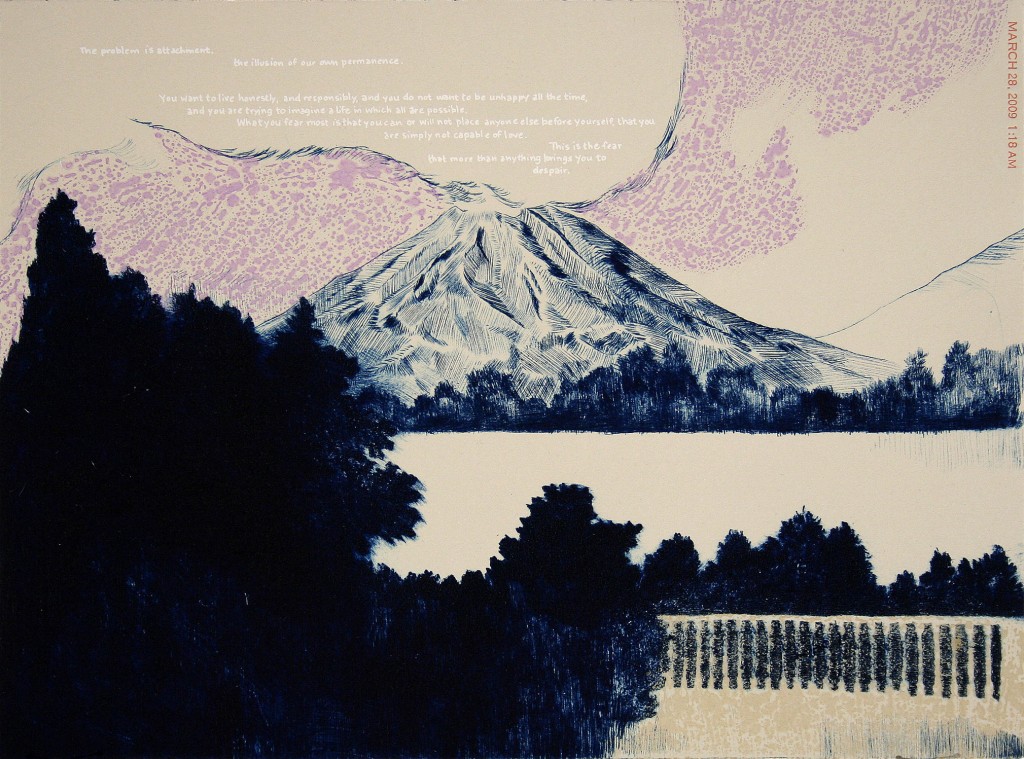

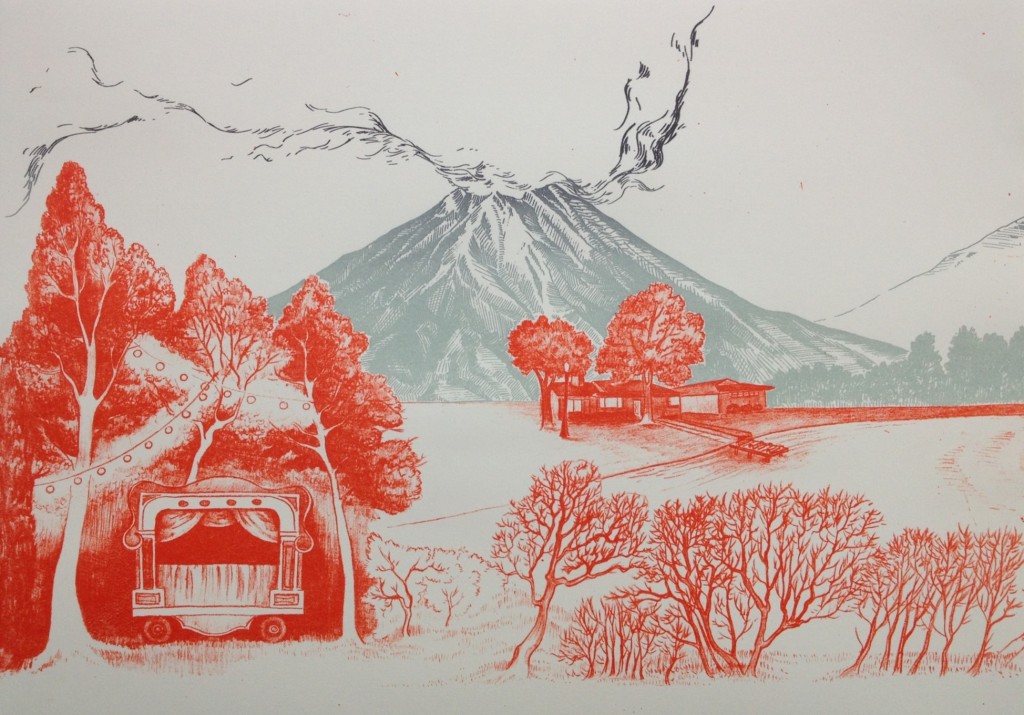

Left side view of Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell

Serena Perrone’s artwork is distinct, focused, eye-catching, and extremely detailed. She seamlessly combines technical printmaking, painting, and drawing to create series upon series of visual story boards, each revealing a little part of who she is, her world view, and what inspires her creations. She possesses the rare ability to interpret with clarity the world she perceives both visually, through her artwork, and with words in writing and conversation. Born in St. Louis, MO, she attended Southern Illinois University (Carbondale) with majors in Painting (BFA), Art History (BA), and French (BA). An MFA in Printmaking from Rhode Island School of Design followed. She currently resides in Philadelphia and continues to focus on her artwork.

I met Serena while she was teaching a printmaking workshop at the Contemporary Art Museum of St. Louis. Serena explained her highly-detailed and time-laden artistic process and execution in a most inclusive manner, even for beginners, like me. To complete the class, Serena led us through a silk-screen printing demo and we each took home a work of our own (executed by us, although actually designed by Serena!). I knew immediately that her work would be a perfect fit for Pif and our readers.

