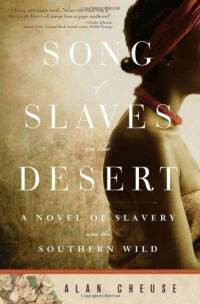

Alan Cheuse is the author of four novels, including his most recent, Song of Slaves in The Desert (Sourcebooks Landmark (March, 1, 2011), three collections of short stories, and the memoir, Fall Out Of Heaven (Atlantic Monthly Press. April 1989). His novel, To Catch The Lightening (Sourcebooks Landmark, October 1, 2009), was the winner of the Grub Street Prize for Fiction; his essay collection, Listening To The Page (Columbia University Press) was published in 2001; and he is the author of a collection of travel essays, A Trance Before Breakfast (Sourcebooks, Inc., June 1, 2009). He also was co-author with Nicholas Delbanco of Talking Horse: Bernard Malamud on Life and Art(Columbia University Press, April 15, 1997).

Cheuse is well-known as a book commentator, and a regular contributor to National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered.” His short fiction has appeared in numerous publications and literary journals, including The New Yorker, Ploughshares, The Antioch Review, Prairie Schooner, The Idaho Review, and The Southern Review.

The son of a Russian immigrant father and mother of Romanian descent, Cheuse currently teaches in the Writing Program at George Mason University and the Squaw Valley Community of Writers. He previously taught literature at Bennington College for close to a decade, as well as teaching at Sewanee: The University of the South, the University of Virginia, and the University of Michigan.

Derek Alger: Your most recent novel, Song Of Salves In The Desert, is a complex one dealing with an especially turbulent time in history.

Alan Cheuse: Slavery is America’s curse, as Faulkner called it. Biology is just a long line of people trudging through time. History is what they did as they trudged, both good and bad, and despite the “family values” document that those political ignoramuses Michelle Bachmann and Rick Santorum recently signed about the good in slavery that held black families together, there was nothing good in that so-called “peculiar institution”. Slavery wasn’t peculiar among the Greeks and the Romans, but when it became tied to racial theory, as it did in England in the 16th and 17th centuries, its radical cruelty became more apparent. But why should a writer from Jersey become interested in it in a deeply personal way?

I’d been a member, for about eight months, of a Jewish fraternity during my freshman college year at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania.. The president of the chapter was a charming and smart black student named Leonard Jeffries. I left Lafayette after freshman year, transferring to Rutgers and never thought about Jeffries, until the early 1990s when he surfaced in a controversy at the City College of New York. He had become head of the newly instituted Black Studies department, and seemed to enjoy stirring shit by announcing, among other things, that black people were “sun” people, full of light, vitality, energy, etc. and white people were “ice” people, with all that such a word entails. And he added that the Jews had bankrolled the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Oh, Lenny, I thought, you’ve changed since you were president of the Jewish fraternity at Lafayette! I filed Jeffries’ assertion away, and some years later doodled my way through the web, found some rants by black nationalists saying the same thing, and made a list of about four books by serious historians on the subject of Jews and slavery. What I discovered was that Jeffries had not a kernel of truth but perhaps a fly’s whisker of truth in his statement. Of the hundreds of Jews who lived in Charleston, South Carolina in the early and mid-19th Century, there were about four families that owned plantations with African slaves. (Charleston was the center of the slave trade in the US, the port to which, before the international slave trade was banned by various governments in the early 19th century, slave ships from Africa carried most of their prisoners, and even after the ban went into effect Charleston remained a busy center for slave trading among the U.S. states.)

DA: You said, “Once I’ve done all the research, the question is what to do with it,”

in reference to your novels on historical figures.

AC: All life, gossip, reading, eavesdropping, your troubles, family, your friends’

