The dumbest part about funerals is the minister, who always ends up saying something like I didn’t know the deceased but — and then a long string of very nice generalizations. Ryan had a good soul. He was a lover of nature. People tended to like Ryan. But the thing is, funeral remarks are above criticism in a way that the standard Sunday service stuff isn’t. If it’s just another Sunday in June, I’m allowed to say that the sermon didn’t make any fucking sense, and how like maybe the Romans 6 reading pretty much contradicts all the good stuff in last week’s Luke 10, and Isabelle will listen and nod as I make my points and tell me it’s good that I’m engaging actively in the lesson, that I’m very smart, and then I get a little kiss. Her parents are deeply religious, and the deal was that if we were going to get married right out of college, Isabelle had to take me to church literally every Sunday. But yeah, definitely the open dialogue stuff does not fly for funerals. Even with my eyes closed in pretend prayer, I can’t help but hear Isabelle’s tiny, rapid breaths. Her head hangs, auburn hair curtaining her face, and she’s crying. I cannot pretend she’s not crying.

The minister wears a colored scarf and has a sort of canine droop around his cheeks and jaw. He welcomes the Jefferson College Sigma Theta class of 2009 up to the stage for what I personally think is the worst idea we’ve come up with as a class since the whole cream and soda party of 2007. All nineteen of us rise from our fold-out chairs — Isabelle giving my hand a reassuring squeeze — and file out into the front of the congregation. It’s that first really nice day of the year, when the new warmth on the breeze always has, for me, this oddly sexual feel — some vague and unfortunate sensory association that must go all the way back to truth or dare in the woods beyond my middle school playground. Hillside Memorial Parks is all rolling hills and trees, with a view of Montgomery Pond in the distance — the smell of pine needles is inescapable.

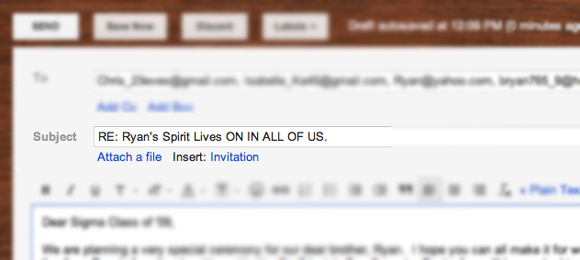

In theory, each Sigma 09’ has memorized a line from the St. Crispin Day speech in Henry V, supposedly Ryan’s favorite play, although this claim remains unsubstantiated and highly suspect as far as I’m concerned. Stephen Thayer, our class’s Grand Procurator, was “one hundred fuckin’ percent” that he’d heard Ryan mention it “at some point Freshman year.” I’m one hundred fucking percent that Stephen is somehow confusing Shakespeare with a popular HBO series on WWII, but whatever, I wasn’t going to throw that into the highly emotive email chain subject line RE: Ryan’s Spirit Lives ON IN ALL OF US.

Yet another unintended consequence of living in Charlotte is that I have no realistic excuse for missing this funeral except maybe to say that I’m sick, but of course then everyone will say what difference does that make, come anyway this is important, and I can just see the email chain subject line RE: Chris is For Some Reason Being a Fagnuts Asshole, and of course I can’t claim to be really sick like flat-on-my-back sick because then I’ll have to make Isabelle complicit in the whole thing. Which is not an option. And so here I am in line with my fraternity brothers in front of everyone, and we go one by one, from “If we are marked to die” all the way to “And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks that fought with us upon St Crispin’s day.” And it might have at the very least been a nice show of solidarity if nothing else, except a bunch of people fuck up their lines and Craig Marshall somehow manages to forget his and has to fumble into his breast pocket for a crumpled internet print off. Funerals are a joke. All the little ceremonial things people feel it’s necessary and important to do. When I die I want my next of kin to orchestrate a Bacchic frenzy in my backyard where everyone gets drunk and has sex and forgets about me entirely. Stephen recites the last line and we all just stand there staring out into the congregation, who all look appropriately somber and moved, Isabelle trying to give me a little smile through tears, until the minister tells us we can return to our seats.

The next part of the funeral is the only part that really matters, and I suppose I’d allow a brief interlude in my bacchic frenzy for it — the personal anecdotes, where friends and family go up and share something that’s supposed to exemplify the deceased’s unique worldview or sunny outlook or something along those lines. Stephen Thayer is invited back up to the podium.

