Pablo Medina is a critically acclaimed poet and novelist whose most recent novel, Cubop City Blues, was published earlier this year by Grove Press. At the age of 12, Medina and his family moved from Cuba to New York City.

Medina is the author of twelve books, including the newest translation of Federico Lorca’s Poet in New York, co-translated with Mark Statman. He has written three previous novels, six poetry collections, which includes The Floating Island and The Man Who Wrote on Water, and a memoir, Exiled Memories: A Cuban Childhood.

A former president of the AWP (Associated Writers and Writing Programs), Medina has been the recipient of grants from the Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest Fund, the National Endowments of the Arts, and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Medina previously taught undergraduate fiction and poetry writing, as well as a graduate literature course titled “Literature and Democracy,” at The New School in Manhattan. He currently lives in Boston and teaches at Emerson College.

Derek Alger: We can’t start off without noting you lived in Havana, Cuba until the age of 12 and then moved with your family to New York City.

Pablo Medina: I arrived in New York in the middle of a snowstorm. It was a magical experience that would color (if I may use that word in the context of snow) much of my initial reaction to the city and many of my subsequent experiences in the United States.

I could never disengage with my background and my upbringing. In New York our household was exclusively Cuban. My mother, at least initially, spoke no English. Many of our relatives who came to stay with us for short or extended periods of time as they settled in the new country were, of course, Cuban, and spoke that very rich and quirky variety of Castilian spoken on the island. Our apartment itself became an island, surrounded on all sides by a sea of English, New York English to be exact.

DA: The image of home as a “Floating Island,” which, in fact, is the title of one of your poetry collections, seems prevalent in your view of life.

PM: Yes, everywhere I have lived I have been an island, with no apologies to John Donne. Writing, too, induces that feeling. After a few hours sitting at my desk, I find myself surrounded by language on all sides.

DA: You and your father both spoke English when you came to New York and he worked for a Spanish soap company.

PM: Yes, a soap company. Soap in the tropics is almost as important as food, and more immediately important than books. Two of the great failures of the revolution is that it failed to provide people with soap and books, unless they were Marxist books of which there are plenty but nobody reads them anymore, if they ever did. Marxist soap, on the other hand, is an oxymoronic phrase. The proletariat is best when unwashed.

DA: How did you feel upon arriving in New York?

PM: I have said elsewhere that I was intoxicated with the physicality of New York, as I was with the physicality of Havana, though Havana was, when I left it, much more beautiful than the Big Apple. Physicality, however, goes beyond mere beauty. Havana was not majestic, not in the way NY was (and still is).

DA: You found a home at the library.

PM: The Public Library proved to be a refuge. In the cold winter afternoons when I couldn’t be outside, I went to the library and there read to my heart’s content and my mind’s content. At around age 14 the NY Public Library received a strong challenge from the porn book stores and movie theaters in the Times Square area. The titillation of porn, however, is not nearly as long-lasting as the excitement of literature. Both provided plenty of fodder for my dreams, some wet, most dry.

I learned New York English as a function of survival. The bookish English I learned in school in Cuba would not suffice. Besides, I felt that the diction of Mark Twain was much more eloquent than that of Edgar Allan Poe. Huck Finn’s voice, for example, was lively and engaging and did more for me than much of the 19th century literature I’d read. At the age of 16 a friend lent me a copy of Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn. Wow! That was street lingo taken to the bottom of hell and brought back up dripping with salaciousness. It was also very graphically sexual, thus irresistibly conjoining my two interests at the time.

I will always defend libraries, though I don’t often go to them any more, as I prefer to buy my books. The idea of a book being due disturbs me. Some books may take me a year to read. Besides, you can’t scribble in the margins of a library book and I’m a notorious scribbler. I could say similar things about the Priapic consequences of porn shops, but let’s not go there right now.

DA: Reading helped introduce you to American culture.

PM: Yes, books showed me the way into and around North American culture, from The Scarlet Letter to On the Road. I have the disturbing impression that that has changed. Since people don’t much read these days, they are not exposed to those monuments of culture. What cultural understanding does the internet provide? That’s not a rhetorical question. I would like to know. It doesn’t take a great deal of literary study to trace a line between the two books I mentioned above. You could do the same with movies, another marvelous product of American culture. The internet is a big question mark.

