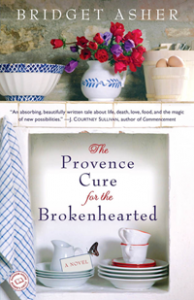

Julianna Baggott, http://www.juliannabaggott.com, who also writes as N.E. Bode and Bridget Asher, is the author of eighteen books, including Which Brings Me To You, co-written with Steve Almond, (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2006) and most recently The Provence Cure For The Broken Heart (Bantam, 2011), written under the pen name Asher.

Baggott earned an MFA at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and her first published novel, Girl Talk (Washington Square Press, 2002), was a national bestseller, quickly followed by her novel, The Miss America Family (Washington Square Press, 2003), and then The Madam (Washington Square Press, 2004), an historical novel based on the life of her grandmother.

She is also a highly claimed poet, who has published three poetry collections, The Country Of Mothers (Crab Orchard Award Series in Poetry, Southern Illinois University Press, 2001), Lizzie Borden In Love: Poems In Women’s Voices (Crab Orchard Award Series in Poetry, Southern Illinois Press, 2006), and Compulsions Of Silk Worms And Bees: Poems (Lena-Mile Weaver Todd Poetry Series Award, Louisiana State University Press, 2007). Her poems have appeared in such publications as Poetry, American Poetry Review, and Best American Poetry.

Baggott’s essays, poems, and stories have appeared in several anthologies, and her work has been published in over a hundred publications, including The New York Times, Glamour, and The Boston Globe, to name a few. She has also read on NPR’s Here And Now and Talk Of The Nation.

She lives in Florida with her husband, writer David D.W. Scott, and their four children, and is an associate professor in the Creative Writing Program at Florida State University. She is also co-founder of Kids in Need – Books in Deed, and has a blog at: www.bridgetasher.blogspot.com.

DA: Let’s start at the beginning, did you start writing at an early age?

JB: I grew up in Delaware, a happy childhood, in point of fact, if childhoods can be happy. I think childhood is often beautifully grotesque even at its happiest. The child’s viewpoint is alarming that way. It was a college town and I grew up holding a grudge against professors, ironic now that I am one. I have a grudge against myself. I was athletic, hyper. My parents took me to tons of plays and traveled a lot. My sister lived in New York City, studying to be an actress, so I got used to the idea that people wrote words on paper. I understood the playwright as more than just conceptual and that’s what I wanted to be. I loved Mamet really young. A hard crush.

DA: You were pretty set on becoming a writer by the time you went to college.

JB: I was. I found out years later that my mother called the head of the department of English to make sure that they wouldn’t ruin my talent. Humiliating fact. I had no idea at the time that she thought I had any talent really. Loyola College (now University) had a creative writing major, which is why I went. But when I arrived, my advisor told me that with this major you had to have another major to prop it up — for practical purposes. I was really pissed. I told the head of the department that the school’s job was to educate me, not make me employable. He asked me if I wanted to work at McDonalds. I told him it was none of his business and that he shouldn’t worry so much over me not being able to give back to the alumni fund one day and just teach me. That was my freshman year. I was a complete and utter pain in the ass. I took French as my second major, which leads me to my current novel, just published, The Provence Cure for the Brokenhearted. Some shit comes full circle.

DA: What came after college?

JB: I taught middle school at a school called the Immaculate Conception. I taught ballroom dance, raked leaves, babysat, taught English to aspiring Spanish pilots. Mainly, I knew that there was a thing called an MFA where you studied nothing but writing. I wanted to do that. So I wrote a lot to prep for that.

DA: And then off to graduate school.

JB: UNC-Greensboro to study with Fred Chappell whom I hold very dear. I got to drown in writing for two years. I loved it. I also met my husband there, a poet. My mother had strictly warned me not to fall in love with a poet, so it was mandatory. We got married right away and have been since — four kids later.

DA: A period of struggle came after graduate school.

JB: We lived way below the poverty level. We ran a boarding house out of a three-bedroom condo actually. We started having kids. It was hard, but good. We worked as a team. Quit the jobs that deserved to be quit and worked really hard for very little pay and learned a lot. Dave’s jobs got better and better and then I sold a novel, then another, and he became a stay at home dad. I wanted to write and have a big family. I couldn’t sacrifice one for the other or I’d be too resentful. So I did both and I married someone who’s a great partner to me in all ways.

