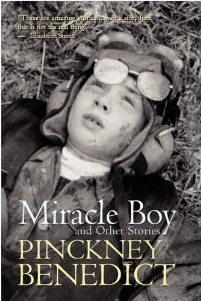

Pinckney Benedict is the author of three collections of short stories, his most recent being Miracle Boy and Other Stories (Press53, 2010) and also the Steinbeck-Award winning crime novel, The Dogs of God, published by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday. His first story collection, Town Smokes was published by (Ontario Review Press), followed by his collection, The Wrecking Yard (Nan A. Talese, 1992).

Pinckney’s stories have appeared in Esquire, StoryQuarterly, and the Ontario Review, to name a few, and he has also had stories published twice in the O. Henry Award series, four times in the New Stories from the South series, and three times in the Pushcart Prize series.

He is currently a full professor in the English Department at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois, and is also on the core faculty of the low-residency MFA program at Queens University of Charlotte in North Carolina. He has been a McGhee Writing Fellow at Davidson College in Davidson, North Carolina, and a Thurber House Fellow at the Ohio State University.

Pinckney graduated with a degree in English from Princeton University and earned an MFA from the University of Iowa. He is the recipient of such prizes as the Chicago Tribune’s Nelson Algren Short Story Award, a Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Literary Fellowship from the West Virginia Commission on the Arts, a Fiction Fellowship from the Illinois Arts Council, and a Michener Fellowship from the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa.

Derek Alger: it appears growing up in West Virginia was fertile ground for your imagination and consequent storytelling.

Pinckney Benedict: I grew up on my family’s dairy farm, which meant no neighbors and hence no neighbor children to play with, for the most part. Plus I was a pretty strange kid – had a wide vocabulary from constant reading and a lot of anger that made me deploy that vocabulary in pointed and unpleasant ways – so I didn’t have a lot of pals, particularly early in my life. So I was, more often than not, until the time I was eleven or twelve, my own playmate. Which generally suited me fine, because it meant that my games could be as fantastic as I wanted them to be, and my own part in them could be as grandiose as I liked, which was pretty grandiose. I grew up accustomed to creating my own imaginative universe.

And it could be a pretty grim place, that universe, built as it was out of my imagination, which is and always has been quite dark, and out of my reading, which was mostly ghost stories and classical myths and the incredibly creepy pages of ancient issues of Mad Magazine, and the world of the farm that surrounded me. The farm was capacious, and it could feel as though the whole population of the planet had gone away, or died, when you were out walking the fields alone. That it was just you and the bugs and an occasional cluster of cattle that stood there and stared at you like you were an unpleasant alien, their tails clumped with shit.

DA: Sounds like time for your imagination to kick in.

PB: So it was either make up stories and games that kept me entertained, or go batshit crazy. And that has been the pattern of my life, though my surroundings aren’t quite so Gothic these days: make up stories and games to try and keep sane.

So yes, it was beneficial to grow up there, in that it gave me a lot of fuel for my fiction – but it was pretty clear from early on that I wasn’t going to make much of a farmer. That’s always been my older brother’s thing, and I think everybody was pretty grateful when we recognized early on that my life wouldn’t be spent on the farm. Not as a farmer, anyway. I am not good with livestock (I don’t have the patience), and I tend to tear up machinery.

The fact that those stories I tell myself are written is only coincidental, as is the fact that I tell them to others, sometimes, when others care to read them, which is not often enough, in my opinion. If I’d had a movie camera, I might have made films, for instance. But what I had was words. My parents were both great readers – my dad read nonfiction and my mom read novels, by and large – and we had a wealth of books around the place. And not much in the way of television: two channels, three on a good day. There was a great love of language all around me, in Appalachia generally and specifically in my family. We played word games like Ghost, and we punned, and we argued, and we celebrated language. My grandfather used to say – this was the kind of thing we loved to repeat to each other around the dinner table – after he had eaten supper, my mother’s father would push himself back from the table and announce, “I have et a sufficiency. More would be a superfluity.” Which is absolutely precise, and absolutely hilarious.

DA: You were fortunate to attend The Hill School in Pennsylvania.

PB: I was a “five year boy” at The Hill, from eighth grade (which was called Second Form) through high school graduation. There are guys who commit manslaughter that don’t get five years in a place that hard. It was clear pretty early on, when I was attending public school in Greenbrier County, my home county, that I was going to need something beyond the scholastic challenges that West Virginia was going to be able to offer. The last thing you want is a smart, angry, bored kid on a farm. Send him away! To a place where being smart is – at least in theory – a boon rather than a problem, and where anger can get him through the day, and where he is working too hard ever to be bored.