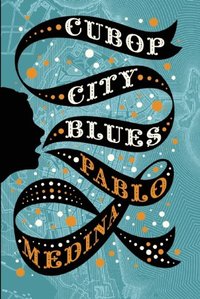

DA: Your recent novel, Cubop City Blues, clearly demonstrates you can write a creative lyrical narrative with interesting characters.

PM: That was the idea. Borges said that stories are about situations; novels are about characters. Cubop City Blues is about characters as they are embodied in voice. In the end it’s about the author’s character, as all novels are. The main character in CCB doesn’t need to overcome his blindness, he needs to overcome his enclosure, his islandness, if you will. And he does or begins to, aided by music.

DA: Publishers’ Weekly called Cubop City Blues “A haunting love letter to New York.”

PM: It is that, though I wasn’t necessarily writing it as a love letter. Love letters are of two types: the one you write when you’re trying to get someone in bed; the other when you’re trying to get them back to bed. Right around now I feel the love letter analogy falling apart. To quote the tee-shirt, “I love NY.” But it’s pretty difficult to write a love letter to a city, let alone go to bed with it. I think it’s easier to stick a knife into it. I mean that metaphorically, of course, as does CCB.

DA: Did you think of yourself as a writer from an early age?

PM: I’m glad you said “early” rather than “earlier.” That would make me a dinosaur. I was a reader from an early age, and there’s nothing closer to a writer than a reader.

DA: You first began writing poetry.

PM: Yes, I started writing poetry. I am still doing so and, if Cubop City Blues is any indication, poetry and prose are blending in my work. I like that very much. I published my first collection of poems, Pork Rind and Cuban Songs, in 1975 and then didn’t publish again until 1990, when Arching into the Afterlife, another poetry book, and Exiled Memories: A Cuban Childhood, my memoir, came out.

DA: Tell us a bit about Exiled Memories.

PM: Exiled Memories was an important work for me. On a writerly level it showed me I could write a sustained piece of prose. It was a prelude, if you will, to Marks of Birth, my first novel. On a personal level it liberated me from all the stories I’d been carrying around inside of me. They were wonderful stories about things I had experienced as a boy in Cuba and stories that had been told to me by my elders, but they were holding me back in that my imagination was trapped in their web. It was not nostalgia for a lost way of life, exactly. It was like being in a merry-go-round in which the only clarity was offered by those experiences—the experiences of being Cuban during a very interesting period in history. Let’s say I was held captive by them. Once I wrote them down, however, those stories and experiences released their grasp on me.

DA: What was it like when you finally had the opportunity to return to Cuba in 1999?

PM: My return to Havana in 1999 was complicated. I had prepared myself emotionally and had even brought my son with me as a shield against the emotional trauma such a return might bring. But even with him next to me, the trip was traumatic. The image I held in my mind of Havana (built mostly from memories of my life there before 1960) was still there, except that it was in ruins. Returning to Cuba was like returning to the ruins of my memory. It was a liberating nine days, but painful as well. The Cuba I belonged to was not the actual one but the one that was in my mind—a Cuba built of memories. The Floating Island was rearing up its head once again.

I had a draft of The Return of Felix Nogara before I myself returned to Cuba, which I had to rewrite completely after my experiences there in 1999.

DA: The Return of Felix Nogara tells the story of an exile from his homeland as a young teen and his return to the country of his birth 38 years later, with a cab driver as a major character.

PM: The cab driver acted as a guide and a foil, a sort of Sancho Panza who keeps correcting Felix’s skewed vision of things. In the end Felix marries the cab driver’s daughter, Luz, and winds up being a cab driver himself. People think the end of that book is a real tragedy. But I don’t think it is. Felix does achieve a stable existence in his marriage and new profession. It’s not a bad perch from which he can wait for death. We should all be so lucky.

DA: Your next novel, The Cigar Roller, also delivers with another fascinating protagonist.