CAM Workshop and Take-Home Print

Serena’s artwork has been included in several group showings as well as solo exhibitions, including Serena Perrone: Volcanoes and Voyages at Cade Tompkins Projects (2011) and A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire at the University of Wyoming, Laramie (2011). Her work is also featured in collections of the Library of Congress; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design; Smith College Museum of Art and The Whitney Museum of American Art as well as many private collections. Serena’s most recent exhibit showcased Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell at the Contemporary Art Museum of Saint Louis, MO (August 2012). Her next solo show is scheduled for Fall 2013 at Swarthmore’s List Gallery.

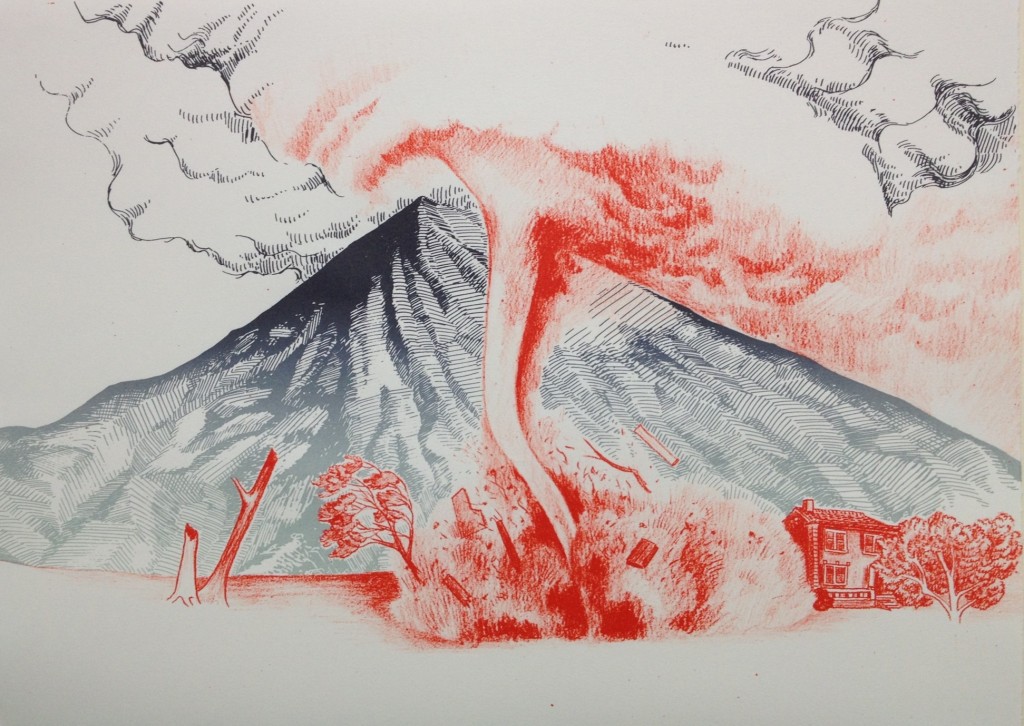

In this interview we focused on two of Serena’s most involved series, A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire, and its companion piece, Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell. The first series was inspired by the late poet Craig Arnold and his lifetime fascination with volcanoes. Perrone created 20 prints of volcanoes, paired with excerpts from his expedition blog. The second series responds to the first, blurring obvious separation of the foreign (like volcanoes) from the familiar experiences of her own life (the important presence of a familiar house). She asks “is it more difficult, daring or noble to fling oneself toward the unfamiliar and dangerous…or hold the dangerously familiar at arm’s length…to learn about oneself and one’s home?” Ultimately, she shares her own point of view while allowing her audience to decide for themselves.

Continue reading to learn more about Serena Perrone, her artistic journey, and the fascination behind both incredibly involved series.

Emily Frankoski: What is your hometown, where do you currently live, and how have these variables impacted your artwork?

Serena Perrone: I was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri and spent most summers in Italy with my Dad’s side of the family. The contrast between urban/suburban St. Louis and the rural coastal mountain village in Sicily had a great impact on me and contributes to the way my aesthetic has developed and the way I make my work. I spent five years in Carbondale, Illinois when I was in college, and moved to Providence, Rhode Island for graduate school. In 2006 I moved to Center City Philadelphia where I still live today.

EF: How long have you been creating artwork and what is your background in art?

EF: How long have you been creating artwork and what is your background in art?

SP: I think most people who are artists as adults can say that they’ve been making art since they were young, so that’s also the case with me. It was always something I did for fun, to pass time, and to daydream. I read and wrote a lot and liked to illustrate what I wrote. I also went through phases where I wanted to be a writer, a detective, an architect, but didn’t really get serious about art until my freshman year of college. I guess I would mark the ‘beginning of being an artist’ as graduating from college in 2003. That’s when I had to implement everything I learned in college, and maintain my studio practice. That’s when I really became more self-directed. It became my lifestyle and not a major or hobby.

In terms of background, all members of my family are involved in the humanities. My mom studied art and became an art teacher. My dad studied political science but ultimately became a professor of Spanish and Italian language and literature. My stepfather is a cinematographer. My half-sister is an architect. My aunts and uncles have been band and orchestra teachers, and my cousins and I all had dual majors in a language and another subject. Everyone in my immediate family speaks at least 3 languages and plays at least two instruments. We are almost all teachers, interested in learning and understanding things, making connections between things. I was fortunate to have traveled so much because I was going between the U.S. and Europe each year, and by the time I had my first art history class in college, I had already seen many of the works we studied in person. For that, I’m forever grateful to my family.

EF: What pulled your towards art as a career? Did you always want to be a print artist?

