Drawing, painting, video, and performance are all mediums our December Artist utilizes in her involved, relevant creations. Native Iowan turned Kansan, Amber Hansen proudly represents the Midwest. Beginning her artistic endeavors early on, she was determined to learn despite the lack of artistic outlets/resources in her small, rural Iowa community. Eager to continue learning, Amber received a BFA in painting and printmaking from The University of South Dakota and immediately followed up with an MFA in painting and drawing from The University of Kansas.

Growing up on a self-sufficient farm, Amber’s unique experience has contributed to the organic and relatable feel of her artwork. She’s both interested in everyday experience and relevant social issues. Both finite details and the big picture. Her drawings are playful, inviting the viewer to consider, compare, and understand. She takes risks, producing work that surprises and pushes boundaries.

In our interview, we concentrate on Amber’s development as an artist, her artistic process, her involvement in mural-making, her series Learning is Remembering, and her most recent project The Story of Chickens. From murals, to revisited childhood drawings, to chickens (or the lack-there-of) in mobilized coops…there is something for everyone in this Pif exclusive.

Can community-inclusive art produce quality work and promote community cohesion? Can a coop full of fowl be considered art? Can combining old and new drawings provide enlightenment? Let’s find out!

Emily Frankoski: How long have you been creating artwork? What were you like as a child/how did you spend your time?

Amber Hansen: As a child I spent much of my time playing and working on my family’s small acreage. My sisters and I were constantly making things: popsicle stick villages, clothes, quilts, forts, candles, paintings. I was immersed in an environment that required a great deal of ingenuity and creativity. My painting skills were often utilized to create signs and murals. We worked outside until the sun went down. When we came in for the night, my family would watch TV while I painted in the dining room. Night was the best time to work uninterrupted.

Amber Hansen: As a child I spent much of my time playing and working on my family’s small acreage. My sisters and I were constantly making things: popsicle stick villages, clothes, quilts, forts, candles, paintings. I was immersed in an environment that required a great deal of ingenuity and creativity. My painting skills were often utilized to create signs and murals. We worked outside until the sun went down. When we came in for the night, my family would watch TV while I painted in the dining room. Night was the best time to work uninterrupted.

Living on a farm, I was surrounded by animals and enjoyed being near them and caring for them. At an early age I became aware of the great responsibility demanded for their care. I have learned a great deal from interacting with animals and this continues to impact my relationships with people.

From a young age I was motivated to be an artist and to raise horses. The community I grew up in lacked the necessary social networks, so these became more or less solitary endeavors.

EF: Describe your artistic progression through life or journey to becoming an artist.

AH: When I was four years old I was diagnosed with French Polio and spent two weeks recovering in the hospital. During that time, my Uncle Terry visited and drew two pictures for me. Referencing some of my stickers, he made a drawing of a horse and Superwoman. After seeing how well he could draw, I resolved to do as well.

I had a couple of relatives who would sit down and teach me things at family gatherings, but most of my skills were self-taught from books and videos. My community was supportive, but as I said before, there were few resources for me to utilize. I was eager to attend college and continue my development as an artist.

After graduating from high school, I attended the University of South Dakota where I received a BFA in painting and printmaking. I enjoyed my time at USD and think fondly of its creative community and the impact on my work. While just a small program in an isolated town of South Dakota, it offered an array of vibrant and dedicated professors and students. I also met my partner, Nicholas, here. We continue to collaborate on many projects.

Immediately after graduation I applied to graduate school and was accepted by the University of Kansas where I received an MFA in Painting and Drawing. Both Nicholas and I were accepted to the graduate program. I knew that I wanted to learn more and wanted to teach at a university, so graduate school seemed appropriate. KU offered many possibilities, including the opportunity to teach.

It took a long time to become convinced that art was a worthwhile, longterm pursuit. Today, I realize that art is essential to me. I am completely in love with what I do in every way.

EF: What drew you to art as a career?

AH: To begin with, I was enamored with the idea of drawing. But the more I learn about art, the more I realize how important it is to individuals and to communities.

EF: How has your career progressed since graduation?

