First published in the 1930s and 1940s, C. L. Moore’s collection of short stories embodies the otherworldly appeal of science fiction during that time, echoing America’s growing fascination with space exploration and its rapidly expanding multicultural awareness. But Moore’s stories were a level above the typical sci-fi pulps of the day. She confronted the fallacies of ethnocentrism, colonialism, and gender bias head on, taking a leap into the future of science fiction like the badass female writer she was.

Take the story “Shambleau,” for instance. Here, we meet interplanetary adventurer Northwest Smith, who’s visiting from Earth and decides to rescue a beautiful alien girl from death at the hands of an angry mob. In just a few sentences, we get a sense of Smith’s self-entitlement, and of how Shambleau’s differences defy his narrow definition of humanity:

“He… stared at first with curiosity and then in the entirely frank openness with which men regard that which is not wholly human. For she was not…. He knew it from the moment he looked into her eyes… they were frankly green as young grass, with slit-like, feline pupils that pulsed unceasingly, and there was a look of dark animal wisdom in their depths.”

Even the liquor in Shambleau’s hometown is a challenge for larger-than-life Northwest Smith, who gets blazing drunk and then struts down the streets of a foreign planet with complete disregard for his own safety:

“…much later Smith strolled homeward under the moving moons of Mars, and if the street wavered a little under his feet now and then— why, that is only understandable. Not even Smith could drink red segir at every bar from the Martian Lamb to the New Chicago and remain entirely steady on his feet.”

In a haze of self-confidence not entirely due to the segir, Smith lets Shambleau shelter in his hotel room even though he knows the mob believed she was dangerous. Then, Shambleau unwinds her turban to reveal a head full of snakes.

Does Smith do the smart thing and run? Of course not. To him, Shambleau is an exotic woman longing for a man’s touch. Spoiler alert: Smith nearly gets the end he deserves, but his friend arrives just in time to rescue him. So much for interfering in the local culture and taking advantage of alien women! After that, Smith is never quite himself again.

“Vintage Season” is another great example of Moore’s approach to cultural and racial bias. On modern-day Earth, Oliver rents rooms in his house to three tourists. He’s fascinated by their clothing, manner of speaking, and intelligence, and he attributes their beauty and self-confidence to their ethnicity. But he doesn’t know that instead of being from another country, his visitors are from another time: the future.

Even though Oliver is engaged, he develops a crush on Kleph, one of the visiting strangers. He can’t help but compare Kleph’s perfectly fitting clothes, blue eyes, and tanned skin with his fiancée’s brown eyes and not-so-beautiful chin. To Oliver, Kleph represents another race and another world unlike his own, a world that he wants to be part of.

So when Oliver and Kleph share a beautiful omnisensual experience of music from Kleph’s time, Oliver imagines that he is becoming more like her:

“[He] was interested to see in him an extension and a variation of that extreme smooth confidence which marked all three of the [visitors]. Clearly a racial trait, he thought.”

However, it’s not long before Oliver is rudely awakened. He discovers that Kleph and her companions are time travelers from the future, and they leave just before a meteor destroys most of Oliver’s city. Not understanding why the time travelers refused to interfere with the past, Oliver is furious that they knew of the meteor crash but didn’t warn anyone.

He falls deathly ill, but leaves a note for other time travelers to find, asking them to go back in time and warn the city to evacuate. But ultimately, his attempt is futile, just like he failed to enlarge his own ego by tacking Kleph’s culture onto his own. The result is quite the opposite of what Oliver really wanted. Instead of connection and love, he is left alone and forgotten.

Besides writing a damn good story, Moore asks us to question our motives. When our fascination with those we perceive as “the other” is driven by a desire to conquer that otherness and make it our own, the result is separation and despair: segregation, genocide, racism, and all the related problems we continue to see even in the twenty-first century. If, on the other hand, we communicate with others out of respect and without appropriation, there’s hope. Moore reminds us to take off our ethnocentric-colored glasses and appreciate the variety of people on our planet (and beyond) without judgment, a reminder that we need now more than ever.

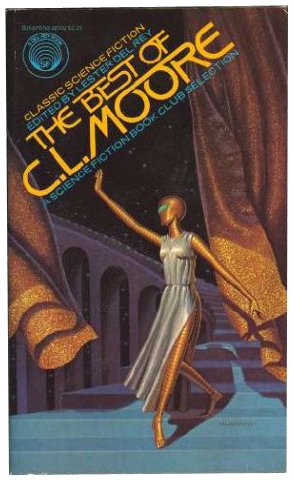

Look for The Best of C.L. Moore at your local library or used bookstore.