troubles and families, strangers with interesting stories, the news, travel, sights, insights, that’s the stuff of research for a novel or a short story. Graham Greene once put it this way. All a writer needs is a childhood. And I would add, an adulthood. But when you choose to work with historical material research becomes more codified. You can visit a location or a region where historical events that interest you took place. But how do you visit the time? You don’t. You have to face up to the fact that you have to invent the time based on all of your reading, insights, and what you might know about contemporary human character back from which you extrapolate in order to imagine characters from a certain time period in history. The one constant in writing anything is the interface between fact and imagination, and in a way historical fiction is as much an imaginative endeavor as so-called speculative fiction or what some of us still call science-fiction. One of its most skilled practitioners, William Gibson, said in a recent interview in The Paris Review, that all science-fiction is really about the present. You can’t say that about historical fiction. Otherwise you put your imprimatur on rank anachronism in both psychology and politics, among other elements in an historical novel. In any case, I want to emphasize the importance of the imagination in all of this, and by that I don’t mean that we invent what we don’t know any more than a scientist of any ethical standing would invent his or her findings. Forster says “only connect”. We try to connect, by means of our imagination, with times and events far-flung throughout the past. Writing fiction is difficult for me, no matter what the form or the material. Writing the Middle Passage sequence in Song of Slaves was the most difficult thing I ever had to do. I’m sure William Styron must have felt the same way when he wrote the concentration camp chapters in Sophie’s Choice, not to mention his Nat Turner novel.

DA: Do you think your father’s background gave you an early sense of history and a wider world beyond your early environment?

AC: Absolutely. It took me almost half a lifetime to realize—to admit to myself—how much I owed to him. But this is certainly one of things I learned from his life. About life’s uncertainty—one step one way, I wouldn’t be writing this—one step another way, and I’m here to say these things.

DA: You were born and raised in Perth Amboy, N.J. of a Russian immigrant father who was in the Navy Air Corps, and served in the Red Air Force against rebellious Muslims, China mail service.

AC: I had a lived or, what’s the cliché, a felt sense of history. I was part of it, as we all are, but as a child I didn’t know that. I thought it was only my childhood and my family and that was that. How they got to be who they were, how they all came to be living with each other in a small industrial town at the confluence of the Arthur Kill (the body of water that flows out of New York Bay to form the western boundary of Staten Island) and Raritan Bay, where the Raritan River flows out of the west Jersey hills to meet with the Atlantic Ocean). I did not understand, even though (fortunately) my father beat us over the head with his stories about his former life as an adventurous air cadet and pilot in the old Soviet Union and Japan and China before coming to the US, that I was the product of chance meetings within particular historical times and climes. You know, the American as apple pie scenario is a static myth, a myth that exists outside of time. Where do those apples come from? Who grew them? Who grew the wheat for the flour? Who sold it? Who baked the pies? That’s story, which happens in time. To live outside of time, in our contemporary days, is a kind of madness. Faulkner shows us that in the section on Quentin Compson’s suicide at Harvard in The Sound and the Fury. A sense of time=sanity. No sense of time=madness.

DA: You went to high school in an industrial town which was not exactly an encouraging learning environment.

AC: No. Part of childhood includes whatever sort of education you might have acquired, and in post WW-2 Perth Amboy, New Jersey, it was wretched. The teachers were all normal school graduates, and for the most part bored with their subjects. It was a bit like dining in an old Soviet restaurant. The waiters had their sinecures. Why should they have to be bothered to serve you? You felt as though you were starving to death in one of those restaurants. I got a much better education playing hooky with my friends, on trips to New York City (which, thank the gods, was fairly close by) and on the beaches and the water that surrounded our town on three sides.

DA: But you were interested in the written word at an early age.

AC: I have this memory—and I’ve written about it in a memoir I published before memoir was cool!—called Fall Out of Heaven –of my father sitting in a little alcove in what passed for the dining room of the apartment we lived in on lower State Street (which meant near the Bay) in Perth Amboy, and of a Sunday morning he typed and typed, trying, as he explained to me later, to write satirical stories in English in the style of the great Russian satirists Ilf and Petrov. He did not read much—we did not have any serious literature in the house, as I recall, and contemporary fiction only in the form of Readers Digest Condensed Books—but he was trying to write. Kind of a classic situation, much like any number of people you meet as a writer today. Kind of like trying to become a professional baseball player without practicing…Reading is for a writer the equivalent of practice. I remember reading, or listening to people read to me, from an early age. In sixth grade I entered a reading contest at the local public library with a little Greek kid named Spiro Giorgio—I’ll always remember him because he beat me by three books! To check books out for that contest I had to pass through the main entrance of the library, past a book rack where there was a copy of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. The title and the cover caught my curiosity, and every time I saw it I picked it up and tried to understand what was going on in its pages. Needless to say, that finally happened some years after sixth grade. Years later, when I was serving as a waiter at the Breadloaf Writers Conference I met Ralph, and I told him that story, and we had a good laugh.(I saw him quite a bit after that, at his apartment in NYC, and at Rutgers, when he was writer in residence and I was a teaching assistant in comparative literature)…

DA: Going to Rutgers University was a positive, life changing experience.