AH: Since graduating from KU I have spent two years as artist-in-residence at the University of Kansas. I taught life drawing and expanded my research into multi-media projects. I’ve also had the opportunity to do extended collaborations, most recently with a super artist named Jamie Lacore, creating music, videos and performing. The Story of Chickens, a community-inclusive art project, was created during this time. I was lead assistant to artist David Loewenstein on Mid America Arts Alliance’s community-based mural projects in both Tonkawa, OK and Joplin, MO. In Joplin, I worked both as a painter and a documentarian for a film titled Called to Walls. I’ve exhibited in group and solo exhibitions nationally and my drawings are currently on display in the Kansas City Collection II.

EF: Describe your artist residency at KU a bit more. Did this period of time help or hinder your art creation?

AH: I am grateful for both the time and space it offered to develop new work, and for the opportunity to teach. I learned a great deal from teaching others how to draw and solve visual problems. Each class was as helpful to me as it was to them.

EF: Has growing up on a farm impacted your artwork? Does it contribute beneficially to the content of your artwork? If so, how?

AH: Growing up on a farm continues to impact my work. I’ve spent a lot of time with domestic animals and those memories continue to influence. On the farm I developed a strong spirit of ingenuity. We built what we needed or wanted, using salvaged materials from unwanted buildings. We were all artists. Problem solving and creating were continuous…sometimes for practical reasons, but other times just to make something beautiful.

EF: What other variables have inspired the direction of your artwork?

AH: My work is informed by everyday experience and my own personal research. I am inspired by artwork and artists in my life. I’m inspired by old ideas that have almost been forgotten. I’m also sensitive to the affects of our cultural and visual environments on quality of life. I find inspiration in travel, but continue to be drawn to the culture and environment of Middle America, an area I have spent all my life getting to know. I like to transform everyday objects and movements into something unexpected and new.

EF: How do you get your work “out there” for public viewing?

AH: That is a continuous effort. I apply to various venues to display my work. I also apply for grants to fund current and future projects.

EF: What mediums have you used in your artwork? Do you have a specialty? Describe your development through medium.

AH: I use many mediums, including drawing, painting, video, and performance, but my foundation is drawing. Drawing is where it all began for me and remains my gateway. For example, in grad school I was making this drawing of legs running across a field. I liked the visual components of the piece but the drawing itself was not that interesting so I decided to create the situation in real life. I went around town asking people to participate, and when I was able to summon about 15 people, we met to make a video. The experience of making the video was amazing. It brought the sketch of my idea into another dimension. From that moment, I began to work between drawing and video/performance. I have also had the opportunity to work on several community-based murals. This has led me to create my own community-inclusive projects.

EF: Where do you create your artwork?

AH: I create most of my work in my apartment…a two bedroom I have converted into a studio shared with my partner Nicholas.

EF: What inspires your creations/where do you get your ideas?

AH: I like to examine power structures that influence actions and thinking. These structures are often linked to politics, the media, false barriers and our visual environment. My interest in this began on a visit to Berlin, Germany, where I witnessed massive buildings and sculptures. I felt very small and helpless around them. I thought about why these structures were built and how they emitted power and dominance because of their scale and placement. It helped me recognize similar “structures” existing around us that are less visible and more difficult to define.

EF: Does color play a distinct role in your artwork?

AH: Since most of my two dimensional work is with graphite and paper, color is only utilized as an accent in the work.

MURAL INVOLVEMENT:

EF: Describe your involvement in mural-making. Is this a solitary effort or collaborative?