SP: I started out as an Art and French dual major, and ended up adding a degree in Art History. I got very serious about Art History and Criticism, and ended up taking graduate level courses as an undergrad because I had pretty much taken everything else available. But all of that knowledge had the effect of paralyzing me in the studio a bit – I excelled at writing papers and figure studies, but getting into a zone where I could make original and meaningful, conceptually interesting work sometimes felt difficult under the weight of so much knowledge of art history, contemporary theory, and criticism. I had the hunger and desire to be an artist but was still seeking a clear vision. By the end of college I knew I wanted to go on to an MFA or PhD. That’s when printmaking came into my life. I took an Intro to Printmaking class. Then, remembering how drawn I was to prints like Goya’s, or Cassat’s drypoints and aquatints, I decided to take an etching class. Etching wasn’t as hard a process as I’d heard, and the resulting effects and marks I was able to achieve were really exciting to me. I felt more free to work from imagination, rather than direct observation as I felt compelled to do in painting. I knew far less about printmaking in the canon of art history so copper plate became a clean slate to me and I moved away from painting. It quickly became clear that I should pursue printmaking further and develop my content and voice in that medium, and apply to graduate programs for printmaking, not painting. I was accepted to the San Francisco Art Institute’s Post-Bac Printmaking program, but after a lot of thought, I declined, convinced I could do my own sort of self-directed study. I decided to take a year off and make more print work to build my portfolio for grad school. I spent a summer as an apprentice at Island Press at Washington University in St. Louis; I audited a semester of printmaking at UMSL just so I could have access to acids and presses; I also went to Cortona, Italy for a semester with the University of Georgia as a teaching assistant and studio monitor to gain more experience. I stopped doing as much critical reading and worrying about where I fit in, and spent more time making work. Cortona was a turning point in my studio practice – my prints were improving and I simultaneously went back to oil painting. I was shocked to see that my painting had improved a great deal since I’d moved in to printmaking – somehow printmaking had given me more confidence, skill, and mental space in which to situate myself. I was accepted and started my MFA in Printmaking at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) when I returned from Cortona.

Right side view of Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell

EF: How has your career as an artist progressed since graduating from RISD?

SP: I moved to Philadelphia immediately after graduating from RISD and took a few random jobs. I taught Adjunct for a few semesters. I always had at least two jobs at a time and would be in the studio late nights. I worked on my art no matter if I was in between homes, had a studio or not, had two or three jobs. When I first moved to Philly I was living out of a suitcase with all of my things in storage for several months until I found a place. I remember carving my large woodblocks on the sidewalk outside of the apartment in Washington Square where I was crashing before I had my own place. I was constantly applying to shows, residencies, and opportunities. I also kept a running list of deadlines, because it helped me keep my momentum going. Simultaneously, I began working with Cade Tompkins Projects (a contemporary art dealer – http://www.cadetompkins.com). It has been a true gift and a wonderful partnership. To know that people believe strongly in my work and my future potential gives me the extra fuel I need to press forward even when things are really tough. I’m continually pushing myself to try new things, and have been living an extremely frugal life to be able to support myself with my art as much as possible. I’ve devoted myself to work and traveling for my work, doing residencies, and taking every opportunity to learn new skills beyond what I learned in school. Learning is really important to growth and evolution and the challenges that come with learning are energizing to me.

EF: How do you get your work out there for public viewing?

SP: I started out in college by looking for open calls for exhibitions that seemed thematically of interest to me, or that focused on my medium. I looked for shows that had distinguished jurors or good venues and slowly, after many rounds of applying, I began to get accepted to a few each year. I continued that process through graduate school and beyond. As my resume slowly grew and my work improved, I started to be included in more high-profile shows and I could be more selective. My work has gradually become more widely known, and curators and venues now often invite me to exhibit. In 2006 I applied for a small group show juried by Kara Walker, and was accepted; it was through that exhibition I was seen by Cade Tompkins Projects, which ultimately led to representation. Having representation was a significant step for my work to become more visible to collecting institutions. While I continue to find my own opportunities for exhibitions and collaborations through curators and other artists, my work is simultaneously seen in other venues, exhibited in fairs, and made available to people I would be much less likely to reach on my own. It is a slow and organic process, requiring constant effort and perseverance on both ends, but I really enjoy it.

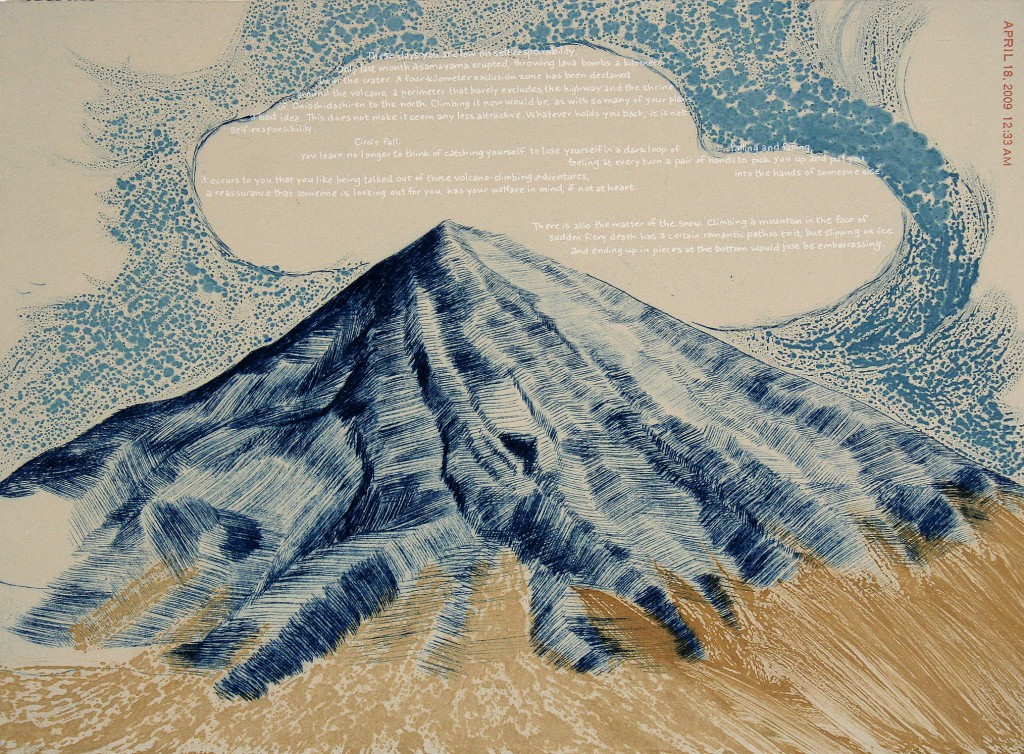

Volcano 7 from A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire (full text located at end of interview)

EF: In which medium did you initially specialize, and has there been a progression?