AC: Yes, it was. It opened my eyes on the world we never saw in Jersey, except for flashes of it that came with trips on the water and forays into Manhattan. I had world-class instructors, Francis Fergusson, who founded the drama division at Bennington College, where I later went to teach for nearly a decade (author of The Idea of a Theater, still the best book, I think, on drama), critics Paul Fussell and Richard Poirier, the poet John Ciardi (who was writing at the time for The Saturday Review of Literature), William Sloane, novelist and editor. The straight forward academics who taught there were swell, but these men were giants to me.

DA: And after graduation.

AC: Odd jobs, four months as toll taker of New Jersey Turnpike, where on the night shift I read Thomas Wolfe and Proust. Then I went to Europe for eight or nine months. Paris was, as the man wrote, a moveable feast, with the spirit of Hemingway hovering over the city for me, traveled to Spain and lived there for a while, in a cement house on the beach at Fuengirola, just south of Malaga. I had never seen tiled streets before, I had never seen a lot of things, I climbed with friends to the top of the low mountains at the coast, near Mijas, Picasso’s birthplace, and saw the coast of North African hovering on the horizon.. I took the ferry from Gibralter to Tangiers, and that was wonderful, as was the hashish in Tangiers.

DA: What came next?

AC: When I returned to the US, I took a job as a case worker at the old NYC Department of Welfare, and then at Fairchild Publications as an assistant editor. I covered the mink and seal skin auctions at the Hudson’s Bay Fur Trading Company at their offices in midtown Manhattan. And played a lot of chess at various coffee houses in Greenwich Village.

DA: Real world experience but a bit removed from the literary world.

AC: You can say that. After a year or so of this I got a call from John McCormick, one of my undergraduate professors at Rutgers, inviting me back to become one of the first members of the first class of a new graduate program in comparative literature, under Francis Fergusson. There were about half a dozen of us, including a young woman named Joan Acocella, who went on to become the New Yorker’s first rate dance critic and Jay Wright, the poet. I don’t know what was on their minds, but I know I was thinking, well, I like to read, and I’m now an adult—ha!ha!—so I figured I ought to get an adult profession. I stayed on at Rutgers a while, finished my course work, and then went on to teach while I was working on my dissertation (a critical biography of the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier).

Fergusson suggested I apply for a teaching post at Bennington College (in southwest Vermont). “You’ll like it there,” he said. “It’s not a real college…” And he was right. It was an extraordinary place, the top five percent of the students as good as any students anywhere in the world, and the half of the faculty that wasn’t intellectually fascist as good, too. The great colleagues I had there—Bernard Malamud, Nicholas Delbanco, John Gardner, Stephen Sandy, a French teacher named Georges Guy, Ben Belitt the poet and translator, poet Michael Dennis Browne—more than made up for the nut-cases and poseurs who staffed the rest of the literature division.

The freedom to teach meant we taught freely. In my case I devised a cycle of narratives from Gilgamesh to Hemingway, and taught myself—as I taught the students—most of what I needed to know to begin my own work. When I left, after nearly a decade (under circumstances too comical and painful and awful to recount here) I was ready to begin to write fiction. My wife at the time and I moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, where she took up a teaching post at the University of Tennessee. We made a pact. I would try for five years to write fiction and she would bring in most of the money. Within three years I had written a short story and sold it to the New Yorker, and I was off and running. I wrote and published a few more stories in little magazines. Then came a novel. By then the marriage had come to a shuddering halt.

DA: That was your novel about John Reed?

AC: Yes, that was when, like some kind of supernatural shape-shifter, I turned from nonfiction, vaguely scholarly writer—as in my dissertation on Carpentier, about whom I chose to write because I loved his work—into a fool of a fiction writer. It happened that I was trying to figure out what to do next, and I had the notion that I would write something like a biographical monograph, perhaps a hundred pages long, about John Reed, the American journalist and radical whose Ten Days That Shook the World was such an interesting piece of writing.

I began my research at the Rare Book collection at the Harvard Library, where the journalist Granville Hicks had convinced Reed’s widow Louise Bryant to send all of her late husband’s papers. I noticed that an historian named Robert Rosenstone (from Cal Tech)) had been going through the papers the year before. When I visited Hicks, then already quite elderly, in his upstate New York house, he told me that Rosenstone had recently been there to interview him about Reed. So since this talented young American historian was clearly at work on a biography of Reed I decided on the spot to write a novel about him instead.