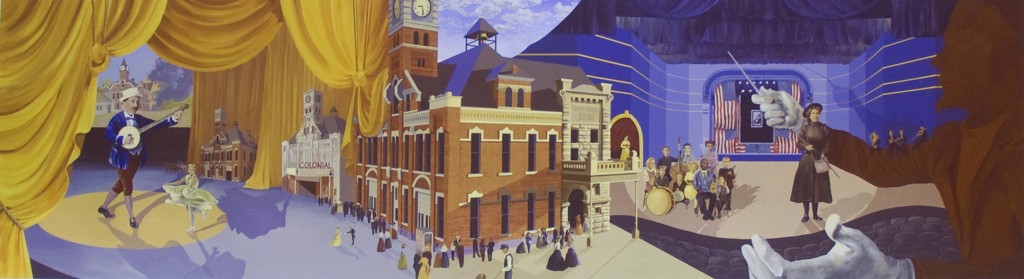

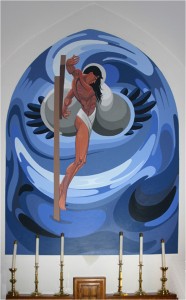

AH: I started creating murals in high-school and continued during undergraduate studies. I painted a lot of school mascots, sports teams, motorcycles and landscapes. My first mural collaboration was with my partner, Nicholas, for St. Paul’s Episcopalian church in Vermillion, SD. The painting, Indian Christ, was originally designed by a well-known Native American artist, Oscar Howe. The painting was designed for the church in Vermillion but was never made into a mural because of its sensitive content (the image of a Native American hanging on a cross). After Howe ‘s death, a new pastor found the painting and wanted the mural realized. That mural quickly became a crash course on color theory, as we tried to match the mural to painting as accurately as we could. Oscar Howe used over 20 different variations of blue in this piece! Our second mural project involved two murals for the newly renovated C.L. Hoover Opera House in Junction City, KS. These were the first original murals Nicholas and I created. Many lessons were learned on that project.

AH: I started creating murals in high-school and continued during undergraduate studies. I painted a lot of school mascots, sports teams, motorcycles and landscapes. My first mural collaboration was with my partner, Nicholas, for St. Paul’s Episcopalian church in Vermillion, SD. The painting, Indian Christ, was originally designed by a well-known Native American artist, Oscar Howe. The painting was designed for the church in Vermillion but was never made into a mural because of its sensitive content (the image of a Native American hanging on a cross). After Howe ‘s death, a new pastor found the painting and wanted the mural realized. That mural quickly became a crash course on color theory, as we tried to match the mural to painting as accurately as we could. Oscar Howe used over 20 different variations of blue in this piece! Our second mural project involved two murals for the newly renovated C.L. Hoover Opera House in Junction City, KS. These were the first original murals Nicholas and I created. Many lessons were learned on that project.

Our involvement with the Mid-America Arts Alliance’s Mural Project began in 2010. Dave Loewenstein needed an assistant for a mural in Tonkawa, OK. The story goes, he was passing through Junction City, saw our murals and contacted us to see if we would be his assistants. We hadn’t quite graduated from KU, but the week after Nicholas’ thesis show, we headed to Tonkawa, OK. During our time there we really fell in love with the town and began filming what would eventually become Called to Walls. We followed the project to Newton, KS, Joplin, MO, and Arkadelphia, AR. Currently we are in the process of editing the documentary film about our experiences on these projects, The film will shed light on the process of creating community based work and serve as a portrait of each community and compelling story.

LEARNING IS REMEMBERING:

EF: Explain your drawing series titled Learning is Remembering.

