Between July 11th and August 29th, the Seattle Art Museum’s exhibition Everything Under the Sun: Photographs by Imogen Cunningham will showcase the work of a Northwest native whose diverse photographic oeuvre celebrates the unification of realism with imagination. On display at the SAM Third Floor Galleries will be sixty of Cunningham’s photographs, drawn from the museum’s permanent collection, highlighting some of this modernist’s most notable landscapes, botanicals, and portraits. The photographs in the exhibition will span sixty years of the artist’s remarkably prolific career (Cunningham shot her first self-portrait in 1906 and continued to take pictures until her death at age 93). Even a small sample of her work reveals how Cunningham used an adamantly realist aesthetic as a provocative gateway to subjective interpretation.

Cunningham’s artistic project was grounded in the view that photography, unlike other art forms, should aim simply to represent objects in their unadulterated states. Her colleague Edward Weston, with whom she co-founded the objectivist Group f/64 (along with five other photographers including Ansel Adams) applauded Cunningham’s visual integrity when he wrote: “She uses her medium, photography, with honesty, no tricks, no evasion: a clean cut presentation of the thing itself, the life of whatever is seen through her lens, life within the obvious external form.” Cunningham graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in Chemistry, and her scientific inclinations certainly manifest themselves in her art. I was struck by the surprising clarity of her shots–she experimented with various chemicals and techniques to achieve unprecedented definition–and the botanist’s accuracy with which she captures the structural details of the flowers in her garden.

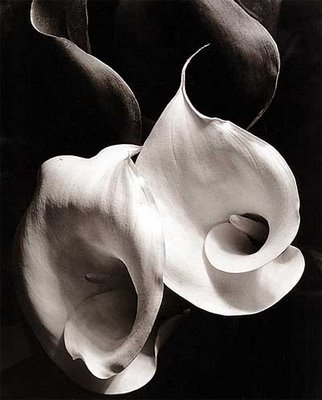

In their naturalist manifesto, the artists of Group f/64 rebelled against the soft-focus, painting-inspired Pictorialist tradition that had long dominated the field. Yet although Cunningham forgoes the dreamy embellishments that were still popular into the 1920’s and 30’s, even her botanical photographs evoke a stirring, if inarticulate, sense of dramatic interiority. Take, for instance, “Two Callas” (1929), a close-up of two white lilies against a gorgeously inky black background. “Two Callas” seamlessly pairs straightforward visual honesty with deep imaginative potential. While one flower captures full light and faces the viewer, luminously white, its shadowed partner looks slightly downward and away from the camera. The latter lily’s shading accentuates the grainy details and irregularities that go unseen in the former, and renders the two pistils two totally distinct colors. Subtle variations in light and angle endow these identical flowers with intensely different emotional auras. Their contrast makes it impossible not to personify the lilies, or at least to reflect on their symbolic implications for aging, fertility, relationships, or whatever other tensions may be at the forefront of the viewer’s mind.

Everything Under the Sun will also feature “The Unmade Bed” (1957), one of Cunningham’s most iconic photographs and an epitome of her art’s simultaneous sparseness and depth. In content, “The Unmade Bed” is nothing more than its title suggests. Yet through the linens’ fascinating combinations of light and texture, Cunningham draws the viewer into an inviting, sensual space that radiates the heat of a bed that has just been abandoned. The presence of a few hair pins in the foreground, too, lends the image a surprisingly intriguing narrative quality. However commonplace, these small objects disrupt the softness of the rest of the bed, urging the viewer to piece together the human story behind this vacated space. For me, this photograph has alternately suggested longing, satisfaction, playfulness, and anxiety. Without any elaborate manipulation, Cunningham transforms an everyday scene into an exercise in projection and fantasy.

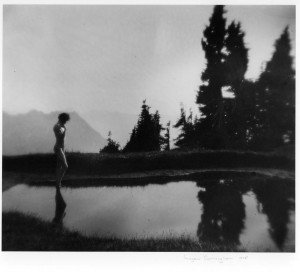

Also not to be missed are photographs from Cunningham’s early series “On Mt. Rainier” (1915). Purportedly the first sequence of male nudes to be circulated within the fine art community, “On Mt. Rainier” drew harsh public criticism for its unabashed representation of the male body. But while she never regretted the decision to disrobe the model (her husband, Roi), in her old age Cunningham did affectionately depreciate these among other early photographs for their romantic quality: “They are from what I call my ‘dream period,’ when I … thought I understood poetry.” Though they mimic the pictorial art that Cunningham would later deconstruct, the photographs in “On Mt. Rainier” are stunning in their beautiful composition and vivid tones. They are also particularly touching given the relationship between the newlywed artist and model.

Making your way through Everything Under the Sun, you’ll sense a powerful integration of clarity and haziness, frankness and romance, universality and individuality. Working within a medium and movement grounded in scientific accuracy, Imogen Cunningham proved that realism can function as a vehicle for imaginative flexibility.