SP: I started out in painting. I love oil and color and texture, and the way oil can so beautifully describe the human form and the characteristics of light. But once I got into etching I became enamored with the mark and texture it provided. I’ve grown away from oil on canvas and now really prefer to work on paper, whether with printmaking or drawing and painting. Somehow the texture of a soft beautiful printmaking paper and the way the tone of different papers can vibrate with the mediums I use does something for me that canvas doesn’t. The way ink and paper bond together is something I really enjoy.

Etching was my first real love when it comes to printmaking. I really like the way a small etching has the feel of an object – the emboss of the plate, the lines on the paper, and its sense of permanence is very satisfying. Next came woodcut, which allowed me to work large again, as I did in painting. For several years I only did drawing and woodcuts on a large scale. Not only because I liked that physical engagement with the work but also because I didn’t have consistent access to an etching studio. Woodcut is something you can literally do anywhere, and I was spoon-printing by hand and then drawing back into the prints so there was really no limitation on what I could do. I had the privilege to do an etching for Philagrafika with Master Printer Cindi Ettinger in 2008, which was a wonderful experience. In 2010 I picked up moku hanga (Japanese waterbased woodcut) from a collaboration with David Curcio, and I also got to incorporate some letterpress in to my work at All Along Press. Around that time a great facility opened up in Philly (Second State Press) and I became a founding member. They provide community access to intaglio, silkscreen and lithography. I hadn’t done very much work in silkscreen or lithography so when that facility opened I was determined to make good use of everything they had to offer. I’m making a concerted effort to teach myself new skills and combine processes to learn and expand my range. Each new technique presents new exciting possibilities for mark, layering, color, and scale, and opportunity for combining things in new and unexpected ways. I like to challenge myself so I don’t fall into ruts or patterns that become too formulaic. The range of printmaking is so vast and exciting, sometimes it’s hard to even know where to go next.

EF: So, what would you call your current medium and can you walk us through your process?

SP: My overarching medium is printmaking but within that, I would call it mixed processes because a lot of my work employs more than one printmaking process with the inclusion of hand-coloring in the form of drawing or painting. It’s hard for me to explain it in a linear way – it’s often a pretty nebulous process. I have to toss things around for a few weeks until I can see them clearly inside my head. Often I start by writing, and then visualizing a certain type of mark or a certain juxtaposition of marks or colors, or a layering of images, shapes. I may have a vague sense of something I’m looking for, and while I’m trying to get a better view of what that is, I also start working out the imagery and content. I have to take a lot of time to visualize these vague indications of imagery, colors, and marks, or processes and narratives, slowly becoming more polished and defined. I do thumbnail diagrams and notes in my sketchbook to start to nail down a composition, describing what processes and colors to use, and where to start and how to sequence. Then, I’ll refine those diagrams by making the notes more specific, and figure out what materials, papers, and inks to use. Next I begin the work of preparing the plates or doing the preliminary drawings if needed, and before long I’m in the midst of the project. I can spend quite a long time carving blocks, working copper plates, or doing drawings for lithographs or silkscreens. The majority of the time is spent on creating the images. Even though a lot has to be meticulously planned out, there still is always an organic and fluid element to the development and execution of the work. Usually something changes in the plan once I’m significantly into the piece. I’ll drastically change my idea of what the color should be, or what will get layered, included or omitted, or what paper to use. When the plates, blocks, or screens are ready, it’s time to do the printing and editioning. There are a lot of technical aspects, to ensure that images and layered elements all register properly, and that things get printed in the correct order to not disturb the ink of pre-existing layers. Every piece or project has it’s own challenges. It becomes a lot about creative problem solving. The slow nature of the work is crucial though, because it gives me time to ruminate on the content and narrative, and how formal elements relate to them. It’s really thrilling when you start to pull the first good proofs and see on paper what you’ve been visualizing for months.

Panorama view of A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire

EF: Where do you make these elaborate prints? Do you make them in your own studio or a community studio?

SP: I work in various locations depending on the project. Initially I was working out of my apartment after grad school. Eventually I got studios – however, none equipped with printmaking facilities. When Second State Press opened, I became a founding member and fob-holder. I would volunteer 12 hours a week in exchange for 24-hour unlimited press access. That was a great opportunity to make all kinds of new work using everything they offer. I’ve been using Second State Press since then and have been making most of my work there. I used to be more comfortable working alone in my studio, but over the years I’ve really grown accustomed to working in a communal space with others and find I enjoy that a lot. The sense of family and community, the energy and exchange of ideas, and the availability of other people to lend a physical hand when needed is a great advantage. I think that it’s really important for printmakers to travel and do residencies at different shops because each one introduces the influence of new people and new environments into your work.

EF: What inspires your creations/where do you get your ideas for a piece/series?

SP: I’m influenced a lot by my surroundings, and an evolving aesthetic where certain leitmotifs thread throughout the overarching body of work. I look toward literature, poetry, natural landscapes, and built settings, and the way people construct their environments in an attempt to encapsulate or reflect who they think they are or want to become. I’m most often looking inward towards memories, narratives, and fragmentary recollections I wish to expound upon. I use my work as a way to synthesize and digest a lot of what I experience in order to create something physical and real. My work often involves serial imagery and a loose narrative – I tend to think of my work as a vast endeavor, wherein each piece is just a means of communicating one small aspect of an overall image. The larger picture or idea is something that is elusive and always changing, so my work is a constant pursuit, excavation, and examination of that fleeting and intangible thing.

EF: Does color play a distinct role in your artwork?

SP: When I first got into printmaking, I worked more monochromatically. With printmaking, each time you add a color you encounter another layer of difficulty in terms of: creating a separate matrix or plate, expense with each additional plate, issues with registration and added press runs, depending on which technique you employ. Using multiple colors becomes a lot about creative problem solving and requires more forethought and planning. I love color, and when I was painting, my palette was very rich and colorful. Printmaking made my imagery a lot more graphic which was fine for a while but over time I grew to miss color. For the past few years I’ve avoided black, delved into color in my prints, and found it to be very satisfying. Color can add levity to my content and narratives, which is really important. Color can carry implied meaning and I like to employ colors that may be a bit unexpected in light of the imagery or content. Color is exciting, fun, and beautifully seductive. The beautiful thing about printmaking is that even when using black, there is a spectrum of black inks available. I’m not staving off black entirely, but when I do employ it, I want to use it in a more thoughtful, conscious way than when I was starting out. I definitely go through phases with color. At the moment I’m in a very colorful phase.

