Inspiring muralist, writer, and printmaker, Dave Loewenstein strives for a “people’s art.” His community murals incorporate many voices and can be seen throughout the United States, in Northern Ireland and even South Korea. His prints challenge social and political issues, are exhibited nationally, and can be found in permanent collections of the New York Public Library and the Center for the Study of Political Graphics in Los Angeles. He is the co-author of Kansas Murals: A Traveler’s Guide, a 2007 Kansas Notable Book Award Winner, published by the University Press of Kansas; and the co-director of the documentary film Creating Counterparts which won Best Documentary at the 2003 Kansas Filmmakers Jubilee. He hopes to someday write a book of essays inspired by his travels as a muralist (and we do, too!). His work is widely recognized and has impacted many individuals and communities.

Growing up just north of Chicago, Loewenstein had big dreams of being the next great Chicago Cubs’ pitcher. Despite incredible shyness, he was attracted to situations with a large public audience, and shared his passion for baseball with a natural inclination to the arts. For a while unsure of his path, a surprising ‘aha’ moment convinced him to embrace the visual realm as a full-time ‘vocation and lifestyle.’

Growing up just north of Chicago, Loewenstein had big dreams of being the next great Chicago Cubs’ pitcher. Despite incredible shyness, he was attracted to situations with a large public audience, and shared his passion for baseball with a natural inclination to the arts. For a while unsure of his path, a surprising ‘aha’ moment convinced him to embrace the visual realm as a full-time ‘vocation and lifestyle.’

Currently residing in Lawrence, KS, Dave’s vocation requires him to travel extensively in order to create the colorful, multidimensional, murals that have become his trademark. Community-inclusive, Dave works tirelessly to translate oral histories into visual stories that carry the viewer and community-at-large from past to present, and into the future. These murals serve to transform the walls they re-purpose, the people they involve, and the communities they inspire.

Recently completing his sixth and final mural in the Mid-America Arts Alliance (MAAA) Mural Project, which includes all MAAA States (KS, OK, MO, AK, TX, NB), Dave had some down time to answer many of my festering questions. I was fortunate enough to work under Dave’s direction on one of his community design teams and experienced first-hand the effects inspired through his work.

Read on to learn more about Dave, his mural projects, his prints, other projects, and what’s in store for his future.

Emily Frankoski: Where are you from originally and where do you now reside? How did you get “from here-to-there?

Dave Loewenstein: I grew up in Evanston, Illinois just north of Chicago. I came to Lawrence for graduate school in 1991 after being an apprentice on an organic farm in upstate New York after going to grad school at Purdue University in Indiana after going to undergrad at Grinnell College in Iowa. I’ve been based in Lawrence ever since.

EF: What did you want to be when you grew up? Compare child-Dave with adult-Dave. Are there more similarities than differences, or?

DL: Until the age of 15 or 16 I wanted to be a professional baseball player – a pitcher for the Chicago Cubs. I’ve always been a self-starter. I practiced pitching by throwing a rubber ball against a wall of my elementary school. I practiced painting by going out into the farmlands outside Grinnell, Iowa (where I went to college) to make landscapes. Both were a way for me to be out in public with a purpose. That was important because I was painfully shy and uneasy in most public situations. It’s not the Major Leagues, but making murals and doing street art have similar aspects to being on the pitcher’s mound. You’re in public. There’s a big audience. You’re working with a team but have to make tough decisions on your own, like whether to throw a fastball or curve…

EF: How did your relationship with art begin? What is your background in art?

EF: How did your relationship with art begin? What is your background in art?

DL: My relationship with art began like everyone else’s. I drew, I sang, I danced. I was an artist until some adult said – maybe someday I could be an artist when I grew up. That slowed me down for a while. I didn’t really make much after that until my second semester at Grinnell when I took a beginning drawing class with Robert (now Bobbie) McKibbin. His passion and great teaching were the impetus for me to begin again. He made landscapes of alleyways and backyards, very unpicturesque places that he made beautiful and monumental. That felt right to me and so following his example, I tried too.

