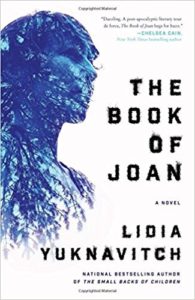

Thematically a dystopian novel, Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan is the author’s genuine way to fight against the apocalypse, against the fear of geological catastrophe and of Earth’s dying and turning into ashes and dirt.

Thematically a dystopian novel, Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan is the author’s genuine way to fight against the apocalypse, against the fear of geological catastrophe and of Earth’s dying and turning into ashes and dirt.

The story unfolds in our near future after Wars have transformed the planet into a radioactive battleground. The cities and countries have lost shapes and names. Humans are almost extinct. A group of people led by a sadistic military leader and former reality show host Jean de Men ascended to CIEL, a hovering, parasitical platform that sucks on the sad remains of Earth’s energy.

After years of living above ground, these humans have become sexless, hairless, and white as paper.

Deprived of bodily pleasures, and the ability to procreate, the post-apocalyptic mammals practice skin-grafting as their only form of art. Their colorless skin has become a canvas on which skin-graft authors exhibit their virtuosity.

In The Book of Joan, two women’s stories are threading through one another. The novel opens with the voice of Christine, a well-known skin-graft artist, who, in her last year of life (on CIEL, humans are being executed at the age of fifty) brands a story of Joan of Dirt on her body. Yuknavitch based Christine’s character on the historical figure of Christine de Pizan, an Italian-French medieval author who served as a court writer to several dukes but became an important feminist figure because of her work The Book of the City of Ladies and The Treasure of the City of Ladies. De Pizan created an ideal city where women were appreciated, where their voice was heard. De Pizan’s last piece was a poem – a eulogy for Joan of Arc. The character of Joan of Dirt is, as you may guess, a lyrical version of Joan of Arc, the woman who has been the author’s obsession since childhood.

On CIEL, the residents can’t hide anything – their heart rate, biological status, even their thoughts and dreams are recorded. Anything that resembles an act of sex is considered a crime. Trying to cheat death and live beyond the age of fifty is also a crime. All sex is restricted to textual, and the only form of text are body grafts.

Cleverly, Yuknavitch deprives her characters their pleasures and takes away all sensory detail from their bodies to prove, once again, that it is the body that holds a narrative. “It’s our idiotic minds that overwrite everything. But the body has a point of view; it keeps its secrets.”

In The Book of Joan, burning of the body is an art. In Jean de Men’s trivial world burning is also a show. After Jean de Men had imprisoned Joan (a child warrior who, instructed by the song of God she had heard in her head, raised an army of men against him), he threw her into the fire, then broadcasted her burning. But somehow, Joan escaped. The truth that Joan of Dirt is still alive is known only to her chronicler Christine and her soon-to-be-executed friend Trinculo. Since both Christine and Trinculo are living their last days on CIEL and have nothing to lose but their doomed, sexless bodies, they are determined to find Joan and fight the apocalypse.

Down on the dying Earth roams Joan and her lesbian lover. Joan has the power to manipulate the elements. And just like her heroine, Yuknavitch manipulates the elements – those of her narrative. She embodies her characters, blurs the line between history and fiction, and even changes point of view as the novel progresses. We first hear Christine’s voice in the first person and Joan’s in the third, and later the author switches letting Joan talk in the first person and Christine in the third. The two women are drawn closer together by Christine’s writing, by the words on the body, by the power of the body. “The body is a real place. A territory as vast as Earth.”

Lidia Yuknavitch abandoned the trope of the main character a while ago. Her novel The Small Backs of Children (a hybrid made of prose, poetry, scripts, letters, fragments, and juxtapositions) had a cast of characters who were laced together by a story. “People’s realities are threading through each other’s experiences,” explained Yuknavitch. That is why she has little interest in the plot as well. Especially the one controlled by a writer. The actual life’s plot is a chain of events. Every event is generated by its precedent and a cause for the story that follows. The job of a writer is to imagine a big bang.

Using her cast of characters in The Small Backs of Children (the Girl, the Writer, the Playwright, the Poet, the Photographer, the Filmmaker, the Painter), Yuknavitch explored the themes similar to those in her memoir The Chronology of Water: the making of art, violence, and body. The Small Backs of Children was a book of the body and bodily fluids. Yuknavitch wrote from the body with the intention to reach other bodies. In The Book of Joan, Yuknavitch uses the body to tell the story, but she reaches far beyond the corporeal, into the essence of everything, into the matter. “Everything is matter. Everything is moved by and trough energy. Bodies are miniature renditions of the entire universe.”

In The Small Backs of Children, Yuknavitch wrote on the borderline between truth and fiction. The Writer character is a version of herself – we can see this clearly from the first Writer’s appearance in the novel. The Writer echoes Yuknavitch’s experience previously shared in The Chronology of Water. “Any writer’s knots are embedded in whatever story they tell,” Yuknavitch said through the voice of the Writer. “I have invented hundreds of selves. Men and women. I have peopled the entire corpus of my experience with fictions. Who is to say they are not I? I them?”

In The Book of Joan, Lidia Yuknavitch echoes history because she believes that history isn’t and shouldn’t be locked in the past. “Let’s say time isn’t linear,” she said at her reading in Seattle. “There are some books and movies today that play with the idea that the past can re-emerge in our present.” And what happens in the end of The Book of Joan proves her statement. The stories of Christine and Joan merge in a way that we cannot tell for sure whether it was Christine who had imagined the story of Joan and then made Joan live it or she was just a witness, a chronicler of the heroine’s tragedy and victory.

And does the knowing make any difference? The story is told and retold. The characters live and die and turn into matter and then they are born again.