On the first weekend of May, I attended Hedgebrook Vortext, a three-day writers’ conference that took place at Whidbey Institute, on Whidbey Island, Washington. Organized by Hedgebrook, a leading organization helping women writers, Vortext is an annual event that celebrates women authoring change. During the conference, I was fortunate to lodge on-site, inside of Whidbey Institute, in a tiny cottage surrounded by tall evergreen trees and narrow trails that branched like sunrays, leading deeper into the forest.

Inside my cottage were two twin beds, two bedside bookshelves, one small sofa with two cushions, a silent wood burner next to which was a basket filled with logs, two identical electric room heaters that welcomed me with heat, and a few wall hooks so that I could hang my clothes. Above my bed was a meditation loft.

My room didn’t have a bathroom. The nearest was probably a hundred meters away, which is a minute-long walk by daylight, and I didn’t mind it. But my concern was whether this trail was walkable in the middle of the night? My mind quickly produced a picture that disturbed me: I’m waking up at three in the morning unable to hold the content of my bladder, and I’m stepping out of the warmth of my cottage and into the dark, dark woods. I remembered that I had removed my daughter’s porta-potty from my trunk a few months ago, and I wished I hadn’t. I scanned the room in search of an object I could use in case of an emergency, in case I’m too afraid to walk to the bathroom at three in the morning. (I don’t know why the number three was on my mind, but it was there, and it twinkled like the words “new post” or “link in bio” that I see every day on Instagram). A ladder rose from the floor like a vine leading to the meditation loft. It was made of branches put together, so it looked like an actual tree spiraling upward toward the ceiling. My mind still processed the number three. Three in the morning. A tree rose from the floor and spiraled upward.

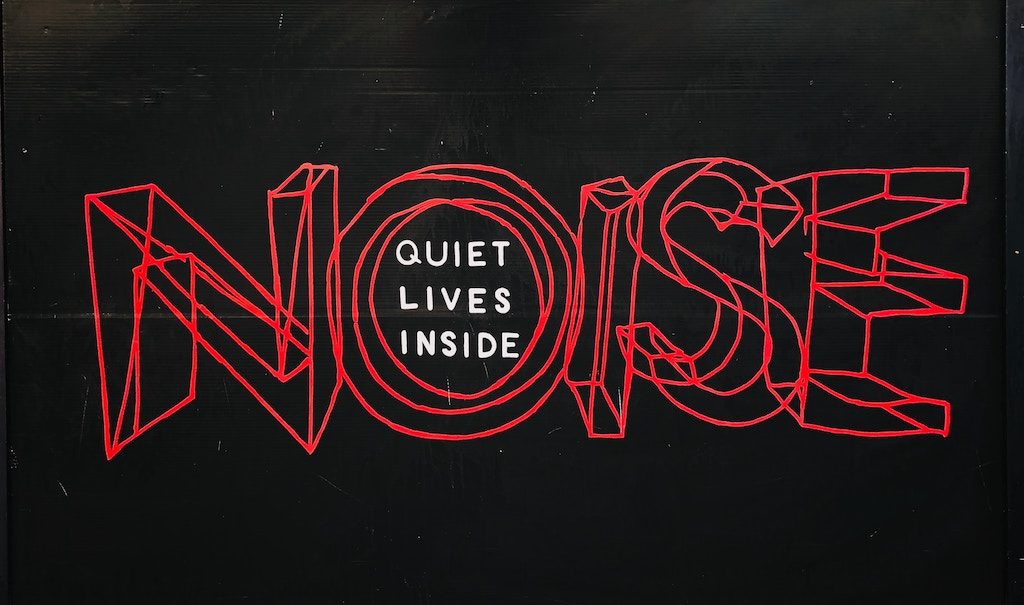

The human brain processes between six and eight thousand thoughts in a day, and it seemed to me that all my thoughts that evening were worrisome. My rumination about a probable discomfort brought me a real discomfort. My empty bladder felt as if on the verge of exploding and emptying with a flood. But, in fact, the only flood was that of thoughts deluging my mind. The noise was as heavy as a container filled with the entirety of an ocean; as dense as a pie made of rocks.