My background? I grew up in Evanston. My mom stayed home and took care of my brother and I. My dad worked as a set-designer for PBS. I went to public schools and spent most of my free time, when I wasn’t playing baseball, wandering around by myself observing and imagining.

EF: What led you towards art as a career?

DL: Career? I’d call it more of a vocation and lifestyle. I suppose like most other grad students I thought I would graduate, get a sweet teaching position, find a gallery to represent my work and chill. But instead I got more and more involved with social and political actions, started making stencils and began to question the purpose and function of the landscapes I was making. This led to a minor crisis where I left grad school, disregarding the advice of the head of the art department who told me I was “making the worst decision of my life.”

EF: How would you describe your artwork in 4 words or less?

DL: Populist.

EF: If you weren’t an artist, what would you be and why?

DL: A public school teacher. It is vitally important work.

COMMUNITY-BASED MURALS

EF: Explain the beginning of your relationship with mural-making. What attracted you to this type of work?

DL: Here is an inspiration and a grand moment of déjà vu. In 1990, just before I moved to Lawrence I traveled to central Mexico and saw for the first time a Diego Rivera mural, a Jose Clemente Orozco mural and a David Siquerios mural among many others. They blew my mind. I was awestruck, inspired and intimidated. I instantly felt a cold sweat overtake me. Seeing these murals, although at the time I never would have imagined becoming a muralist, was a direct challenge to the kind of art I had been making. Where I had been focused on small personal landscapes for an audience of gallery and museum goers, the Mexican muralists made giant cultural histories in public that critiqued and satirized the establishment. Big difference, and I knew which one I was more attracted to and it wasn’t what I was doing.

DL: Here is an inspiration and a grand moment of déjà vu. In 1990, just before I moved to Lawrence I traveled to central Mexico and saw for the first time a Diego Rivera mural, a Jose Clemente Orozco mural and a David Siquerios mural among many others. They blew my mind. I was awestruck, inspired and intimidated. I instantly felt a cold sweat overtake me. Seeing these murals, although at the time I never would have imagined becoming a muralist, was a direct challenge to the kind of art I had been making. Where I had been focused on small personal landscapes for an audience of gallery and museum goers, the Mexican muralists made giant cultural histories in public that critiqued and satirized the establishment. Big difference, and I knew which one I was more attracted to and it wasn’t what I was doing.