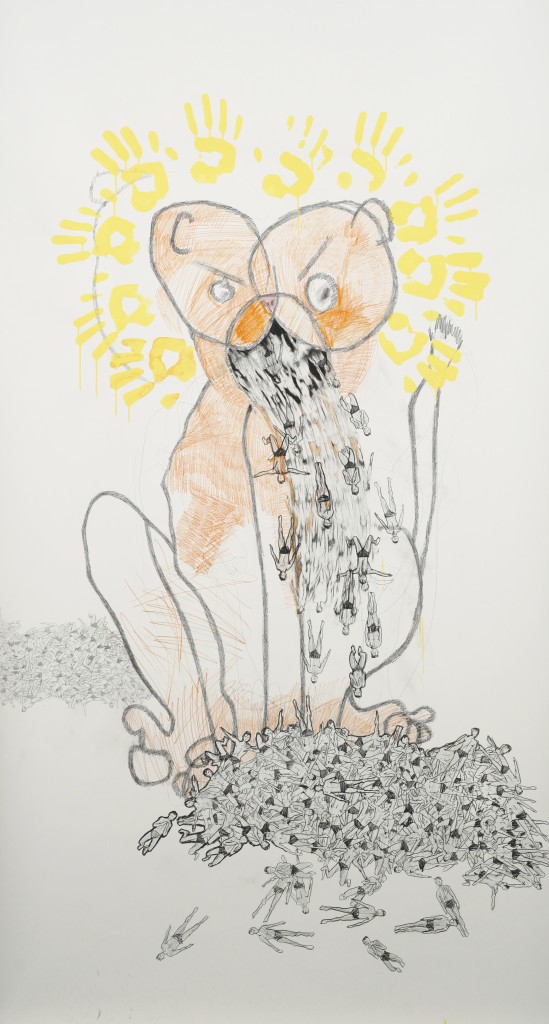

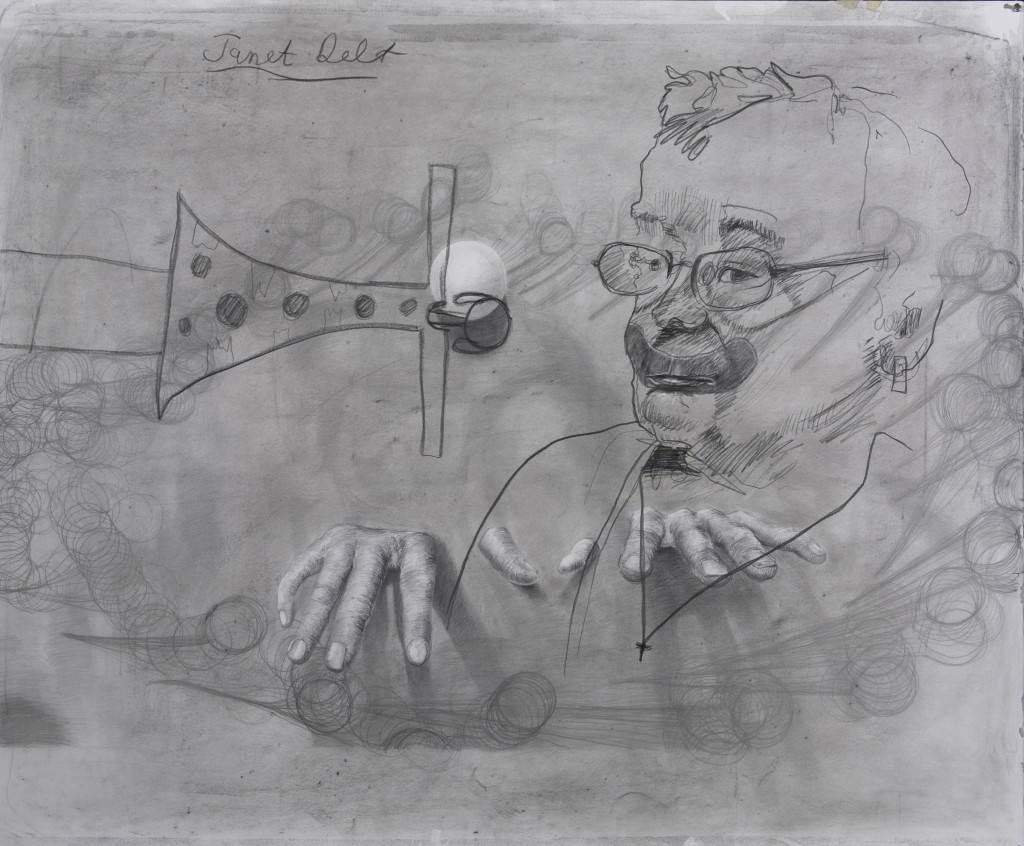

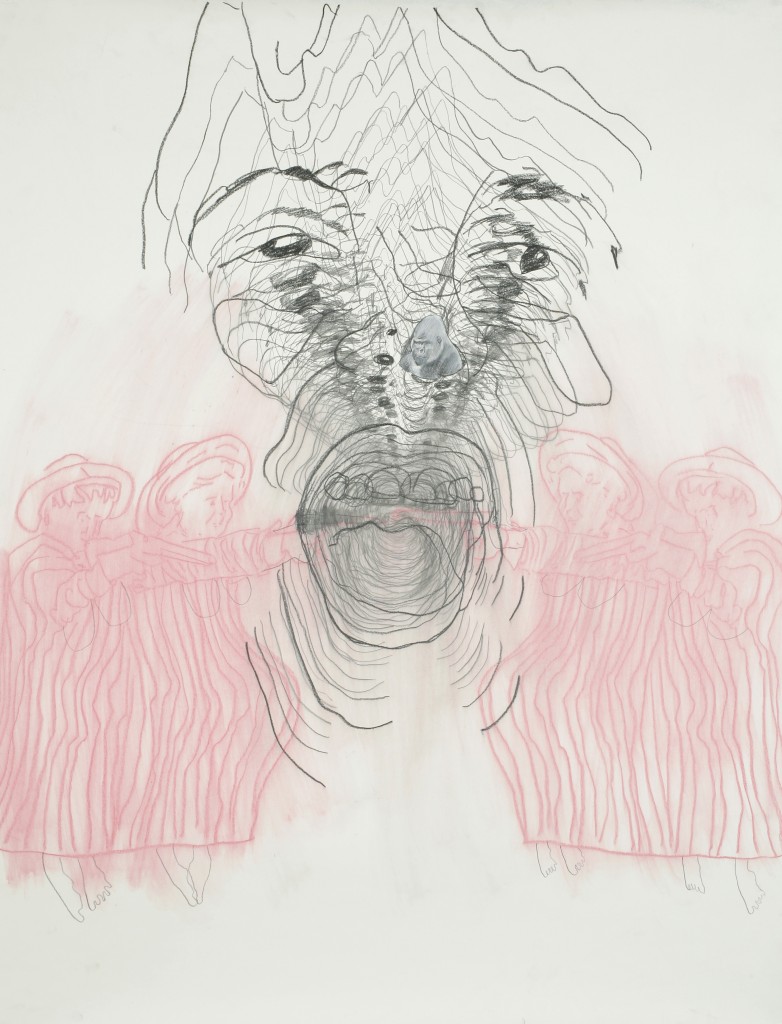

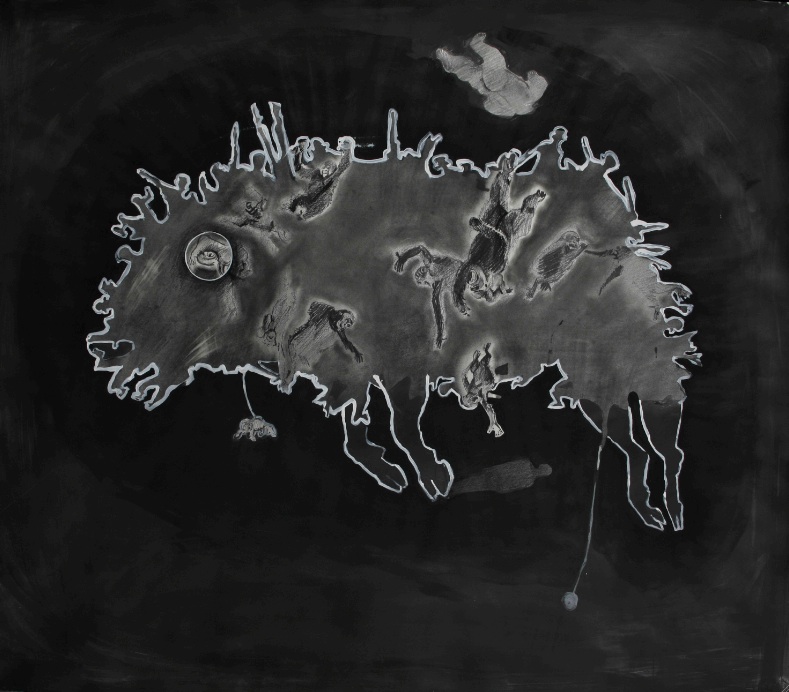

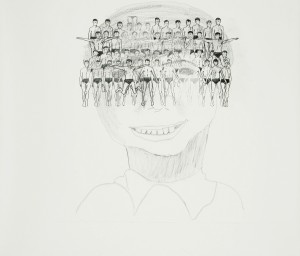

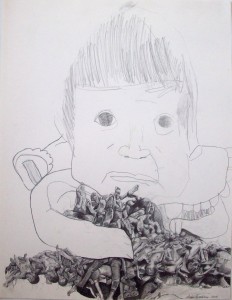

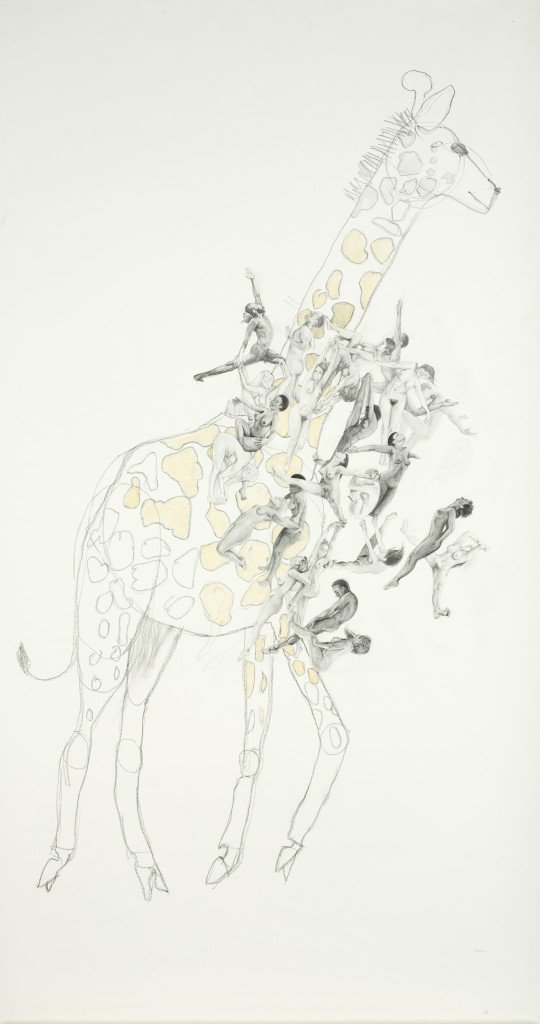

AH: Learning is Remembering is a body of work that assesses the value of innate knowledge and educated thinking. I combine line drawings from my childhood with learned and practiced modes of pictorial representation. By mixing the thoughts and styles of multiple time periods, I am layering and combining different levels of consciousness and types of motivation. The videos are extrapolations of childhood actions, representing different modes of understanding. The work expands the notion that the searching process propels creative thinking and action, and is transformative. Great knowledge and understanding is revealed through the process of creating and can be activated through no other form of learning/remembering. To create a group of seven drawings and the three accompanying videos took three months. I have continued to add drawings to this series and now have over 20. The drawings range in size. The largest is 8ft by 4ft and the smallest is 8in by 4in. I like to work on the larger drawings but practicalities such as framing, space and preservation create restrictions. I have been very lucky to have the help of Cotter Mitchell and Garret Brown to create frames large enough for this work.