DA: Was it a good move?

PB: I was wildly homesick for the first couple of years, after which I got to know the place well enough that it became a kind of ersatz home to me. This was an era when the school was all-male, and in serious decline, from which it seems to have made an almost complete recovery. Drunken, abusive teachers (“masters” as we called them), crumbling buildings, thuggish athletes, rampant drug usage. Also brilliant teachers, hugely intelligent men dedicated to education with a fierceness that it’s hard to imagine you could find anywhere today, at any price. And great classmates and friends, whose wit and genius for subtle and not-so-subtle resistance in the face of a patently inhumane institution sometimes still makes me grin and laugh today. Some of those people, teachers and classmates both, I still know. There’s a kinship that comes with being stringently educated in that way that’s not easily thrown off.

So it was a tough five years, but not without its rewards. After The Hill, college was easy. There were girls there! And you hardly had to know any facts at all, nor really to read any of the books that they asked you to read, so long as you knew how to temporize with the right sort of pseudo-intellectual language, to respond with a kind of smarmy, slightly bored, breezily sardonic, smirking skepticism.

Plus, now anytime I look around me and find I’m not living in an aging, smelly gulag of a dorm, I get a smile on my face. Like hitting yourself in the head with a hammer: five years at The Hill make me a happy man, because I don’t ever have to do that again. Though I do, again and again, in my dreams. At least once a week I dream I’m back in that foul place, unable somehow to graduate. I imagine that’s what ghosts must feel like.

The great blessing of The Hill was its classics department. I took a lot of Latin and a not inconsiderable amount of Greek, and again in those classes I was in a place where language mattered, where language had primacy. I could handle language, though most of the rest of the world defied my control or understanding. And the stories were great! The classical world is a magnificent thing for a young man to spend his time contemplating. Like the Old Testament, it’s replete with glorious slaughter and Technicolor smut. The humor is bawdy and the spilled blood is real. It all comes to you in this wonderful, precise language, language that’s wielded like a weapon. Couldn’t get enough of that.

My older brother also studied classics at The Hill, and he became a Greek major at Amherst. My dad was philosophical about the virtues of a liberal education. He didn’t see it as training for a job, which I suppose is the current wisdom. He saw it as the foundation for the life of the mind, which could take place independent of one’s circumstances. I remember his saying, “Greek gives you something to think about while you milk the cows.”

DA: Going to Princeton University was a turning point for you.

PB: Well, the creative writing classes were a turning point. The rest of the place, I frankly didn’t care much about. Princeton seemed to me a place – still seems to me to be, when I get the occasional begging letter from them, which I discard with a nasty frisson of pleasure – that’s extremely pleased with itself. Most of the faculty, and most of my classmates, seemed the same way. Happy to be Princetonian! And no doubt they were, and are, right to be happy, and to be Princetonian is in fact a wonderful thing. But I didn’t get it. They all seemed to me to be very smart and accomplished in their fields, and witty – in that nihilistic fashion that was then the rage at top-flight universities and no doubt still is – but almost nobody (outside of the sciences, anyway) seemed to me to be doing much of anything.

At 185 Nassau, which was where the writing program was housed, and which was (properly, it turns out) quite separate from the rest of the university, people were doing things. They were producing work that was being widely read. They were working. And the greatest piece of good fortune that awaited me at Princeton was my apprenticeship – not formally, but certainly spiritually – to Joyce Carol Oates, who was on the permanent faculty there. I worked with her all four years I was at the place, wrote my thesis for her, did everything I could during my time there and after to produce a fiction that she found satisfactory. She and her husband, the irreplaceable Ray Smith (whom I still miss), published my first story and my first collection of fiction, a book titled Town Smokes.

DA: Sounds like a great experience, at least the writing courses.