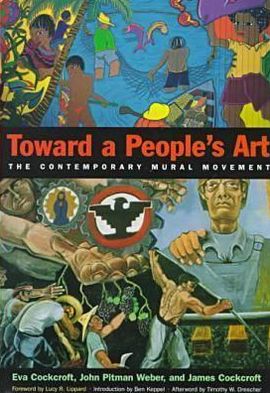

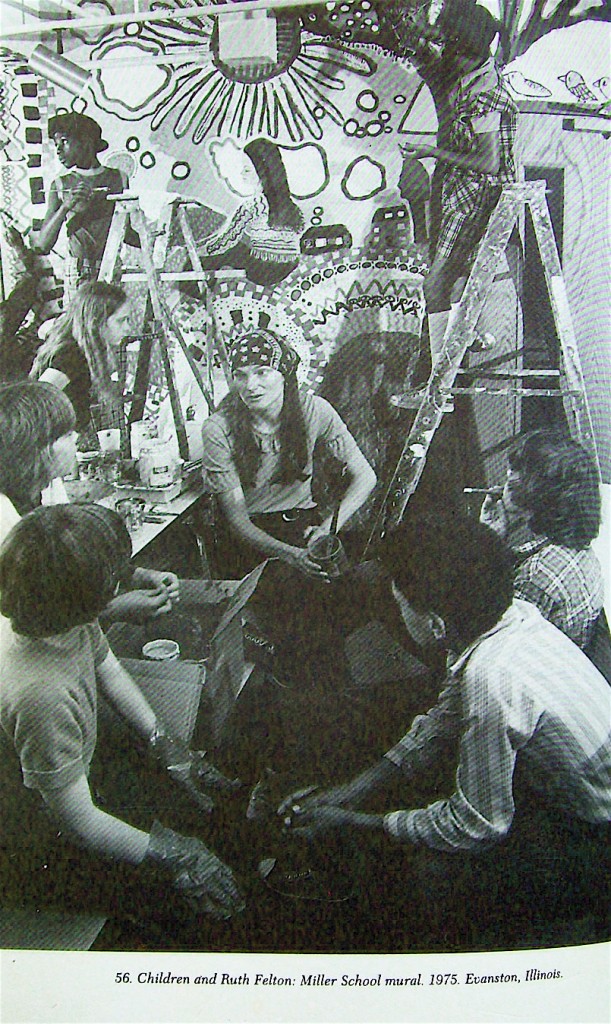

A few years later as I was trying to find my way as an artist after leaving grad school, I went to the art library at the University of Kansas searching for inspiration. I ended up looking through books about public art and came across one title “Toward a People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement.” I’d never heard of the book or the ‘Movement.’ I thumbed through the pages looking at photos of groups of people working on community murals. I liked it. Then I came to page 140 – a black and white photo of some kids sitting around an artist while others work on a mural in the background. Déjà vu, big time.  It was only when I read the caption below the photo that I realized why. It read, “Children with Ruth Felton, Miller School mural, Evanston, Illinois, 1975.” I was nine in 1975. I grew up in Evanston. I went to Miller School and after closer inspection realized… I was in the photograph. I was in a photograph in the book I was hoping would inspire me – whoa. I took it as a sign and haven’t looked back.

It was only when I read the caption below the photo that I realized why. It read, “Children with Ruth Felton, Miller School mural, Evanston, Illinois, 1975.” I was nine in 1975. I grew up in Evanston. I went to Miller School and after closer inspection realized… I was in the photograph. I was in a photograph in the book I was hoping would inspire me – whoa. I took it as a sign and haven’t looked back.

EF: Explain your involvement with the Mid-America Arts Alliance (MAAA) and the Community Mural Project?

DL: The Mid-America Mural Project developed out of conversations I had with MAAA CEO Mary Kennedy about the potential impact of community-based public art in areas with limited access to funding and trained artists in the field. Initially the project was organized as a pilot program for two states, Oklahoma and Kansas with funding from the Stimulus program. The Tonkawa, Oklahoma and Newton, Kansas projects were a great success, so much so that the program was expanded first to Joplin, Missouri then Arkadelphia, Arkansas and eventually to all of MAAA’s states. This year we completed the last two murals in the six-state region starting in the spring in Waco, Texas and this October we finished in Hastings, Nebraska.

EF: Roughly, how long did it take to create each mural? How long did the mural project last?

DL: Our projects are usually 2-3 months. 2010 – 2013

EF: How many murals were completed within this project and where are they located?

DL: 6 murals

[acx_slideshow name=”Dave Loewenstein Murals” height=”200px” width=”600px”]

– Tonkawa, Oklahoma (2010) Listening Back, Dreaming Forward: The Rhythms of Tonkawa

– Newton, Kansas (2010) The Imagineers

– Joplin, Missouri (2011) The Butterfly Effect: Dreams Take Flight

– Arkadelphia, Arkansas (2012) From A Dream, to the Promise

– Waco, Texas (2013) Storytellers: Sharing the Legacy

– Hastings, Nebraska (2013) Working Together for a People’s Art

EF: Briefly describe your community-inclusive process from conception to execution (development, research, community input, inspiration, community paint days, etc).