I thought I should introduce some movement to juxtapose the noise, so I opened my suitcase to realize that, like always, I had over-packed. I slid the bag under my bed and decided to climb the tree ladder. What a moment before was my ceiling now was the floor supporting me. The wall was a window that opened to more trees, all green and towering toward the clear blue sky.

For the past nine months, I have been enrolled in yoga teacher training. In April, I completed my first 200-hour yoga teacher training that enabled me to teach hatha and vinyasa yoga, and I continued with the yin yoga training. In the course of my training, I’ve spent hours listening to the silence around me, connecting to my breath, resting in stillness. However, I haven’t walked the path alone. I had my teachers to support me, I had my community. On the evening of May 2, I was alone.

I was alone in a tiny cottage surrounded by tall evergreen trees and narrow trails that branched like sunrays, leading deeper into the forest. I was alone in the woods, and my mind was filled with noise.

But this noise inside me was not all mine. A significant part of the noise in my mind is of this world I’m always trying to understand. The world that weights down on me, pressing onto my chest with the mass of a mountain.

I thought I could release the weight through writing. I thought I would just write and write and write until my fingertips bled. But I didn’t put a word on paper. Not a word.

Instead, I started to count my inhales, then my exhales. I inhaled on the count of four, and I exhaled on the count of five to liberate my mind from the bothersome three.

The mind loves chores. Counting breaths makes for an excellent method. After the third round of breathing, a new thought arose. An inquiry. What is the sound of silence?

To some people, the word silence suggests the absence of the sound. But silence is not soundless. Is silence the absence of noise?

There are words that, although clearly defined in dictionaries, don’t hold meanings.

Absence is one of them.

In the opening of When Women Were Birds, Terry Tempest Williams described the days following her mother’s death. “Her absence became her presence”, she wrote. And I thought intensely about this sentence.

The absence of noise inside my cottage became the presence of many different sounds.

The sound of a creek nearby; the water running and hitting the rocks.

The sound of the wind tousling the leaves on the high branches.

The sound of the wind whispering to the birds.

The sound of the birds in the evening.

The shriek of the angry chipmunks reprimanding me for occupying their space.

The sound of my neighbor stepping over the pine needles.

The sound of my own breathing on the counts of four.

And then, finally, the sound I was hoping to hear: the one of my heart. Thump. Thump. Thump. Then on, louder and faster. Thump thump thump thump thump.

Silence appears in the absence of noise, harmonious, and regenerative.

Silence is the mother of sounds. Silence is the beginning.

I often think of beginnings. All writers do. Our days begin with a blank page.

A wordless page. Our days begin with silences that give birth to sounds.

Everything began with the sound. The Big Bang created the Universe. According to Vedas, the oldest Hindu texts, it was the sound of OM that created the Universe. In Christianity, we find John’s words (John I: I), “In the beginning, there was the word.” In the teachings of Buddha, we learn the Brahma sound, the transcendental sound that has the power to create worlds.

I inhaled the silence of my cottage, and I let go of the sound of AUM. The longest that I’ve ever released.

I don’t know how long I sat in my loft. I lost track of time. The sound of my belly growling informed me it was the dinner hour, the sound of my knee popping told me it was time to stretch my legs.

I ventured out to the town of Langley, Washington and found a bistro where I made a new friend.

My new friend told me about the silence that had crept into her house when both of her sons had left for college. It was a distressing silence, demanding attention and response. To answer the demand, my new friend and her husband moved to a new house, to a new town, to a different state. There too, she now has access to silence, but the new silence is not an absence of her sons’ voices. The new silence is her silence and it’s rich with sounds of the new place.

My friend’s new silence is the beginning.

When I returned to my cottage, I remembered that I had a passage from Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse written somewhere in my journal.

For now, she need not think of anybody. She could be herself, by herself. And that was what now she often felt the need of – to think; well not even to think. To be silent; to be alone. All the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being oneself, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others… and this self having shed its attachments was free for the strangest adventures.