PB: Think of the writers I got to meet at Princeton: JCO. Russell Banks. Eudora Welty. Robert Stone. I didn’t know who they were in the world, not in any real way, until after I had graduated. It didn’t seem extraordinary to me at all – this makes me laugh now, that it seemed natural to me – that such folks should spend time with the likes of me, should read my work, should pay any attention to me at all. I was arrogant enough, and ignorant enough (qualities I still possess plentifully) to think that such a thing was normal. And they were so humble, you wouldn’t know they were celebrated across the country and around the world. On the odd occasion when I happen to meet famous writers now, at AWP and elsewhere, it amuses me deeply, how hard they often seem to be working at being famous. They seem to be straining to radiate famousness from their pores or something. They seem desperate to be recognized and loved. It’s grotesque and sad, particularly when you consider that being famous, in the context of being a “literary” writer, means you’re known by about as many people as, say, the host of a moderately successful children’s television show in New Zealand. And these giants among whom I came of age, they were to all appearances just unaffectedly generous people who wanted to help me with my work, and who wanted to help the students around me with their work. It was an extraordinary time. Golden.

I adored those classes. I lived for them and regretted that they only met once a week. I loved my fellow writing students and their fiction. I remember to this day stories that I read in those workshops that impressed me, stories by Stephen Cope and Charles Wohlforth and Doug Century and Lance Wilcox, great fiction written by folks who were extremely talented and daring, even that young. The criticism they gave me was invaluable: it took my work seriously, it took me seriously, and it wasn’t tainted by the gruesome species of competition that you find in most writing programs. It was criticism that was actually intended to make the writing better, and to make the writer better, rather than being simply devised to dishearten or destroy a possible rival. At the time, I had no idea how rare such an atmosphere of caring seriousness might be.

DA: And then off to Iowa Writers’ Worksop.

PB: Bingo. See above: gruesome species of competition. Famous people yearning to be recognized, and hoping to seduce or, better yet, be seduced by the more attractive graduate students. Journeyman writers yearning, not to become better writers, but to become famous writers themselves. I spent most of my time out there alone, away from other writers. It would have broken me, that isolation in that deeply unfriendly place, I think, except that my first book was already in process. It came out in May of my first year at Iowa. I also won a thing called the Nelson Algren Award from the Chicago Tribune right around the time I got to Iowa. Those two successes, modest as they might have been, kept me from believing the low opinions that pretty much everybody in workshops at Iowa expressed about my work on a continuing basis.

DA: Not bad, Eudora Welty’s comment on Town Smokes was, “we are beyond question in the presence of a strong talent.”

PB: A lovely woman. Gracious, unassuming, kind enough to write that about my work when, clearly, she had nothing to gain from it. When I think that the writer of “A Worn Path” and “Petrified Man” laid eyes on my work and wasn’t mortified, and was in fact moved to be kind about it – words fail me.

Her work, along with the work of some others, Robertson Davies chief among them, means a great deal to me. I recall reading in Davies that he believed writers were properly moralists: not that they dictated morals, but that they observed the world clearly and reported in a truthful way what they observed. That truthful observation is a moral act, and that you don’t owe anything more than that to your readers, because there isn’t anything more than that. Nor can you do anything less and still be doing the work you are meant to do.

DA: What came after Iowa?

PB: A great year, a position as writer-in-residence at The Hill School. Back at my alma mater, which had moderated its more gloomy and grotesque aspects by that time and seemed to be in the process of becoming a modern institution. It was the place where I learned to teach. Before that year, I had never seriously considered becoming a teacher. When I was there, I thought of the teachers whom I had known, great teachers throughout my life, and of Joyce Carol Oates, who managed simultaneously to be a brilliant, prolific artist and a selfless teacher. And I realized that (how dumb to figure this out only then, after having been influenced by fine teachers my whole life?) teaching should be a large, perhaps the largest, part of my life. That, if I could do it, I should.

DA: Two major developments occurred after that year.

PB: I took a job teaching creative writing at Oberlin. My colleagues in the writing program there were a lovely married couple named Diane Vreuls and Stuart Friebert. They were both very tall, like kindly giants, and I remember, on my first day, being shown where the extra key to the office was kept: way up high on top of a doorsill, in a place that I – I am not a tall man, I am of average height – would never be able to reach without a ladder. And it occurred to me that this was a signal that Oberlin was not for me. As it turned out not to be. I was there for two years.

Then I signed a contract for two books with Nan Talese, who had her own imprint at Doubleday, and the money from that contract allowed me to leave Ohio and go back to West Virginia. I was married by that time, and my wife, Laura, and I lived on my family’s farm while we wrote – she is also a writer, of thrillers – and started a family.

DA: What was your experience working with Nan Talese like?