PM: The Cigar Roller was born out of my interest in Ybor City, the planned community that grew around the cigar industry in Tampa, Florida, beginning in the 1880s. At first I thought I should write a history of that community, given how closely tied it was to Cuba and Cuban culture, but I am not a historian and so history gave way to fiction. Amadeo Terra is a failed human being (aren’t we all?) who comes to terms with his failures as he lies paralyzed in a rest home waiting for death. There is nothing for him to do but to examine his life, which he does, colored by his current surroundings, the rest home, and the characters who inhabit that place.

DA: Perhaps you could tell us a bit about your bilingual approach to poetry.

PM: I speak with forked tongue. I write with forked pen. It was an accident of biography and geography that I wound up bilingual. I can write poetry and essays in both languages; fiction comes mostly in English, though I found myself writing whole chapters of The Cigar Roller and Cubop City Blues in Spanish then translating them into English. Now I am engaged in writing Spanish and bilingual poems.

Language is the vehicle through which I define my identity. That much is true. But my identity is nothing unless I perceive it as such and then articulate it, give voice to it. I’ve been reading Husserl lately, can’t you tell? Identity is fluid and determined as much by circumstance as by anything else. Heraclitus, Ortega y Gasset—they both come into play. In Cubop City Blues, language allows the Storyteller to make his way in the world.

DA: Some might be surprised what you first studied in college.

PM: Biology. Why? It was not the pure science that I liked. It was the impure science. I didn’t know then that biology is chemistry, and I was less interested in chemistry than I was in creepy, crawly things. My biology teachers did not appreciate that. Rightly so.

DA: So you switched to studying literature.

PM: My interest in literature had to do with my interests as a reader and a writer. I was not interested in being a literary critic, as was the vogue then for literature majors, or being a theorist, as is the vogue now.

DA: You’ve earned a living teaching.

PM: I have made my living by teaching. I’ve taught in many situations and circumstances: high school, community centers. I’ve done poetry in the schools, I’ve taught in prisons, in colleges and universities. Teaching taught me grammar and it structured my life. In order to write around my teaching, especially when I taught high school and community college, I had to work around my job. I built very elaborate schedules for myself, blocking off writing times around teaching and taking care of my son. Fortunately, I don’t have to do that any more. I write in the mornings, I teach at night. My son is fully grown.

I got to love teaching as a function of my engagement with my writing. And saying that reminds me how much I hate the classroom, that closed-in box ruled by the strictures of the educational bureaucracy. Classrooms should be open, with plenty of windows for students and teachers to look out and daydream. And there should be no grades. Makers of standardized tests should be burned at the stake. I speak metaphorically of course. There is nothing less conducive to learning than tests. Press the right button and I get on my soap box.

DA: A special book project came to you in the aftermath of 9/11.

PM: García Lorca came to New York City to study English at Columbia University, but he was a terrible student and barely attended any classes. What he did instead was get to know the city and write some astonishing poems about the place. At a talk he gave in Havana subsequent to his New York visit he said, “I wrote ‘Poet in New York.’ I should have written, ‘New York in a Poet.’” He came to NYC in August 1929 and was in the city when the stock market crashed. New York was a very dark place then and he was able to capture that darkness and despair in his poems. The book that came out of that experience resembles a descent into hell.

In the aftermath of 9/11, which both Mark Statman and I witnessed directly, each of us individually was looking for some of the literature about New York we were familiar with that might speak to our sense of grief, displacement, and confusion. Both of us realized independently that Poet in New York was that book. It hadn’t been translated in 10 years and we concluded a new translation was needed in light of 9/11 and its aftermath.

DA: The book received high praise from John Ashbury who said your collaborative translation of Poet in New York was “The definitive version of Lorca’s masterpiece, in language that is as alive and molten today as was the original.”

PM: It was a labor of love and the love bore fruit. We agree with John Ashbery’s assessment, until a new translation comes along.

DA: And now you’ve found a home teaching at Emerson College.

PM: After a three-year stint in Las Vegas I accepted a job at Emerson College here in Boston. I like the place quite a bit. I have terrific colleagues and some very talented students. I teach fiction, poetry, and translation at both the graduate and undergraduate levels.

I am quite busy these days promoting Cubop City Blues. As a change of pace I am working on a collection of poems in Spanish. I think it’s some of the best poetry I’ve ever written. I hope to have a draft of the complete manuscript by December. I have a half-finished novel I need to get back to and a collection of essays. . .