DA: Quite impressive, you published your first short story at an early age.

JB: Yes, I published my first short story at 22 and sold my first novel before I was thirty. I started out as a short story writer. After two kids I started writing poems, obsessively, then I moved to novels – for adults at first. But eventually N.E. Bode was born and I wrote The Anybodies Trilogy, which has done well for itself. Bridget Asher has been a joy to write. And I’ve recently sold rights to a trilogy called PURE, and Fox 2000 bought the film rights.

DA: Your novel, The Madam, has some historical roots.

JB: The Madam is based on the life of my grandmother who was raised in a whorehouse, during the Great Depression; her mother was the madam of the house. It was an emotionally grueling novel to write. My grandmother was alive and so I interviewed her for it. Very hard to take. But I’m glad that we did it. In some ways, it’s the best book I’ve ever written – an act of love. But in one way or another, every novel I write feels like an act of love — willful.

DA: You also have published some impressive poetry collections.

JB: Thanks. After my second child was born, I felt fully betrayed by motherhood and I had less time but more explosive things to say. Poetry worked. I read collections of poetry voraciously and was awed by works by Adelia Prada, Marie Howe, Brigit Pegeen Kelly…I needed those voices in my life as well as my work.

DA: Tell us about your first poetry collection.

JB: The Country Of Mothers. The collection is memoiristic in some ways — about being a mother and a daughter. It also draws on faith and religion.

DA: You touch on an impressive array of voices in Lizzie Borden In Love: Poems In Women’s Voices.

JB: Again, thanks. Yes, I range from Mary Todd Lincoln to Monica Lewinsky. I inhabit the inner voice of the speaker in each poem in a particular historic moment. It’s a combination of imagination and history. I try to go deeply with people that we thought we knew but didn’t really. And, too, I was writing about myself without knowing it.

DA: And then you started publishing novels for younger readers.

JB: I’d written three literary novels in three years and my agent suggested getting under a pen name. I was reading the books I first fell in love with to my own kids and so it was a natural progression.

DA: Maybe we should clear up the identity problem of what names you write under. You sound engaging and humorous, but do you have a split personality I missed?

JB: Bode attended the Alton School for the Remarkably Giftless — I am Bode. Asher writes smart funny novels about grief and love and the strange contemporary world we inhabit — I am Asher. And I’m Baggott — I’m always Baggott.

DA: You have a lively brood, perhaps you can offer some thoughts for mothers who write.

JB: Four kids — high school, middle school, elementary and pre-K. For me, intrusion has become part of my creative process. No way around it. Having kids also has mined my soul. Surely something else would have — life on this planet does this to us. But I’m glad it’s these particular miners. One piece of advice to mothers who write, reclaim your muse time. Guard it.

DA: Young sports fans should love your recent book The Prince Of Fenway Park.

JB: Yeah, my husband Dave is a huge Red Sox fan. I couldn’t have written the novel without his help on the research end. I came out as Baggott on this kid novel because it didn’t have Bode’s feverish voice and my editor wanted me to. Basically, there was a curse on the Red Sox. It was reversed, and this is the boy who did it. Over the course of the novel, Oscar Egg meets 12-year-old versions of Jackie Robinson, Ty Cobb, Ted Williams, Willie Mays, and of course, Babe Ruth.

DA: Tell us how Which Brings Me To You came about.

JB: The tagline “A Novel in Confessions” came to me. I thought it’d be cool to write it with a male writer. Steve Almond was my first choice. He said no. I said, “Great. I’ll send you the first chapter.” And the rest is history, as they say. It’s an epistolary novel, letters by John and Jane — dubbed an “extended power-flirt.”

DA: You found a home as a teacher.

JB: I love the classroom. I’ll always feel foreign in the land of academia. I keep a loud classroom. I like the steamrolling conversation. I like the tight focus on craft.

DA: You and your husband co-founded a nonprofit organization Kids In Need – Books In Deed.

JB: Kids in Need – Books in Deed was born out of some real frustrations with the deeply unequal and racially divided system of education that I was witnessing on school visits. It’s a small organization. We do book drives mainly (but also take financial donations) and get books to underprivileged kids throughout the state of Florida. www.booksindeed.org.