It’s funny how these remembrances work. The way you include some details and omit others in order to present a coherent personality. Stephen’s story place on a spring break trip in our sophomore year, the oft-repeated tale of Ryan Drury saving the local Florida Keys girl from drowning. Stephen includes the part about Ryan striping off his shirt, peeling the polo inside out as his spine arcs back. The part about this girl’s limbs moving rigid in the water, plastic action figure limbs, and Stephen really isn’t exaggerating much when he says she would’ve drowned if not for Ryan’s intervention, his diving in and wrapping a thick rugby forwards’ arm around her ribcage as their legs thrash and tangle, Ryan now struggling to support the new weight. Stephen stumbles through all of this and even remembers to mention the strange almost-silence that reigned the entire time, the notable lack of any verbal exchange between rescuer and rescuee, not even a simple “don’t worry” or “I gotcha.” The slap of Ryan’s free hand hitting the water, the thresh of his abbreviated strokes, the jagged, mucus breaths of the girl. An almost-silence in which you might infer a psychic and kind of beautiful understanding between the two of them. For Stephen it’s that “he didn’t need to say a word,” which might have been a nice place to stop, but Stephen also decides to mention the fact that after she’s choked up roughly a quart of seawater and what looks to be a little oatmeal onto the deck of their rented motorboat, Ryan extends an invitation to their party. And if you want to sum Ryan up as a “generous spirit”, as Stephen does, then you really must end the remembrance here. You definitely can’t keep going. You can’t mention the part in the hot tub when she turns away and puts a hand on his massive chest as he tries to kiss her, or the way she smiles and looks around to find no helpful or reassuring faces, no “Hey, woah, let’s cool it.” There’s no one even remotely familiar. You also can’t describe Stephen, in his wayfarers, oxford shirt, and boxer briefs look, the one he thinks is so fucking cool — Stephen that little fucking chemist going to work on his special punch that you really have to taste to understand, the delicate proportion of white-hot grain alcohol to low calorie, high sodium sports drinks that somehow cancels out, reduces what should have been a warning burn to more of a simmer in the aftertaste. And the funny joke here is that I start to run out of details. The part when the punch gets passed around. The part where I don’t really do anything, when I become complicit. Everyone else can project their own memories. But I do clearly remember that my room, with ocean view and floppy ceiling fan, was the one right next door to Ryan’s, and I remember that at some point in the early morning, before the sunrise even, she began to cry, just little wet sobs at first, gradually rising into those bigger airless gasps, and then the sound of mattress springs shifting as Ryan’s voice comes muffled through the wall. And for some reason it’s not gravelly and merciless and loud, as I would’ve liked, but soft and actually sort of paternal, this long, formless speech, and as much as I strain in the dark, cupping my hand to my ear, I can’t make out what it is he’s saying — and what could he possibly be saying? — and all I’m left with is the muffled sound, this calm, oaky timbre that I will never hear again.

The congregation can’t clap but some people nod their heads in approval as Stephen gathers up his notes and steps down from the podium, and the general sense I get is that everyone is pleased and sad.

I think about what my own remembrance would be, not that I was asked to do one, but still. I know what details I’d choose to include. That it’s one of the first warm days of spring, and we’ve all agreed to skip class and drive to the lake. I mention that Ryan always has to be the first one in the water, and I describe the way he takes off screaming across the dock, hands in the air, feet coming down in a heavy patter on old wooden planks, almost a cartoon of himself, leaping off the end and not getting enough height and going way too fast to even think about completing the forward flip, and we all watch as his he-man, barrel of a body sort of whiplashes into the water, head first. A silent, panicked moment, and then Ryan’s arms emerge from the water, hands closed into fists — a superhero punching through a wall — and he’s already howling in joy as his head breaks the surface. This is an example of Ryan’s courageous, fun loving spirit, I say.

The details I omit. The part when he hauls himself onto the dock and everyone high fives and punches each other in the stomach, and I look over to where the girls are setting up their beach towels and see Isabelle. I think she’s in the act of putting sunblock on her shins, ankles and, toes, which really do burn if she’s not careful, but when I really look I see she’s sort of on pause, a gob of sunblock cupped her left hand, absently picking at a scab on her ankle with her right, and she’s looking over at the dock, at him. He’s flexing his muscles to show he’s OK, that even after hitting the surface of the water with his neck at that sickening angle, he’s still completely unhurt, flexing while everyone laughs. And I can’t be sure, and it’s not really fair, but in that moment I think the look on her face is the look of absolute attraction, the look of female to alpha male as dictated by some evolutionary hardwiring, the desire for safety and security and the assurance of future resources, her eyes wide and the little smile just beginning to curl on the edge of her lips. A smile I’m sure she’d deny even in that moment.

The minister returns to the podium to admit that while he didn’t know Ryan personally, he’s been quite overwhelmed by the outpouring of love and support from everyone who did. And here I’m surprised, because the minister doesn’t go on to make a generalization about Ryan’s character, but rather a generalization about us, the congregation. He says that he knows Ryan will live on, in our hearts and in our dreams, for the rest of our lives. And as the portable keyboard plays us out and everyone begins to rise, I have this thought, this idea of a nightmare I could potentially have, and I hope that I’ve precluded the possibility just by thinking about it. I’m lying on a strange bed in the dark, and in the room next to mine someone is crying. And it soon becomes clear through some sort of dream logic that that person is Isabelle. And I know that any moment I’ll hear the bedsprings shift, hear that soft, muffled voice, the father’s voice, soothing her back to sleep.