EF: Why was it important for you to revisit these childhood drawings/scribblings?

AH: I was at a roadblock in my current work. I was trying to answer the question: why do I make drawings? So I began to look at my motivations as a child. This quest was inspired after reading a book by the neuroscientist, David Eagleman, Sum: Forty Tales of the Afterlife. Eagleman created forty different scenarios of the afterlife. In one story, he describes each person as existing at every stage in their life…as a one year old, a seven year old and so forth. I realized how much motivations and ideals change as we age. Each person lives as many distinct individuals while remaining contained in the same, ever-changing body.

EF: How does your artistic process now differ from your artistic process back then?

AH: As a child I loved to copy things and found it very difficult to express my own ideas in drawings. A lot of that has changed. I have more confidence in my own ideas and what I want to represent, as well as more control in drawing. I like to play around with different types of pictorial representation because of the unique thought processes they require.

EF: There is sparse use of color in these pieces. Why so little color and does it represent something?

AH: I use color as accent and very symbolically. It is something I utilize when unable to express with value. There are many different ways I accent certain characters within these drawings. Sometimes I end up just circling the part I want the viewer to notice. I haven’t done that for a while.

EF: What have you learned through remembering?

AH: I enjoy thinking and once read about learning this way. Everyone, at birth, contains all of the knowledge they need throughout their life. So when we think about learning, it’s not a process of packing information into our heads; rather it’s finding methods that allow us to access information that is already within.

There are many ways to access this knowledge. For me, I believe drawing is the most direct method.

EF: Why the inclusion of video? Is it essential to pair with these drawings?

AH: I think of drawing and video as different types of creative language. Part of my role as creator is to find a mode that best articulates an idea. Often a video begins as a drawing that seems incomplete. If I think the underlying idea is good, I know it must need a different representation. Some things are better as static images, while others should exist in a time based form. So far this approach has worked well for me.

THE STORY OF CHICKENS:

EF: The Story of Chickens generated local as well as national attention (both support and outrage). Share with our readers the projects conception, intentions, and modified execution.