DL: I like to see the murals we make as visual poems that can become places of memory and pride. They can also be catalysts for jump-starting community action. As residents shape an image of themselves, their memories, challenges and hopes for the future, they often rediscover how collectively they have agency in the life of their community.

Murals are a technology for storytelling that is accessible to participants of differing abilities, that bridge barriers of language, do not require elaborate tools, and can be adapted to almost any setting. As a form of public performance, murals also provide new opportunities for strangers to meet and talk about the work being done, its relevance, and its meaning as art and as a form of social action. This has been my experience working with communities for the last twenty years, to focus on an art that reaches people outside of established art institutions which reflects their histories, concerns, and visions for the future, and to build these works in a form that is as visually strong as its narrative is rich with local meaning.

Murals are a technology for storytelling that is accessible to participants of differing abilities, that bridge barriers of language, do not require elaborate tools, and can be adapted to almost any setting. As a form of public performance, murals also provide new opportunities for strangers to meet and talk about the work being done, its relevance, and its meaning as art and as a form of social action. This has been my experience working with communities for the last twenty years, to focus on an art that reaches people outside of established art institutions which reflects their histories, concerns, and visions for the future, and to build these works in a form that is as visually strong as its narrative is rich with local meaning.

My process, which continues to be honed with each project, begins with community meetings. After all, in most cases I’m a visitor who will rely on the experiences of local people to shape a meaningful artwork. Larger meetings lead to design workshops where a smaller group of volunteers begin the big brainstorm – exploring potential themes and media while considering the intent of the project and how audiences will be drawn into a dialogue with what is made. We meet regularly to gather and create the raw material, in the form of photos, drawings, stories, objects and interviews, needed to fashion a work of beauty and significance. From there, I along with an assistant and apprentice lead a small mural team in translating and shaping this research material into a design – like a visual poem, fable, or allegory, that embodies the heart of the story we are trying to tell.

After the design has been approved, we move outside projecting the image at night (while simultaneously doing improv shadow theater) and then painting, initially alongside community members who are invited to paint during a Community Painting Weekend. The projects conclude with elaborate dedication ceremonies often accompanied by local music, home made treats and lots of fine speeches.

After the design has been approved, we move outside projecting the image at night (while simultaneously doing improv shadow theater) and then painting, initially alongside community members who are invited to paint during a Community Painting Weekend. The projects conclude with elaborate dedication ceremonies often accompanied by local music, home made treats and lots of fine speeches.

EF: It must be challenging condensing the expectations of community members into one cohesive mural. What difficulties have you encountered during the process of creating these murals?

DL: Yes, it is importantly challenging. Those difficulties, arguments, disagreements and misunderstandings are central to the purpose of these projects. At their heart, these projects are about reengaging citizens with the potential of the public realm as a venue for their histories hopes and dreams. Our hope is this process – openly discussing what and who is important in the mural, coming to consensus and then painting together – can be a model for future dialogue about other important issues and then finding ways to act on them.

I think the toughest things we’ve encountered don’t come from disagreements within our design teams, but from outsiders who want to control the content without participating. Not surprisingly, the issues that divide us politically, socially, and economically are the ones that attract the loudest voices. But this isn’t a negative. It is vitally important for all of us to consider how we are being represented (in politics, the media, at work, etc.) and how we can act to change those representations to more accurately reflect our histories, communities and cultures.

EF: What has been the feedback from these murals? Both positive and negative.

DL: I’ll refer you to a couple articles written about the project for this question:

– Here’s an article about the final mural in the MAAA project in Hastings, Nebraska.

EF: What has been your most memorable moment (or moments) during this Community Mural Project journey? What has given you the most satisfaction?

DL: The people I’ve met and friends I’ve made. This project has woven together a new network of relationships in my life that I never could have imagined. I am grateful. These projects also force me out of the bubble I live in at home. Working on these murals, I have learned so much more than I ever learned in school about the history and current affairs of the U.S. I’m a big fan of Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States.” Traveling to places like Arkadelphia or Waco and having to really understand what’s going on from the ground up feels akin to Zinn’s approach to history, which starts with the stories of regular people and often the ones we don’t read about in mainstream history books.

