Christopher Locke, who was born in Laconia, NH in 1968, is a poet, essayist, screenwriter and playwright. He is the author of the poetry collection End of Magic (Salmon Poetry, 2011). He has also published three chapbooks of poetry, Possessed (Main Street Rag, Editor’s Choice Award — 2005), Slipping Under Diamond Light (Clamp Down Press — 2002), and How To Burn (Adastra Press – 1995).

Locke has received several awards for his poetry, including a 2006 and 2007 Dorothy Sargent Memorial Poetry Prize, as well as grants from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and the New Hampshire Council on the Arts.

His poetry has appeared in such magazines and literary journals as Southwest Review, The Literary Review, Connecticut Review, The Chattahoochee Review, and The Sun, to name a few.

Locke currently resides in New Lebanon, NY with his wife and two daughters, and teaches literature and writing at The Darrow School.

Derek Alger: Starting at the beginning, were you aware of being creative from an early age?

Christopher Locke: Yeah, but in small ways. For one, I had to find creative ways to fill my time, as my memory of childhood includes a lot of silence. My dad was a disc jockey at a local AM station, as well as an occasional cashier at a corner store. And my mom worked at a shoe store for a family friend. If she was home, she slept a lot. So my brother and I needed to come up with interesting ways to kill time. This included sitting in the basement and reading through the stacks of history books my father had stored there; hiding out at the local library; and even writing my own stories. My third grade teacher read these painfully moral stories to the class (it was a Christian school), and I knew I could come up with something better. My first piece was about a skunk, two boys camping, and a lot of bodily functions. My teacher was outraged. It was then I knew I was on to something.

DA: You encountered a rather bizarre religious group as a kid.

CL: Pentecostal church. Totally fucked up. They didn’t talk about sneaking us into the Kool-Aid line with Jim Jones, but it was close enough. Weekly possessions, with bodies flailing about the church and so much horrible, horrible screaming. Or the preacher’s laying on of hands and filling true believers with ‘the spirit.’ They’d then collapse like a dish rag and be left to drool on the floor as the rest of the congregation sang songs of hope and enlightenment. So I believed, eight years old or whatever, that this is what everyone in America did on Sundays: go to church, watch your neighbors have demons cast out of their bodies, go home and have a nice family dinner. Totally normal. My poem “Possessed” (from the chapbook of the same name) highlights this time in my life.

DA: What were your high school years like?

CL: Dicey at best. We left the church-town of Laconia, NH and moved to Exeter, NH. My parents got divorced and I was pretty directionless. Then, in 10th grade, my friend Owen let me borrow a tape of this band called The Dead Kennedys and that was that; I absolutely fell in love with punk rock. 7Seconds, Circle Jerks, Suicidal Tendencies, Gang Green. Ahh, it was heaven. My friends thought I tried too hard to adopt the look, and they were probably right —- wearing shocking eyeliner to school, ripped jeans with the names of bands scrawled all over them, as if it proved I was part of something special and unique, something monumentally different from the dumb-ass jock culture that dominated our school. But it was this desire (desperation, really) to be different, to extricate myself from my own history, that I went to great lengths to rewrite myself: I lied all the time, even about stupid shit, (Do I play the drums? Sure I do! Live in a big house? Of course!!!) And this type of behavior, naturally, began to alienate me even further from my friends. I started doing drugs, whatever I could get my hands on. Even taking acid for the first time on a school night before dinner and then just hanging out with the family. Not one of my brightest decisions. Lessons came in bunches, but getting the answers took years. Thankfully, I had one teacher in high school, Ms. Smith, who saw something in me and encouraged me, particularly my writing. It was thrilling. I mean, here was an actual adult, and she spoke to me like…an equal! Or at the very least without contempt. I took her kindness and care with me into the world. It’s probably why I became a teacher myself. I’ve taught high school English for about 12 years. I really like teenagers, and relate to their sense of isolation and awkwardness. I think they get that I’m an authentic ally.

DA: Tell us about your college experience.

CL: I didn’t know a lot about college until my senior year in high school (my parents and grandparents didn’t go to university), but after I did learn, I became excited by the possibilities it offered. Finally, I thought: a way out! But I didn’t have a dime. After floundering for a year and a half post high school graduation, my mom and step father rescued me and paid for a semester at Keene State College in New Hampshire. That got the ball rolling. College was a time that my writing really began to change and improve. I knew I wanted to become a full-time poet; I know, I know: go ahead and cringe. But I was a kid! Anyway, I discovered writers like Gary Soto, Robert Hayden, Larkin, Lowell, Sexton, Keats and Blake, all The Beats. I read ‘Howl’ again and again until the room spun. Keene State’s main poet, Bill Doreski, became my mentor, though our relationship was contentious at best. He was gruff and unsympathetic, and I was determined to be a better writer than him. Sparks, as they say, flew a few times in class. But it’s all good, we now get along quite well and still keep in touch to this day.

DA: And after college.

CL: I moved to Portsmouth, NH and then Kittery, ME with my then girlfriend, now wife, Lisa Williams. I started the literary magazine Lungfish Review and even found a national distributor for it. Names in the poetry world started to send me their work. I couldn’t believe it. It was great fun. Myself, I wrote poetry every day like a fever. It was in Kittery I received my first acceptances into little magazines. Gary Metras, the wonderful publisher of Adastra Press in Easthampton, MA, offered to publish my first chapbook, “How to Burn.” I was 25 years old and absolutely living the dream. Menial jobs as a sandwich maker or photocopy jerk only added to the romantic charm: schlepp at bogus jobs during the day, write epic poetry and work on Lungfish Review at night. What could be greater?

