ tall. Acrylic braid draped over existing waterfall.

Woven Corncrib

Falcon Heights, MN. Funded by a grant from Forecast Public Art.

2004-11. Temporary installation. 13′-6″ dia. x 25′. Synthetic rope, abandoned steel corncrib, illumination.

The piece was re-created on the campus of Western Michigan University from 2009-11.

Photos: Randy Walker (day); Andrea Rugg (night)

Dream Elevator

St. Louis Park, MN. Commissioned by the City of St. Louis Park.

2012. Permanent Installation. 7′ dia. x 44′-9″. Stainless steel, precast concrete, custom-braided polyester, illumination.

The sculpture is based on the world’s first cylindrical concrete grain elevator, built in 1899, and still standing less than a quarter mile from sculpture site.

Photos: Doug Deutscher (day & night); Randy Walker (interior & sign)

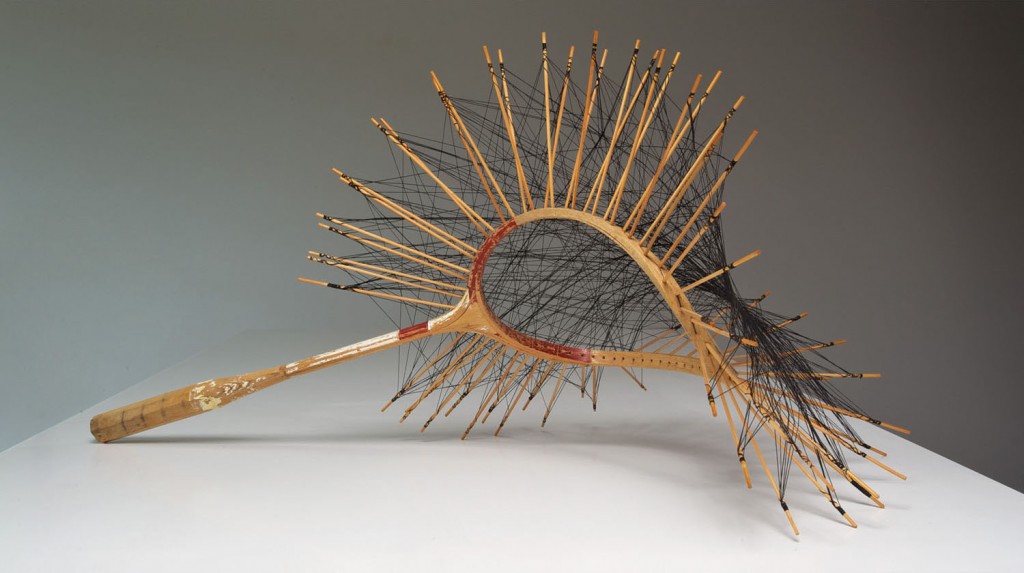

Echoed Surface

Available from Browngrotta Arts

2000. Dimensions variable. Found badminton racquet, bamboo skewers, nylon thread.

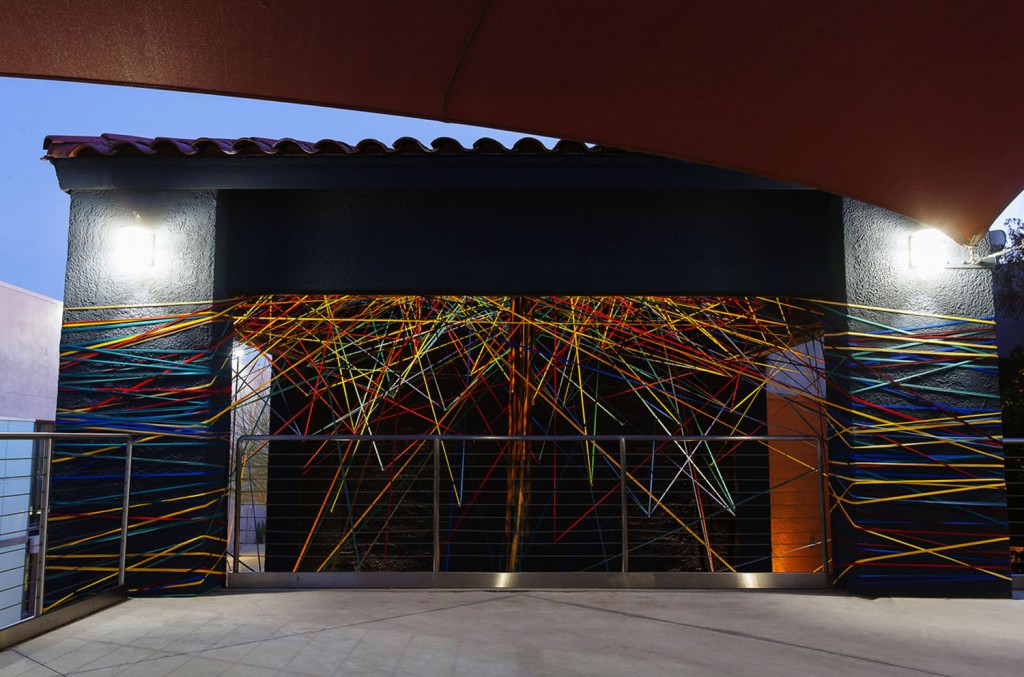

Entanglement

Scottsdale, AZ. Commissioned by Scottsdale Public Art.

2013. Temporary installation. 22’x20’x20′. Acrylic fiber braid, steel eye bolts, illumination.

Photos: Dayvid LeMmon

Field Weave

Reedsburg, WI. Commissioned by the Wormfarm Institute.

2011. Temporary installation. Dimensions variable. Acrylic fiber braid, electric fence posts, sod staples.

Photos: Randy Walker

Passage

Shanaska Creek, MN. Funded by a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board.

2011. Temporary installation. 115’x15’x17′. 136-year-old wrought iron bridge, acrylic fiber braid.

Photos: Randy Walker

Return Journey

Minneapolis, MN. Commissioned by Forecast Public Art.

2010. Permanent Installation. 42’x30’x25′. 1962 rocket play structure, steel, aluminum, landscaping.

Photos: Doug Deutscher

Saw Piece No. 4 (autumn)

Available through Browngrotta Arts.

2005. 96″x40″x30″. Antique saw, steel rod, nylon thread.

Photos: Tom Grotta

Skimmer

Available through Browngrotta Arts.

2003. 72″x20″x12″. Old cheese curd skimmer, nylon thread, steel base.

Photo: Randy Walker

Filling the Void

Minneapolis, MN. Youthlink Youth Opportunity Center. Funded by a grant from the McKnight Foundation and Forecast Public Art.

2013. 20’x3′-9″x14′-4″. Steel, fasteners, landscaping, synthetic fiber, illumination.

Photos: Randy Walker

Portrait of Artist working on Filling the Void

Photo: Julie Swanson