AH: On our farm we raised animals as companions and for our own consumption. Life and death were visible elements. I have celebrated the births and mourned the deaths of many animals in my life. When I stepped away from the farm and from those relationships, I began to question the meat I was eating and where it came from. The answers led me to an awareness of contemporary farming methods and the conditions it creates for animals, humans, and the environment.

The story of chickens was designed to offer experiential knowledge. At a time when consumers are conveniently distanced from what they consume, the project set out to create proximity, familiarity and a responsibility between benefactor and consumed. In this case, people and chickens. The proposal: to introduce a mobile chicken coop into an urban environment. For one month people would be invited to help care for and tend a small flock of five chickens as the coop traveled to select public locations throughout the city. At the end of the project these chickens would be slaughtered by a local farmer and prepared for a community potluck the following day that would conclude with a conversation about our relationship with animals and the food we eat.

To fund the project I applied for a Rocket Grant through the Charlotte Street Foundation. It was accepted and the project proposal was posted to their webpage for a year. A month before the start of the project, a great number of people began to react, asking for alteration and even termination. Social media supported the conversation and soon the project generated national attention, revealing both support and disapproval. During the planning phase (and after public reaction to the project), I was approached by the city of Lawrence, KS and informed that it was illegal to kill the chickens within city limits. Because of this, the coop traveled around as planned but without it’s feathered residents.

The coop stood as a meeting place for citizens to talk about their relationship with animals and animals as food. It also served as a mirror of the veiled existence of the consumed and a symbol of our current relationship with the animals we eat.

I am extremely grateful to the Charlotte Street Foundation for supporting the project and to the members of the Percolator (where the project took place). The Percolator is a community run art space in Lawrence, KS. The people who organize the shows and run the space are amazing. They were extremely supportive of the project during every stage and constantly contributed their time, ideas, energy and support.

To promote a discussion on both perspectives, I invited individuals from the community to speak at the closing event. We shared food together and listened to many viewpoints about caring for chickens, humans relationship with animals, and eating animals. All while being surrounded by local artwork, poems, and films relating to the topic.

The project raises many questions, including the one that still remains for me: how does removing animals and the processes related to eating animals from our visual environment affect our relationship with the food we eat, our psyche, and our actions.

EF: How does art make you feel?

AH: Art makes me feel like there are things in the world that make sense.

EF: If you had to pick one of your pieces to best describe who you are as an artist, which one would it be and why?

EF: If you had to pick one of your pieces to best describe who you are as an artist, which one would it be and why?

AH: I would pick a video piece titled The Wall, one of the first digital videos I created. I wanted to create work that took me outside the studio and outside my comfort zone. The horse in this piece is surrounded by balloons. The balloons make up a false sort of boundary or fence representing my own psychological barriers and false containers.

When I return to this piece it is always relevant. I realize I am always walking towards the edge of what I know and understand through art, expanding my own boundaries of understanding, leading to new ideas.

EF: Do you plan on devoting your life to your artwork?

AH: This has been my intention for as long as I can remember. However, my definitions of art are constantly changing and broadening…so, yes. I think of art as a way of approaching issues through a medium. The mural project is a good example. The work is art but the paintings are collaborative, not belonging to any one artist. I could see my work evolving in many directions but it will always be art.

EF: On average, how long does it take you to finish a piece? A body of work?

AH: That depends on what is being created. When working on drawings, I often work on several at one time, with four or five hanging in my apartment to constantly consider. When not directly working on them, they live in my head. As a group they live with me, each one communicating to the other. I have an idea to begin, but by the time I finish, that idea has changed and evolved in the process. A series of five drawings may take a couple months to complete, while a single drawing might be finished in a couple days.

EF: What is your favorite piece of art/artist?

AH: Some of my favorites are Miranda July, Marina Abramovic, Nicholas Ward, and Allen Kaprow.

EF: What is your favorite book/author?

AH: In Persuasion Nation by George Saunders.

EF: What do you plan to do next with your art? Are you working on anything new?

AH: Right now I am working to complete the film Called to Walls, a poetic documentary on creating community-based work in the Midwest and within rural communities. In the film we are following lead artist Dave Loewenstein as he makes mural’s in several towns throughout Middle America. Also in the works is a new group of drawings and three short films that my partner Nicholas and I have shot but have yet to edit.

To see more of Amber’s art, visit: http://turtlesounds.blogspot.com/