“A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire”

Volcano 14 from A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire (full text located at end of interview)

EF: Sometimes great literature inspires art and sometimes great art inspires literature. Describe the role literature takes on in your series titled, “A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire”?

SP: In this case, the piece took shape after reading Craig Arnold’s blog posts written in 2009. He called himself the Volcano Pilgrim. He was on a solo expedition in Japan, hiking volcanoes and conducting research for a new collection of poetry to be titled An Exchange for Fire. The blog posts were musings, thoughts, fragments, and observations he recorded and not necessarily his published or formal ‘work.’

EF: Why were you so drawn to this poet and his experience? How did you hear of him?

SP: I have been repeatedly drawn to the image, and suggestive, symbolic nature of the volcano. The time I’ve spent in Italy in close proximity to Etna and Stromboli, the Aeolian Islands, and Vesuvius had an early impact. On a childhood trip to Hawaii, I went hiking on the hot lava floes of Mount Kilauea and saw molten lava flow directly into the ocean, creating incredible billows of steam. Images of volcanoes were commonplace in my home and in Sicilian folk art and culture in general. There is also a great legacy of Japanese printmaking and its depictions of volcanoes, namely Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mt. Fuji, which was also an inspiration for Volcano Pilgrim and Maintaining a Safe Distance. Certain aspects of volcanoes merge into the psyche of cultures centered around them – the volcano is a rich metaphor for various elements of my experience both in Sicily and here in the States. In April of 2009 I heard a news report that an American poet was missing on a volcano in Japan. I didn’t know this poet at the time but the idea that there was someone out there writing poetry about volcanoes was a timely discovery, and exciting to me. I wanted to learn more about him in hopes his poetry could inspire some of my own work. I was also intrigued by the disappearance of this poet and began following the story over subsequent days. Ultimately it was determined that he had fallen to his death in the volcano, and this tragic turn of events was very sobering – this poet was so devoted to his source of inspiration and his work that he risked and lost his life to follow that muse.

EF: In what moment, along this journey of immersion into Arnold’s world, did you decide the creation of a series was needed as a sort of homage to his expedition?

SP: I kept thinking about the volcano as a symbol and started to incorporate it into my work. In July of 2010 while on a residency at the Vermont Studio Center I was creating the series On Escapism and Exile and bought a book of Arnold’s poetry, Made Flesh, and read it straight through. It was powerful and I wanted to read more. That is when I stumbled upon his blog, The Volcano Pilgrim. I read every entry straight through. I was captivated. So many small things stood out as significant to me and dovetailed with the content of my own work – feelings about home and distance, the foreign and familiar and a longing that seemed ever-present. I was very moved by his blog posts, knowing they were written in the days and hours before his death. Lingering on for anyone to read. Knowing his fate, I began to read into some passages that seemed to foreshadow his death in uncanny ways. I decided I had to use his own words and make work in reference to them. When I returned home from Vermont I started to formulate a plan. A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire was created soon after, in September of 2010. It was significant for me to make a work dealing with ambivalence toward home and the familiar in my own home town, where I hadn’t spent much time since moving away in 2003. That month-long immersion in my own childhood home while immersing myself in A Volcano Pilgrim was important for me and my connection to the work.

EF: How did you decide which blog passages to include with each work?

SP: The blog passages I selected for inclusion in each work were not necessarily poems, but fragments of prose that have poetic qualities. Arnold wrote on twenty different days while on his expedition and so I created one piece for each day he wrote. I selected each fragment of text based on its uncanny relationship to my own life and experience, or it’s sense of foreshadowing the author’s untimely death.

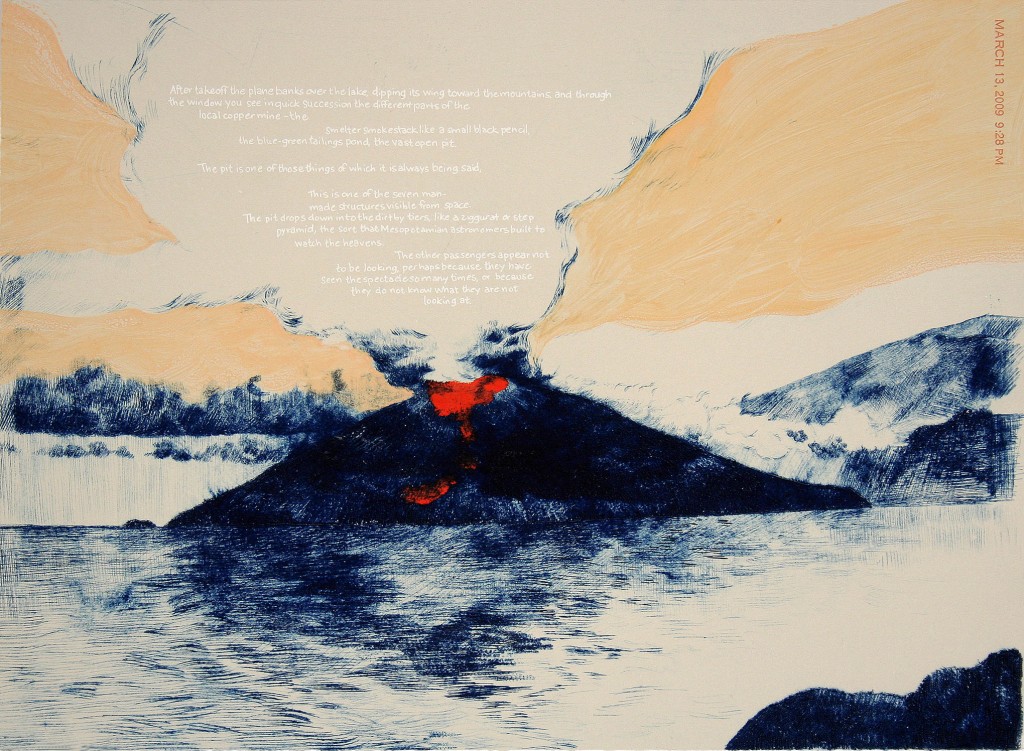

Volcano 1 from A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire (full text located at end of interview)

EF: What mediums did you use in the creation of this series?