PB: A thoroughly lovely human being. Old school, in the best possible way. If everybody in publishing were like her, we would not now be hurtling into the abyss of universal illiteracy and disinterest in all things written. Which we’ve very honestly earned, by the way. Jesus, so many books are just so precious and excruciatingly boring! No wonder people don’t read. I’d rather pick my toes than read most of what the New York Times reviews approvingly.

DA: Your stories may be based on the specifics of your Appalachian Mountains upbringing, but your characters are always dealing with universal themes of humanity, whether they know it or not.

PB: I’m flattered that you think so. I’d like to believe that, while the setting of my fiction is always absolutely specific to me personally, I’m doing more than writing a regionally-relevant fiction. It may also be that, if my work possesses universal qualities, it’s because I’m constantly cadging my material from much greater writers and storytellers and simply rendering it in terms of my Appalachian background. In my first book, there’s “Booze,” which is about a monstrous white boar that terrorizes a family farm: that’s just Moby-Dick writ small. In my second collection, there’s “Horton’s Ape,” which is my retelling of King Kong, but with an escaped baboon instead of a giant gorilla, and a cactus instead of the Empire State Building. And in Miracle Boy, my most recent collection, I’m ripping off classic science fiction, Ovid, the golem legend, and a whole host of other, better sources.

DA: Don’t underestimate yourself.

PB: Maybe I would do well to say I’m paying homage. That sounds less wicked, I suppose, though I think we would benefit significantly as writers if we were to lose our fetishistic interest in “originality.” “The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” Ecclesiastes says it all, right? If we would simply acknowledge the models from which we work, the paradigms we employ, the influences we feel, then we’d produce better, more honest work, and people could trace those influences all the way back to the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the journey would be fun and educational. Every work of fiction would be this interesting tributary off the great river of Narrative, that leads all the way back to humanity’s beginnings and the fountainhead of Story. Instead, we like to pretend, or even imagine, if we can fool ourselves, that we’re doing something new and different, and that others in whom we recognize influence are somehow deficient in imagination or creative energy.

You could take any great story from Mesopotamia, set it in Manhattan, or Seneca County (the fictional region in which I generally set my work, a stand-in for my native Greenbrier County), or on Mars, and it would work. It would still be a great story. And it would communicate universally.

DA: You attended a positive life changing writers’ conference in Kentucky in 1989?

PB: Ah, yes. The Appalachian Writers’ Conference, at the Hindman Settlement School, “at the forks of the Troublesome Creek,” as they say there. It’s a wonderful, long-established conference. Sad to say, Mike Mullins, who ran it for decades, died too young not long ago. Hard to imagine the place without him. And the great James Still, of River of Earthfame, was living in a cabin on the grounds at the time. He came and taught a session of the workshop I was in charge of. It was pretty exciting, because I didn’t know anything about it beforehand. Just, there he was, James Still, this Kentucky colossus, looking slightly drunk, slightly deranged, and he went to the front of my class – I’d prepared notes on some aspect of craft, was getting ready to teach – and he held forth for a couple of hours, reciting from his own work, from memory, and expatiating on any number of subjects, some literary, some not; and then he ran out of words at a certain point and just kind of swam away again.

But all of that pales to insignificance, because one of the attendees at that year’s conference – the only attendee, in my eyes – was a young blonde woman with whom I became immediately obsessed, and whom I began pursuing. She didn’t, as any sensible person would have, swear out some kind of court order against my attentions. Instead, she put up with me and eventually even married me.

Her name is Laura Benedict (nee Philpot), and she’s the author of three thrillers: the novels Isabella Moon, Calling Mister Lonelyhearts, and, most recently, Devil’s Oven. Scary books. You can see pictures of her and read all about her and her work at laurabenedict.com. She’s super-hot.

DA: Your novel, Dogs of God, has been praised as an intense, emotion packed thriller set in contemporary, rural West Virginia.

PB: That’s nice to hear. I set out to write a potboiler, a simple page-turner about bare-knuckle fighters and dope growers. The New York Times review said something along the lines of “One fears for the sanity of the writer who dared to look the demons in the eye.” I figured, as a writer, if readers were worried about my sanity, I must be doing something right. Every book that I really like, I think to myself at some point, “Damn, that so-and-so had to be crazy, to imagine something like that. To invite that shit in, not just for a brief visit, but to dwell in the writer’s interior long-term.” Think of Patricia Highsmith and Edith’s Diary, which is one of the few books in the world I’ve ever had to put away because it was too revelatory, too raw and distressing for me to read; and yet, when I’ve returned to it, I’ve realized that it is – because of that quality, not in spite of it – very great. Its horror was not circumstantial, not based in plot or melodrama. Its horror derives from the character of Edith, yes, but also from someplace much deeper than the character: from the world in which the character dwells, which is ultimately the mind, or rather maybe the spirit, of the writer. This is what I think of as the allegory of self, and it’s vital to fiction.