EF: In your opinion, what is the point of public art? Is it essential or a “frill”? What can it do for a community?

DL: At least as essential as golf courses and billboards.

Public art especially when it’s rooted in community can combat the cold and calculated designs of capitalism. It can help to shape and assert a community’s identity. Public art also has the potential to create places of memory where People’s history (see Howard Zinn’s book “A People’s History of the United States,” and a book I contributed to, “Celebrate People’s History.”) is shared and remembered.

Community-based public art returns to local people the tools to represent themselves as they see fit, the space to be heard, and the opportunity to dream in public.

STENCILS, PRINTS, & PICTURE STORIES

EF: What is your source of inspiration for making stencils?

DL: The prints I make, most of which are spraypaint stencils, are focused on current social and political issues. Many are used by organizations and individuals involved in the movements they support. Most are seen first on the street as wheatpastes or protest signs. Later they are exhibited in shows and circulate via the internet and other media.

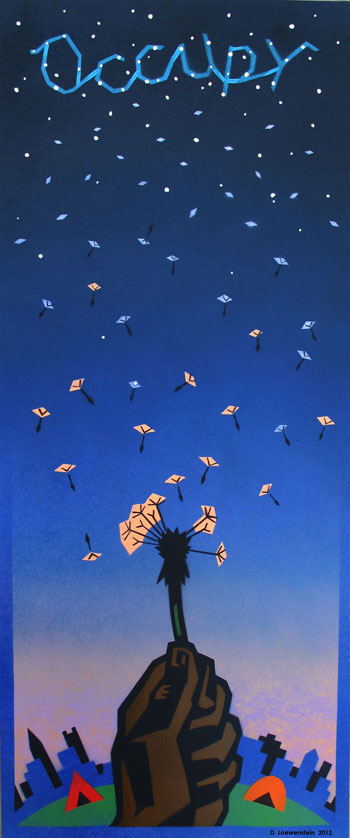

EF: Describe your involvement with the Occupy movement?

DL: Soon after the occupation of Zuccotti Park I joined forces with an international alliance of printmakers who formed the group Occuprint. We made posters and graphics that articulated the spirit of the movement and supported its ideals. Although Occupy has subsided in the mainstream press, Occuprint continues, last year supporting relief efforts in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Ironically perhaps, a portfolio of these radical prints were recently acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York including my stencil “Tip of the Iceberg.”

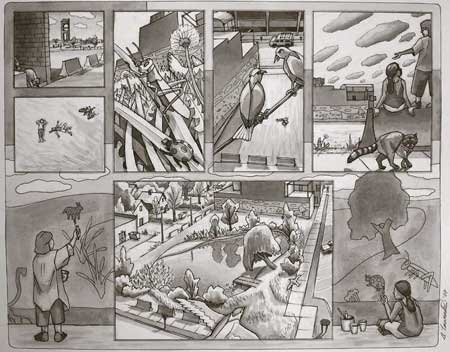

The picture stories are short wordless narratives inspired by my waking dreams walking around East Lawrence.

EF: Where do you exhibit your works?

DL: Mostly in exhibitions of political and social justice printmaking, recently in San Francisco in “Rainbow Warriors: The Art of Resistance,” in Bolzano, Italy for “We Are the 99%,” and “Graphic Advocacy: International Posters for the Digital Age” which is touring the U.S. I’ll also be having a show with my partner Ashley Laird beginning in January in Kansas City.

GIVE TAKE GIVE

EF: Tell us about your project, Give Take Give.

