Uschuk, Pamela.

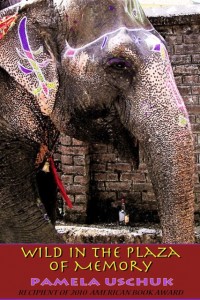

Wild in the Plaza of Memory.

Wings Press: San Antonio, TX. 2012.

$16.

Reading Pamela Uschuk’s Wild in the Plaza of Memory, I imagine a particular coterie of writers and artists, all vying for attention, all yearning to be heard in the poet’s brain. Around the gray matter table sit Mary Oliver, James Dickey, John J. Audubon, John McPhee, Jon Krakauer, and Martin Heidegger. As the poet writes, she overhears the group’s voices, each suggesting subject, theme, image, or tone. Each knows he can be asked to leave if too assertive or too demure, so he hints, cajoles, seduces, and entertains rather than brays.

Like Mary Oliver’s transcendental-minded personas, Uschuk shares intimate autobiographical details describing her many Walden Ponds. She turns ugly into beautiful and magical by foregrounding context: “Say the fist-sized toad disguised himself as mud, / left only his outline beside the butterfly bush / when he vanished into dusk” (“Say What”). Seen through Uschuk’s lens, the awkward ugliness of the wrinkled brown toad, when set against a “butterfly bush,” disappears like a furry magician’s rabbit. Like Oliver’s verse, God is in the details: “God is the tongue of the female timber wolf slathering / my face, rough as a snow shovel” (“Whole Notes”). The striking paradox of getting tongued by a wolf, her deadly fangs close as breath, creates terrific tension, and defining God as the collusion of intimate danger invites us to consider a whole new understanding of how close, not distant, God lives.

James Dickey does not allow Oliver to control the collection’s mood; his voice pushes Uschuk to settings wilder, sexier, and more conflicted. In “Green Rain, a Birthday Poem,” the poet lists her loves: “sheer rock faces where goats cling / in thick white robes judging no one, not / the root-beer colored eyes of grizzlies / nor menstrual cramps of thunder / cracking the sunny intent of sky.” There’s a gutsy quality here that grabs and holds us. “Cloud Gathering,” dedicated to husband William Pitt Root (and fellow editor of Cutthroat where, full disclosure, I recently had a piece of flash fiction published), shows us “Ute buffalo / bulldoze spring grass they chew, recalling / wolf and coyote opening the bag / of creation,” then juxtaposes the divine creation with the human: “Love, I think of how I reserve my hipbone, the inner / flesh of my lower lip for you on a Sunday like this / when wind gushes in from snow-dazed peaks.”

The poems’ natural imagery ranges well beyond the large fauna of wolf and buffalo. Audubon’s birds fly in and out of several poems, many taking wing with ornithological first lines: “Not the California quail clucking for millet”; “The full moon eats the screams of magpies”; “It’s the solace of lazuli buntings”; “The goldfinch carries sun on its back.” Perhaps birds act like a talisman Uschuk rubs for good luck, Homer appealing to his muse. However, birds also nest in the thick of things, here sharpening the focus of a storm’s power: “After last night’s storm that slashed / nuthatches from trees…” (“Learning Subtraction”); and “thrushes signing from a wet awning of oak leaves, the saturated flutes of canyon wrens and turquoise violins of lazuli buntings” (“Green Rain, a Birthday Poem”).

Set against this motif—or, perhaps, complementing it—literal rock-hard data is composed with John McPhee’s metaphorical flourish: “huge rocks that flex like black vultures”; “boulders the size of inflated elephants”; “This rock is as big as a garage and talks our ears off” (“On Pigeon Mountain: City of Rocks”). The humans who inhabit this rocky tableau seem less sensate than the terrain, “the lichen-cloaked hermit rocks / …recite sutras among Appalachian blueets, / polygala, the sticky yellow tongues of honeysuckle.”

The book’s middle section, “A Short History of Talking,” in part chronicles Uschuk’s Himalayan odyssey, a kind of poetic Outside Jon Krakauer travelogue. Populated with equal parts bird song, mountain peaks, tortured women “raped by cattle prods” (“Focus of the Mind’s Labyrinth”), and the Dalai Lama, the poems comprising this interior chapbook take big risks that pay off. “Who Today Needs Poetry” lists those who don’t need it (“not the healing odor of white oleanders fencing the yard, not the pinched skin of saguaro / cactus nor the glitter of sunrise caught in their gold thorns”), the accumulation of sensory images, autobiographical and historical, bombarding the reader’s sensibility up to the last lines, “No, not any of these. / Not these,” meaning everyone and everything else, recalling William Carlos Williams’ dictum that people die for lack of poetry daily.

Finally, Martin Heidegger’s long essay, “The Origin of the Work of Art” (in his Poetry, Language, and Thought), posits that, of all the arts, poetry best “unconceals” truth “as the poet composes a poem.” Language reveals what lies behind the veil of reality, removes “ourselves from our commonplace routine…so as to bring our own nature itself to take a stand in the truth of what is.” While poetry grounds us, it also alerts us to “something worthy of questioning, something that still has to be thought through.” To accomplish this, art displays “a thingly character, albeit in a wholly distinct way.” To examine, to expose, to “open” “the thingness of things” reveals the true nature of being.

Uschuk’s work accomplishes this. Her verse directs our attention to the extraordinary in the ordinary, the beauty in the plain, and the complexity in the banal, unconcealing the being lying hidden in plain sight. This unified vision of disparate parts impresses us, in Heidegger translator Albert Hofstadter’s words, with the “intimacy of world and things,” and “the complete opening of the human spirit.”

This revelatory nature (often literally) of Uschuk’s poetry is first offered in the book’s opening epigram by James Wright, the meaning of which the rest of the book unconceals:

It is here. At a touch of my hand,

The air fills with delicate creatures.

From the other world.