DA: You then found a home teaching.

CL: Right. I was a waiter at a restaurant (Lisa and I had since moved to Northampton, MA so she could work on her Masters at UMass; I was finishing up my MFA at Goddard College), and a group of men came into the restaurant and were seated in my section. They were starting a school in Cummington, MA for troubled teens (as they called it) and were looking for an English teacher. Well, funny you should mention that, I said with a grin…

DA: You have clear ideas about writing poetry.

CL: I guess so, in that I want my poetry to be clear. Because though poetry is an art, it’s communication first. And something we all do is fail, so I write about that. I try not to fail better, as Beckett would endorse, but try and simply find a way out of permanent failure, small breathers that allow us to keep going, even when it feels like less than an option. This whole recent trend in modern poetry, kind of like a post-post take on L*A*N*G*U*A*G*E poetry (the poetry of nothing, I call it), is pretty absurd: feeling and direct intention are out, clever pairings of disparate ideas is in, the more nonsensical the better. I mean, in some ways I get it: many writers are still pissed off at Robert Lowell for making everything so touchy-feely, but this type of backlash strikes me as arrogant and reactive; soulless really. I’ll pass. Yet for many young writers, accessibility has become a four letter word, and Billy Collins is the ringleader! It’s weird. Accessible and simple are not mutually exclusive. I don’t need to read bizarrely paired lines that I don’t understand in order to feel like I’m part of some new avant garde. I mean, didn’t Ashbery cover that already with his first collection?

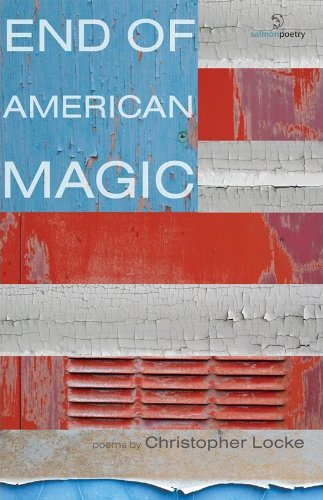

DA: Your recent collection, “End of American Magic,” received high praise from novelist James Frey, and your chapbook “Slipping Under Diamond Light” received accolades from Billy Collins, who said you write: “true-story poems about growing up in America” which are “delivered in plain, sure-footed language.”

CL: Yeah, they were kind. I appreciate the support. But it’s true. Image is key in my writing, but so is storyline. I wouldn’t necessarily call it Confessional, but I’ll allow that it’s narrative and story-driven. Some stuff I write about is from my own life, some not. I just sometimes make shit up. And that really bugs some people. A teacher at Goddard was irate a poem I wrote about molestation didn’t really happen to me. As if I didn’t have the right to make him feel something without me trying it on for size first. Novelists don’t get this type of flack. It’s strange.

DA: You’ve now found a home teaching at Darrow School.

CL: Yep, a tiny little boarding school in New Lebanon, NY. The campus is an old Shaker village, with the original buildings still intact. It’s quite beautiful, actually. I teach creative writing and literature, 10th and 12th graders mostly. Classes are small, so relationships can be authentic and valuable. That’s what I love most about teaching, the relationships I make with my students. That, and reading their work when they’re really excited about some topic or other. I relate to that.

DA: You’re also a playwright.

CL: Yes, this is something new in my life. Over the years, when I wrote fiction, I always noticed that I thrived most at dialogue —- it was my favorite part! So playwriting feels like a natural extension of this. I wrote my first one act, “Labor Day,” over the course of a few weeks during Christmas break 2009 at the behest of our Drama teacher at Darrow. I submitted it to a few places and it won a contest at F.A.C.T. Theatre of NYC, where it was given a professionally staged reading. It was fully produced with a company in Portsmouth, NH and there’s even talk of doing it with a couple of other theatres in the Midwest. It was also produced at Darrow, with the students in the main roles. Some faculty were, how should I put this, a bit worried by the final production. The play is about kids in their late teens/early 20’s doing what they do best: struggle, suffer, illuminate, and seek instant gratification. You know, swearing, drinking, etc.

DA: It’s amazing how true depictions of life in art tend to draw criticism from some in the so-called grown up world.

CL: Lenny Bruce said “Take away the right to say ‘fuck’ and you take away the right to say ‘fuck the government’.” But I get it. It was risky stuff, and there was concern that some depictions in the play messed with some of the kids’ issues. Fair enough. But still…(laughs). The kids were amazing in their roles, and proud of the work they accomplished. And I received so much support from the kids’ parents, as well as from many, many faculty too. It was really a great experience.

DA: You’ve written a second play.

CL: It’s called “The Pool”, and it’s receiving a staged reading in Northhampton, MA in August. Also, a pretty serious film production company, (RHI Productions), has it and wants to find a way to make it into a movie. Talk about your roller coaster ride…

DA: We should let everyone know you’re a happy family man.

CL: Indeed. Lisa and I have been married for over 15 years, and we have two daughters: Grace, 11, and Sophie, 7. They are the blood that beats my heart.

DA: Looking ahead, what’s on the agenda.

CL: World domination, obviously! (laughs) But seriously, I just completed a new collection of poems called “Waiting for Grace and Other Poems” and have it with a publisher, and a new play. A script, actually. It’s called “Can I Say” and is about a punk rock teenager growing up in a broken home in Exeter, NH. Autobiographical? Mmmmmaybe. (laughs)