SP: I used drypoint for the sake of immediacy and speed, and the ability to work the plates without the use of acids or chemicals. The bright and pastel colors of the gouache monotype were a way to infuse more color into the work and to work as a stylistic contrast to the heavy, dark Prussian Blue of the drypoint marks, and somber aspects of the text. I only had a month in which to create an entire body of work from inception to realization, and a very limited budget, so efficiency was important. Silkscreen was used to incorporate hand-written ‘mechanically’ derived text in a very ephemeral and delicate way. Letterpress served to mimic a digital time-stamp on a blog post or photograph, but is derived from a completely opposite, hand-done process. These seemed to be the best ways to incorporate textual elements with different symbolic and formal qualities.

EF: Of what significance are the dates on each print?

SP: The dates correspond to the actual date and time that each blog entry was posted. Some of the pieces have more than one time stamp because fragments of text on that piece were taken from several different posts that were all generated on a single day. There were certain days when Arnold wrote more than one post. To me the time stamp is important because it denotes chronology. His last posts carry more weight not only because of what they say but also because they are some of his final words.

“Maintaining A Safe Distance and Living to Tell”

Panorama view of Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell

EF: Describe your source of inspiration for and fascination with the familiar and foreign in creating of the series Maintaining A Safe Distance and Living to Tell.

SP: This series came about by reflecting on long-gone chapters of my life that seem like someone else’s reality rather than my own in certain ways. How can something I experienced seem so foreign and distant to my current reality? Thinking so much about home when working on A Volcano Pilgrim, and having the experience of returning to places I used to live, and feeling this sense of melancholy and wonder about those places has provided me with a lot of inspiration for future work. I wonder if everyone feels this way or if it’s distinctly personal. Those complexities are really intriguing to me right now. I see cyclical patterns in the way people grow up, leave home, and then return and seem to re-enact their own life all over again, but this time as adults with children. I see people obsess over their homes, finding the perfect home, or leaving one home for another, in an endless cycle of hope and searching, disappointment, dissatisfaction, longing. I see people pour all of their energies into locating, personalizing, and perfecting their houses. I myself go through cycles of longing for a real home. The next moment I recoil from the thought of such confinement and permanence. In some ways, a ‘home’ as an entire house with all that fills it seems so self-indulgent and extravagant in contrast to the minimal, frugal impermanence of my current mode of living. I think back to memories of all the places I’ve lived and realize that there are many things I don’t remember – did I really live and spend significant time there? Was that really my life for a time? What fateful and significant stories played out in those structures? I felt this urge to really lay it out in front of me, to see this trajectory, to revisit some locations and try to encapsulate in an image what those places evoke for me now.

EF: What mediums did you use in the creation of this series?

SP: I used pencil and pen and ink drawings to create photo lithographs and silkscreens that make up the final piece.

EF: Explain the connection between Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell and A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire. What compelled you to create this “companion piece”?

SP: Many of the themes I was exploring in that series continue to hold my interest and are significant to my understanding of self, how I got here, and where I may go in the future. It was important for me to carry a physical link from A Volcano Pilgrim into the new work. I used all of the same volcanoes, translating them into the new work by redrawing them, turning them into silkscreens rather than drypoints, and using them as backdrops for scenes depicting aspects of my own life. The sense of being split between many places, and the resulting sense of never feeling completely ‘at home’ in any of those places, is something that I’m fast starting to comprehend. My work is a tool in pursuit of the root causes of those feelings.

#14 from Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell

EF: My own personal experience with natural disasters immediately pulled me to Maintaining A Safe Distance and Living to Tell. What do you hope viewers of your work will take away from viewing your art?

SP: The first scene in Maintaining a Safe Distance depicts a specific significant event that coincidentally took place during a very destructive storm that uprooted a tree, crashing it onto my house. Growing up in the Midwest, the threats of tornadoes, wind, lightening, and floods were real and frequent occurrences. Sicily has its own natural destructive forces including landslides, earthquakes, fires, and volcanoes that affect daily life. Our personal lives play out before a backdrop designed by the forces and whims of the natural world. The personal upheavals and emotional states we experience are often not easily seen, but carry the same strength and force as their natural equivalents. Parallels between the external physical world and the internal landscape are easy to draw, and something that interests me. Natural disasters are just another aspect of that external landscape, but the metaphoric imagery they provide can be very apropos.

EF: What are the benefits of showing a series as individual pieces as opposed to a continuously linked panorama? Which presentation do you find more compelling for your audience?

SP: Each series depicts a sequence or chronology, yet conveys narratives somewhat ambiguous in their linear trajectory. I wanted to create images that could stand alone, self-contained, but that would take on even more richness and meaning when displayed end-to-end as one unified whole. When they are not displayed, they are stacked and contained in custom-made clamshell portfolio boxes. To go through the series, one print is seen at a time, lifted, moved aside, for the next one to be held or viewed. This physical movement through the portfolio places it more firmly into the formal and narrative realm of the wordless book, but prints within the portfolio can also venture toward the cinematic realm when displayed in the round as a 25-foot panorama. Each scene is an attempt to paint a specific place or period of time with a broad brush to compartmentalize the time and history of each place, as a way of ‘summing up’ each period. These become like footnotes or flash cards that hint at a fuller narrative. They provide clues for continuing the process at a later date.

EF: Through the execution of these two series, what is your own conclusion? “Is it more difficult, daring or noble to fling oneself towards the unfamiliar and dangerous to learn about oneself and one’s home” or is it “more difficult, daring or noble to do so while remaining close, by holding the dangerously familiar at arm’s length?”

SP: It is indeed difficult and noble to fling oneself toward the unfamiliar and dangerous, as many have done, and as we can see from the life and death of the poet Craig Arnold. To be a constant stranger, to be self-sufficient in that way, and cast off the comforts of home and familiarity are intensely difficult things to do, even for brief periods. In some ways, however, doing that allows for a clearer, more unobstructed view of the things one leaves behind, and of oneself. A high and distant vantage point can make things easier to see in their entirety, but may also blur or soften some of the complexity. Managing to gain an equally clear, unobstructed view from a closer and deeper vantage point can be much more messy and difficult. When you are in the midst of everything you are trying to examine and understand, it can take longer to see the whole, and the path to that clear view can be meandering, confusing, circuitous, full of obstructions and distractions. Maintaining a safe distance means to find that middle-ground from which to view things objectively without losing the sense of intimacy and immediacy. It is like seeing a confluence of rivers and streams from a low-flying plane rather than from the impersonal distance of a satellite, or so closely that one is taken by the swiftly moving current.