DL: The Give Take Give project, supported by a Rocket Grant through the Andy Warhol Foundation, explores and documents the gift economy and stories that have developed in and around a trash dumpster near my apartment. I’d been taking photos of the dumpster for years and always thought I would make something of them but hesitated until last year. That’s when developers plans for a new hotel to be built in the field right across from the dumpster were approved by the city. The chances were good that the dumpster would be no more once construction began (I was right), so I went to work.

My thought was that by shedding light on this alternate economy, hidden in plain sight, others might be inspired to reflect on how gifts of labor, teaching and time, as well as things, can help bind us together in a connected circuit of good will. In other words, how this asymmetrical cycle of giving and taking engenders new relationships, creating a network of mutual indebtedness.

The Give Take Give book which includes photos and stories from the last few years was released in conjunction with an exhibition and an evening of storytelling at the Lawrence Percolator last May. There’s lots more in the book and on the accompanying blog: givetakegive.blogspot.com

FUTURE PROJECTS

EF: What does the future hold for D-Lo?

DL: Hopefully, a little rest. I’ve been on the road for the last seven months – Milwaukee, Wisconsin to Songdo, South Korea to Waco, Texas to Sioux Falls, South Dakota to Hastings, Nebraska.

After that…

I’ll be getting ready for a show with my partner Ashley Laird at the BNIM Architecture offices in the classic Power and Light building in Kansas City. It opens January 17th.

I’ll be working on a new mural next summer in conjunction with the Ad Astra Festival in Independence, Kansas.

I‘ll also be writing more, especially for a (someday who knows when to be published) book of essays about my travels as an itinerant muralist.

And I’m sure I’ll be making more prints. The best way to keep up to date with me is to check my blog: loewensteinmuraljournal.blogspot.com

THIS-AND-THAT

EF: When you are not creating, what might one find you doing (are you still teaching)?

DL: Tending the vegetable garden, practicing my baritone ukulele and just being with my partner Ashley and our dog Mojo.

EF: For whom do you create? Who is your audience?

DL: This is a great question and one that I think about a lot. As a muralist I am aware of the many different audiences that will see our projects. Clearly it’s not just museum and gallery goers. These murals are located in neighborhoods and on Main Streets that folks from all walks of life frequent. We talk about this in our design team meetings as we craft images and stories that will engage and speak to a broad cross section of the community.

Also with my prints for Occupy and other social justice issues, I think carefully about whether they are made to inform, challenge, support, satirize and/or question. The answers influence how the images and text are designed. And then there are the things I make just because I want/need to. Some are shared on the streets, others like the picture stories are shared in exhibitions, on-line and in print.

EF: To date, which project has given you most satisfaction?

DL: That’s tough. I think it’s usually the one I’m working on. Today it would be the Pollinators mural painted in 2007 in Lawrence because it’s being threatened by a developer’s plan to tear it down and build upscale apartments in its place.

EF: What artists do you admire and why?

DL: I’ll name three contemporary ones. There are many more. Kara Walker who is best known for cut paper tableaus that reimagine the Antebellum South. John Pitman Weber a leader and visionary of the contemporary mural movement, whose Chicago murals were an early inspiration for me. Blu, the Italian street artist whose stop motion mural films are remarkable.

EF: What is your favorite book?

DL: The one that has stayed with me the longest is “The Little Prince” by Antoine de Saint-Exupery My grandmother gave me a copy on the day I was born.

EF: What are you currently reading?

DL: “The Faraway Nearby” by Rebecca Solnit

EF: Do you have a favorite quote?

DL: Many. Here is one from the Gwendolyn Brooks poem “Paul Robeson.” “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.”

EF: Where can we see more?

DL: Come visit my studio in Lawrence, Kansas, check out the actual murals across the U.S. and keep up with my blog for news of upcoming exhibitions and events.

Website: http://www.davidloewenstein.com/

Blog: http://loewensteinmuraljournal.blogspot.com/

Give-Take-Give: http://givetakegive.blogspot.com/

The Mid-America Arts Alliance (Community Mural Project): http://midamericamuralproject.blogspot.com/