Fools rush in…Maybe a good motto for all novelists? When I told my friend and then colleague novelist Nicholas Delbanco about my decision, he said, Oh, you’re lucky, you’ll have all of that material to work with whereas I have to make things up. So I thought I was lucky, until I had to wrestle with the task of what to leave out of the story!

DA: You also became friends with Bernard Malamud at Bennington?

AC: Actually, it was Malamud who introduced me to Granville Hicks. I had met Bern the summer before, at the Delbanco wedding reception. He was dressed in very (as I was to learn over the years) un-Malamud like fashion, with open shirt collar and love-beads around his neck. We talked. (We were going to be colleagues). He said, “I think we can be friends if you never show me anything you write…”

DA: You and Nicholas Delbanco co-edited Talking Horse, Bernard Malamud On Life And Work.

AC: Yes, after Bern’s death (in 1986) Nick Delbanco and I wanted to do something in tribute to him, and so we collected a bunch of his essays, interviews, lectures and notes, many of which had never been published before. Going through his papers at the Library of Congress was certainly an eye-opener for us, particularly about the meticulous way he went about revision. Every story, every novel manuscript—he wrote a draft in long hand, and then typed what he did, and made changes in the typescript, and then copied that over in long hand for a new draft, made changes, and then typed that…etc. For the stories, sometimes a dozen versions. And he’d correct and change galley proofs of the magazine versions, and then work on the galleys for a collection. He would work on tear sheets of magazine versions which he corrected for the book.

DA: Delbanco and you have also collaborated on a series Literature: Craft And Voice.

AC: Yes, which is currently going into a second edition, published by McGraw-Hill. The behind our book—on fiction, poetry, and drama—which we gained through long experience as teachers: when you improve students’ ability and interest in reading, you help them improve their writing. Many students, because of the proliferation of email, text messages, and now twitter, come to college unprepared to read long works in a sustained manner. That’s, as we see it, the equivalent of living for the moment, the view from Jimminy Cricket’s head. We think you can live both in the moment, and in the long view of time. But then novelists have to think this way. How else could they read, let alone write, long work?

DA: You also have written a novel, To Catch The Lightning: A Novel Of American Dreaming, about Edward S. Curtis, a photographer of the American West and Native American people.

AC: A long novel. I’d been fascinated with Curtis, and American Indians in a serious way—like all American kids I first became steeped in their lives in childhood as myth— And when I was about eighteen, and wandered past his photographs in the lobby of an art movie house in Cambridge, Mass., I knew I was seeing something important. Those images stayed with me for many decades. Who knows how a novel percolates up through the hard surface of the mind? This one came unbidden, after many years.

DA: You have also served as the regular book reviewer for the NPR radio program “All Things Considered” for many years.

AC: As of today, twenty-nine.

DA: You’ve literally literally have read thousands of books over the years, a remarkable feat of dedication.

AC: Once a week, on “All Things Considered,” I learned art of doing book review in two minutes, usually end up reading three books for everyone I decide to review.

DA: How do you find or decide which books to consider.

AC: My taste guides me, and that includes a sense of audience, and a certain duty to report on what seem to me to be the most interesting and entertaining books of the day. As it happens, my taste spans everything from experiment fiction to genre fiction, and good good books in the middle.

DA: You’ve found a home at George Mason University.

AC: A very formal place, after Bennington (and a few places, such as Michigan, University of the South, and University of Virginia, in between. But they encourage writers to write, and that’s a boon. From C.K.Williams to Carolyn Forche and Richard Bausch, to name a few, some fine writers have taught at Mason. Right now I have some wonderful colleagues in Susan Shreve, Steve Goodwin, Helon Habila, Courtney Brkic, Eric Pankey.

DA: What type of courses do you teach?

AC: Fiction workshops, and some literature. American modernism, always great to do because you get to reread Faulkner and Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. And I do a cycle of courses in the short story, from Europe to America to world story. A lot of great reading.

DA: What are you working on now?

AC: I don’t want to jinx it, but I can say that after years of wrestling with long books, the Curtis novel, and then Song of Slaves in the Desert, I am trying to work short. A short novel. I like the short form. Over the years I have published, I guess it is, about half a dozen novellas, the latest one being in the current—2011—issue of The Idaho Review. So I like short. But the novels tended to get long. You have to be more a long-distance runner rather than a sprinter for many reasons in this thing we do. When you’re running long distance, people sprint past you, but they fall by the wayside. You just keep running at your own pace.