#1 from Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell

EF: Some artists seem to hide their techniques in order to create a mystique to their artistic process. On your blog you are very forthcoming, detailing with photos and explanations. Why are you so gracious in sharing your process?

SP: Printmaking is one of those disciplines in which people rely on one another in many ways. Printmakers are indebted to each other. There’s a deep sense of community and collaboration inherent to the process. So much technical knowledge is required most of us could not do what we do without some wonderful guidance and assistance from other printmakers. There is definitely a generational passing-on of technical knowledge. Even the legacy attached to certain presses and shops and the equipment is something printmakers value. Each printer or shop approaches techniques in their own way. Working along side other printmakers is a really valuable opportunity. I’ve found printmakers to be generous and forthcoming with their knowledge and their time. Most printmakers can look at another artists’ work and break it down to figure out what processes were used and in what way – the process can be both mysterious and transparent, but I don’t feel a particular sense of ‘ownership’ over any particular technique. They are all things I’ve learned from other artists and colleagues, and it comes down to how you use those techniques to express your own vision and voice. Passing on the knowledge I’ve gained is one way of reciprocating and showing appreciation and respect for the discipline.

EF: How does art make you feel?

SP: Artmaking is a way of documenting and interpreting what I’m seeing and experiencing in my life, by creating a realm in which disparate elements can come together in a meaningful way. Seeing good art makes me want to get into the studio! Good work is inspiring. The moment I see something I’ve been visualizing finally take shape through the work of my own hands and imagination feels amazing.

EF: If you had to pick one of your pieces to best describe who you are as an artist, which one would it be and why?

SP: At this very moment I would say Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell. It’s my most recent work and culminated in my first solo museum show, which is an important milestone. Each new work strives to touch the core of what I’m experiencing and thinking during the period I’m creating it. Because it is most recent it naturally feels the most relevant. It’s immediate relationship with my current point in life as well as its gaze backwards through my past are important to me and provide a good jumping off point for my next body of work. However, I also feel it’s impossible for one singular work to fully encapsulate who one is as an artist – the context and the evolution of the artist through an entire lifetime of work is greater than any single piece.

#7 from Maintaining a Safe Distance and Living to Tell

EF: How expensive is it to be a print artist?

SP: It’s hard for me to compare it to other disciplines – all can involve a lot of expense depending on how you approach your work, where you live, your scale, the materials you use, and the access you need to certain tools and equipment. I can’t speak for sculpture, ceramics, installation or photography, but in the realm of 2D image-making, I would venture to say that printmaking can be more expensive than drawing or painting. You need access to heavy equipment and chemicals, and those things are difficult to have in a private home or studio for financial, logistical/structural as well as health and safety reasons. Most printmakers opt to rent time and space at a facility already equipped with what they need – this involves membership fees, storage fees, and hourly press-time fees. Many print shops offer bundles of hours or monthly or yearly rates, but printmaking is a very slow and laborious process so hours can add up very quickly. I have been maintaining my own studio space and also volunteering and renting time at printshops to have access to the presses and equipment since my own studio is not equipped for litho, silkscreen, or etching. The materials can be very expensive as well – an average 22×30” sheet of printmaking paper can be 3-6 dollars apiece. If you use copper for etching, the cost is very high. The inks and chemicals probably are equivalent to buying oil or acrylics for a painter. Someone who does traditional painting on canvas may be able to work at home or in a basic studio set-up. The cost of canvas and stretchers, brushes and paint can be less than copper or litho stones, printmaking paper and plates plus press fees. To do printmaking on a tight budget requires you plan ahead and often re-use materials, like using both the front and the back of a copper plate, or re-working them; saving all the scraps of paper from an edition for use on another edition, and being very frugal with ink. It is challenging but printmakers are known for being creative in their ability to re-work and re-use imagery and materials. One benefit of printmaking is the ability to make multiples, which sometimes makes up for the expense involved.

EF: Do you focus on producing series or sometimes create work that stands alone?

SP: I really enjoy serial imagery because of its ability to convey literal or implied narrative, but I do like to intersperse my serial work with singular pieces as well. Some of my singular works include Approach and Descent, Settlements, In Our Cinematic Lives, and Through the Periscope. I like that singular works can provide a good way to branch out into new techniques or new content and experimental ideas. However, I really enjoy the long and involved process of creating a series and fleshing out a theme or visual structure over the course of multiple pieces. I love to see the evolution of an idea through a serial approach.

EF: On average, how long does it take you to finish a piece/series?

SP: It really varies. Maintaining a Safe Distance took nine months from start to finish. Making the copper plates for Approach and Descent took about six months. Printing one of those takes about half a day, and hand-painting the tiny stripes on one print in the edition takes about a week. The four-part series On Escapism and Exile took about a month, because I did it while on a residency at the Vermont Studio Center, so I worked all day every day for an entire month. Likewise, A Volcano Pilgrim in Exchange for Fire took about a month to execute, but it was an extremely intense month where I was doing absolutely nothing else, and working probably 15 hours a day, on average. The seven-part series In the Realm of Reverie took three years to complete (an average block would take 2-4 months to carve, each impression takes a full day to print, and the silverpoint drawing on one print takes up to two weeks). My work is difficult to edition, which is partly why my edition sizes remain small.

EF: What is the best piece of advice you have received?

That’s a tough one – I’ve been in touch with so many wonderful people in my life and I hope I have been implementing what I’ve learned from them. Art-wise it has been to just keep making work, never stop learning, and not be in too much of a hurry. You have to love the process – and enjoy the aspect of uncertainty inherent to being an artist. Patience is something many of us have to learn and work towards, but it makes everything else easier. Be patient, feel gratitude, keep working and enjoy it.

EF: What is your favorite piece of art/artist?