I read this passage a few times out loud, letting the Woolf’s words fill up my space. Then I filled my lungs with breath, held for four seconds, and let it all out, audibly. In the silence of my tiny cottage surrounded by tall evergreen trees and narrow trails that branched like sunrays, leading deeper into the forest, I emptied out the noise I had brought in with me. Shapeless, the noise quickly evaporated, and all that was left in my mind was the warming feeling of gratitude. I was grateful for the gift of scholarship that Hedgebrook had presented me with so that I could be in this room of sacred silence, and for the support of my husband who embraces me the way I am and provides the space for me when I need to (re)connect with the silence, not thinking, not doing, just listening to my heart. I was also grateful for the lives and struggles of the women who paved this path before me. The women writers, the women artists, the women in politics, the women in science, the priestesses, the attorneys, the healers, the witches, the rebels, all the women warriors of light who refused to be silenced.

I cannot write about silence if I don’t write about the importance of the voice or one’s right to have and express voice.

I am raising two daughters, and I want them to have strong voices. Strong is not a synonym for loud, I tell them when their voices, mostly overlapping, are ripping the skin of my inner ear. My mom is visiting, and she also has a strong need to voice everything out. When I’m driving us places, the three are talking at the same time. Louder and louder, their voices grow, overpowering one another. The four-year-old and the sixty-six-year-old are simultaneously and similarly asking for my attention.

I choose to remain silent and to breathe.

In When Women Were Birds, Terry Tempest Williams explores the voice in fifty-four chapters. She writes, “When silence is a choice, it is an unnerving presence. When silence is imposed, it is censorship.”

I am not dealing well with too much noise. I choose my music, my spaces, my company. Yet, my two daughters are louder than a dozen. I tell them that for a voice to be heard, an act of listening is necessary. I am good at listening. But I am not good at discerning through the noise.

But no matter how much their noise disquiets me, I do not want to silence them, so I let them scream it all out. Emotions – out. Fear – out. Sorrow – out.

In ancient Roman mythology, Diva Agerona was a goddess of silence. She was usually shown with her finger over her mouth, requesting silence.

Unfortunately, little we know today about this goddess. There are several mentions that she was protecting the secrecy of the name of Rome or that she might have been the goddess of secrets. When I think of her, I imagine she was a goddess of the inner voice.

“Finding one’s voice is a process of finding one’s passion,” Terry Tempest Williams This agrees with what I have been telling my writing students to remind them that we must find the burning place within ourselves and write from that heat. The story we are chosen to write is the one that sets us on fire.

I wrote a novel to explore the importance of the inner voice. It took me seven years and a grad school to complete it, and I still don’t love it enough to share it with the world. But, I had one chapter of a new project that has been burning that intensely inside me that I dared read it at the Vortext’s open mic event. I read the raw beginning of my new story in front of the room full of women writers. Amazing writers. Natalie Baszile, Dylan Landis, Ruth Ozeki, Shobha Rao, Elmaz Abinader, Rahna Reiko Rizzuto, Karen Joy Fowler, and Amy Wheeler were there in the first row, listening to me, and I knew that this was just the first time I would read these pages. There will be many more readings and even larger audiences.

Later that evening, all the women told me that they loved my voice. It was my voice that came through. Not the story, not the character, not the language.

When the second night came, I rushed back to my fairy cottage in the woods to find my silence again. There was just la Luna shining through the green coat of the forest and me. The silence I encountered was a felt experience. It penetrated my skin and pierced through my bones. It intertwined itself in-between my ribs and filled my lungs.

The next morning, at breakfast, I sat next to a woman whom I told about my silence. She told me that, twenty years before, when she had been awarded a Hedgebrook residency, she experienced the solitude for the first time. In the solitude that she described as absolute and profound, she had found a nourishing stillness that has never left her. “If you can truly connect to the silence that resides within you,” Anne said, “you will go on, forever carrying your inner peace.”

It’s been two months since I came back from Whidbey and I’ve been telling everyone about the sound of the silence inside my tiny cottage in the forest. Every day, I think of Anna and her words. Every day, I silently thank her.

Silence inhabits my heart.

Silence is not the absence of sounds.

Silence is the home to my voice.