Or think of, say, Shirley Jackson, whose work I admire as deeply as anybody’s I can think of. You can’t read her work – not seriously, deeply – without understanding that, beneath the exterior of high literary intelligence and ingenious plotting, something is desperately wrong. Not just with the people in the book, which is a commonplace quality; but with the writer. She’s bent, and she’s coping with how badly she’s twisted by telling the stories she’s telling. It’s a survival mechanism, not a way of appearing attractive or noble or dateable.

(Unfortunately, it’s not really a great survival mechanism, which is why many writers do not in fact survive, or die psychically and morally and artistically even if they continue to breathe and eat and so on.) That’s what makes literature, real literature, so tough to look at sometimes. And writers would rather be glossy and attractive, easy to look at, than to show you what’s wrong with them.

Who wouldn’t? No sane person approaches another person, particularly a stranger, but even an intimate, crying, “Look at my wounds! Look at the terrible things I think about! I think about them all day! I can’t think about anything else!” But that’s what writers do, when we’re doing it right, when we can deny that (very natural) impulse to want to look good and happy and sane.

DA: You were offered an unexpected chance to write a screenplay.

PB: A director and producer in Toronto were putting together an adaptation of a 1964 novel by John Buell. It’s titled Four Days, and it’s about a kid whose brother (we made him the kid’s father in the movie) dies in a robbery, but manages to pass the money off to his kid, who doesn’t know he’s died. The kid goes off on a series of adventures in the four days (thus the title) after the brother’s death. The director had recently read Dogs of God and liked it, and so, out of the blue, he called me up and asked me if I’d like to try my hand at writing a screenplay.

Sure, says I, never having done such a thing before but liking the dough. I downloaded some screenplays from the internet, to see what one looked like, and I bought some screenwriting software to take care of the formatting for me, and I crafted a fifteen-page scene – which is still in the movie, the one where the female lead shows her boobs to the fourteen-year-old male lead: see above, where I talk about revealing the scenarios that run relentlessly in your head – that they used to raise money for the production.

We got some excellent actors: Colm Meaney, the Irish guy; William Forsythe, the wonderful character actor who’s been in a million films; Lolita Davidovich, “the thinking man’s bombshell,” as somebody called her; Kevin Zegers, who at that point had been in all the Air Bud movies and who wanted, I guess, to shed his Disney-kid image by gazing longingly at Lolita Davidovich’s heaving bosom.

It was a crime film, a caper film, which was a lot of fun to write. This kid, who has lived an isolated and not-very-enjoyable life, ends up with a bag full of money and a beautiful, wanton woman for a companion. The female character was made up out of whole cloth; someone like her appears for about a page in the novel, but that did not fit my fantasy, nor did it fit the producer’s desire to have a strong female part in the film.

DA: Sounds like a positive adaption for the screenplay.

PB: I got along well with the director and producer, so I got to spend a good bit of time on the set during shooting, in Montreal and in an area of Canada called Trois Rivieres, which was quite beautiful and remote. I got to go to strip bars with Forsythe, whom everybody knew and loved, a big princely bear of a guy, and to drink with Meaney, who was charmingly morose and intimidatingly smart. Whenever Colm was approached by someone who recognized him, you could tell that he was hoping they’d say, “Hey, you’re that guy from The Commitments or from The Snapper, but they always came up with Star Trek, in which he played Chief Miles O’Brien. I guess that would be hard to take, if you’re of a certain temperament. Myself, I think I could laugh all the way to the bank, as they say.

And that gig got me other gigs writing screenplays, though Four Days is the only one that has so far seen production. I’ve written a story adaptation for American Zoetrope, written the adaptation of my own novel for a British production company, written a historical script for the Canadian production company that did Four Days. It’s fun and it pays well, but in the end you feel like, if the film isn’t produced, you’ve just written a well-remunerated novella for the world’s smallest audience – even smaller than the audience for most literary fiction, which as we all know is vanishingly small. It’s odd.

DA: Where could one see Four Days?