SP: Such a tough question. I love so many – I don’t think it would be fair of me to name a favorite. My tastes change as well. I do always go out of my way to see Pontormo’s Deposition, or Fra Angelico’s frescos in the Convent of San Marco whenever I’m in Florence.

EF: What is your favorite book?

SP: Again, I really can’t pinpoint a single book. I’d have to list a few for a statement like this to feel right. Blow-Up and Other Stories by Julio Cortazar, everything by Haruki Murakami – particularly Kafka on the Shore, Dave Eggers’ You Shall Know Our Velocity, Anne Carson’s An Autobiography of Red, Steven Millhauser’s Dangerous Laughter, The Invention of Morel by Adoflo Bioy Casares, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Strange Pilgrims are among my favorites. Craig Arnold’s Made Flesh and Rebecca Lindenberg’s Love, an Index have been really moving and inspiring. I used to be into long novels but in recent years short stories, essays, and poetry have held my interest more.

EF: What do you plan to do next with your art? Are you working on anything new?

SP: I just finished Maintaining a Safe Distance, which was a 9-month project, and so I’m slowly formulating ideas for my next bodies of work. I’d like to work in litho again, and go back into moku hanga and etching as well. An upcoming project I’m looking forward to will be Due North, curated by Marianne Bernstein, that will hopefully involve travel to Iceland and a subsequent exhibition of works created during and as a result of that experience.

To see more from Serena, visit her website serenaperrone.com or her blog printmepullyou.blogspot.com.

*Inquiries about price and availability can be directed to Cade Tompkins Projects who handles sales of her work.

If you are interested in reading the writing by Craig Arnold included in Serena’s prints, read on below:

Volcano 1:

“Salt Lake City to San Francisco

This entry was posted on March 13, 2009 at 9:28 pm

After takeoff the plane banks over the lake, dipping its wing toward the mountains, and through the window you see in quick succession the different parts of the local copper mine – the smelter smokestack like a small black pencil, the blue-green tailings pond, the vast open pit. The pit is one of those things of which it is always being said, This is one of the seven man-made structures visible from space. Except for the Great Wall of China, you cannot remember the others.

The pit drops down into the dirt by tiers, like a ziggurat or step pyramid, the sort that Mesopotamian astronomers built to watch the heavens. Only this pyramid is made of empty space, and looks down. If you were standing on the rim of the pit you would see crawling up the long spiral a series of house-sized trucks, each of their tires as tall as two men. But from the plane, they are invisible. The other passengers appear not to be looking, perhaps because they have seen the spectacle so many times, or because they do not know what they are not looking at.”

Volcano 7:

“Tokyo, 4

This entry was posted on March 28, 2009 at 1:18 am

At Zojoji Temple you drop a handful of thin coins into the offering box, put a pinch of incense on the brazier, bow, and immediately wish you hadn’t. It is a performance, an American’s affected openness toward a faith you do not belong to and which does not much mind what you think of it.

Around the altar the floor is raised, polished wood, over which priests and worshippers slide to and fro in their socks. It is all gold, gold paint on the Buddha and the altar and the pillars, long gold chandeliers reaching halfway to the ground. You take a seat at the back, sit and rest.

How the eyes water

through a blue haze of incense

the glitter of gold

The problem, Buddhism teaches us, is attachment. We attach ourselves to our desires – for power, for possessions, for other people – to assert our selves, the illusion of our own permanence. The enlightened person understands that such attachments are ephemeral, lets them go.

But looked at another way, the enlightened person is entirely selfish, for among these attachments are responsibilities. To truly overcome the self would be to submit to these responsibilities – this, at least, is what Christ and Confucius seem to teach us.

Some responsibilities are given to you – parents, children, your own survival. Others are chosen. One may chose to have a child, or not. One may chose to have a partner, or not. Might it be better to choose not to take on such responsibilities? Or is that choice simply another form of selfishness?

Perhaps we do not make these choices; we make them without deliberation, or they are made for us, by our history and our circumstances. And perhaps to think this way is also selfish, avoiding the responsibility of making a choice.

You want to live honestly, and responsibly, and you do not want to be unhappy all the time, and you are trying to imagine a life in which all are possible. What you fear most is that you can or will not place anyone else before yourself, that you are simply not capable of love. This is the fear that more than anything brings you to despair.

Zojoji Temple

the scritch-scratch of a twig broom

on a dry flagstone”

Volcano 14:

“Asama-yama, 4

This entry was posted on April 18, 2009 at 12:33 am

These days you are low on self-responsibility. Only last month Asamayama erupted, throwing lava bombs a kilometer from the crater. A four-kilometer exclusion zone has been declared around the volcano, a perimeter that barely excludes the highway and the shrine of Onioshidashi-en to the north. Climbing it now would be, as with so many of your plans, a bad idea. This does not make it seem any less attractive. Whatever holds you back, it is not self-responsibility.

There is a game you would play in drama class called Circle Fall. The cast or company forms a ring, with one of their number in the middle, close enough so that they may reach out and grasp him by the shoulders or under the arms. He stands with feet together, stiff and straight, closes his eyes. Then he gradually lets himself topple, forward or backward or to one side, like a tree the lumberjack has just given a final stroke of the axe.

Now he is in the hands of the others. As he falls, they must catch him, taking the weight of his body gently and gradually, raise him upright again. Then they give him another push, maybe in this direction, maybe in that. He falls, and is caught; he is stood back up, and toppled over again. One might think there would be the one joker in the pack who would let their fellow fall, but no one ever does. It would be more than a betrayal.

At first the temptation is strong to catch your balance, to put one foot out to stop yourself, not yet quite believing that you will be caught. But you learn no longer to think of catching yourself, to lose yourself in a dark loop of falling and falling, feeling at every turn a pair of hands to pick you up and put you into the hands of someone else. And your memories of this game, from your mistrustful teens, are of great comfort. Now, many years later, it occurs to you that you like being talked out of these volcano-climbing adventures, a reassurance that someone is looking out for you, has your welfare in mind, if not at heart.

There is also the matter of the snow. Climbing a mountain in the face of sudden fiery death has a certain romantic pathos to it, but slipping on ice and ending up in pieces at the bottom would just be embarrassing.”