PB: If folks want to see Four Days, it was available on Netflix streaming, the last I looked. It’s slower-moving than I would have liked, but there are some good performances. And Lolita Davidovich is naked in it. Kevin Zegers too, nearly.

DA: How did the idea for the Surreal South anthology come about?

PB: My wife and I are both addicted to horror fiction and to stories of the grotesque, and we’d long wanted to do an anthology together. Press53, which publishes the series – in its third edition now, as of late 2011 – is in North Carolina, and we liked the word “surreal,” so we came up with the (to our ears anyway) euphonious phrase “surreal south.” We pledged to publish only work that we ourselves loved, that we would like to read. Too many folks, I think, try to collect, or even to write, work that they imagine others would be interested in. If folks would just do the work that they themselves love, we’d all be a lot better off. We also wanted to forge a kind of rapprochement between the world of “literary” fiction (which I inhabit, in theory) and “genre” fiction (which, again in theory, she inhabits), because neither of us understands the divide – often quite acrimonious, particularly in the academy – between those two things. We like good writing, and we like good plots, and we like them together, all at the same time. And we particularly like stories about ghosts and monsters. Who doesn’t?

We’ve been really lucky in the writers who have been willing to let us use their work. Ben Percy, Dan Woodrell, JCO, Robert Olen Butler, the divine Julianna Baggott, folks like that. It’s been our intention to publish, along with these better known quantities, the work of writers who are at the very beginnings of their careers, or who are established but not as well known as we think they ought to be. We’re extremely proud of the work we’ve included that’s a writer’s first published story, or very nearly their first. That’s a great feeling, to hold up the work of someone new, to put it beside the work of an old pro, to see it hold its own there.

DA: You’re a fan of the writer Daniel Woodrell.

PB: “Fan” is probably putting it too mildly. Acolyte. Proselyte. I wrote a fawning essay as the foreword to the recent reissue of his novel Give Us a Kiss, which I reviewed for the Washington Post when it first came out. We’re also friends, which is incredibly lucky for me. I mentioned humble writers above, when I was talking about Princeton. Dan is one of that kind. Here’s this guy who has been doing sterling work for years, for decades, achieving what he’s achieved by his own merits, championed by no gods or heroes of the literary world, just telling good story after good story.

He’s very much his own man, which I admire. Lean years and fat years, and it’s always the same high-quality work coming out of Howl County. Contemporary crime or historical fiction, always the same great stuff. And now he’s in a fat time that looks likely to last, and all you can say is, “Outstanding.” I’d be perfectly content to resent him with the same cold fury-born-of-envy that I reserve for other wildly successful people whom I know, but I just can’t do it. He’s a loveable joker, and he deserves every bit of the praise and baksheesh that’s coming his way now. It’s overdue.

Not to rag on Iowa, but, you know, to rag on Iowa a little bit: I recall Woodrell telling me once that he was “ranked tied for last in my class and least deserving of any encouragement from among all the assembled young scribes.” Ha! Could they have got it more wrong?

DA: Tell us how the Tinker Mountain Writers’ Workshop came about?

PB: TMWW is an annual writers’ conference that’s held on the campus of Hollins University in Roanoke, VA, every summer. This coming year it will be held from June 9 – 14. Check it out at http://www.hollins.edu/summerprograms/tmww/index.shtml.

I am, along with Fred Leebron, my esteemed colleague from the Queens University of Charlotte low-residency MFA program, one of the founders and original directors of the conference, though now I just lead workshops. Hollins is an incredibly beautiful environment in which to write and to learn about writing, and Fred and I designed the conference to be as much fun as it’s possible to have while still busting your ass and getting your mind right.

DA: You’ve come a long way from the dairy farm of your childhood.

PB: From a certain perspective, I can see what you mean. I’m a full professor in an excellent creative writing program at a good solid Midwestern research school. I’m married to a woman who is much smarter and more beautiful than I could ever deserve and – though I generally dislike children – my own kids are so delightful and rewarding that I only occasionally considered smothering them when they were little enough to smother conveniently. Now, of course, they are much too big and strong for that, and too fast for their fat old man to catch. I am very seldom alone, and never in the way I was when I was a boy.

But all I have to do, all these years since leaving, is close my eyes for a second, and I’m back there again. Back in those fragrant, abandoned fields. Back in the shadow of those shaggy, dispassionate ridges. Back in those dank, mossy woods, where the light reaches the forest floor in golden shafts that make you want to cry for the beauty of them, and for their intangibility. So yes: a long way and not very far at all.