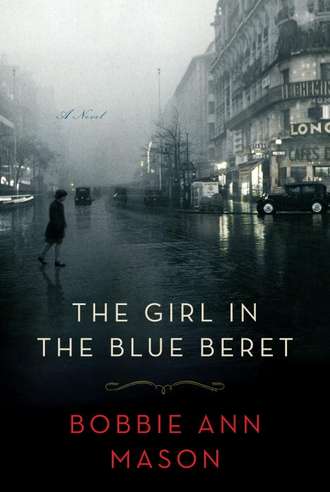

Bobbie Ann Mason’s most recent novel, Girl in the Blue Beret (Random House, June 28, 2011) is scheduled for release in paperback by Random House Trade Paperbacks on July 10, 2012.

Mason’s first short stories were published in The New Yorker, and subsequently included in her first book of fiction, Shiloh & Other Stories (1982), which won the PEN/Hemingway Award. The story collection was also nominated for the American Book Award, the PEN/Faulkner Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

In 1985, Mason completed her first novel, In Country, which was made into a feature film starring Bruce Willis and Emily Lloyd. Her second novel, Spence + Lila, was published in 1988, followed by two other novels, Feather Crowns (1993) and An Atomic Romance (2005).

Mason, who was raised on her family’s dairy farm in western Kentucky. has published several short story collections, as well as Clear Springs: A Memoir, a family history which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Her short stories have appeared in numerous magazines and literary journals, such as The Atlantic Monthly, Mother Jones, and The Paris Review, to name a few.

Mason earned a bachelor’s degree in English at the University of Kentucky in 1962, and then completed a master’s degree at the State University of Binghamton in 1966. She completed her Ph.D at the University of Connecticut in 1972, where she wrote her dissertation on Vladimir Nabokov’s Ada, and her work was published in both hardcover and paperback as Nabokov’s Garden. A former writer-in-residence at the University of Kentucky, Mason is a member of the Authors Guild, PEN, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers.

Derek Alger: How did the idea for The Girl in the Blue Beret come about?

Bobbie Ann Mason: While taking a French class, catching up on college French, I started thinking about my father-in-law’s time in World War II, when his B-17 was shot down on the border between Belgium and France. He made his way through France to safety with the help of the French Resistance. I started wondering what it would have been like for him in that dangerous situation, not knowing the language. I reread his memoir, and he mentioned a girl who had guided him from the train, a girl in a blue beret. Voila! My title.

DA: And then the real work began.

BAM: Yes. I wondered what the story would be. Right away I imagined an ex-flier, years later, going back to find the people who had helped him during the war. I wanted to know what it would be like to go on his journey, searching for illumination of the past. I felt in a way that I was on the trail of the girl in the blue beret.

DA: Your travels helped fill in that context.

BAM: Yes. I went to France several times. I looked up some members of the Resistance who had helped my father-in-law. They could not have been more welcoming or appreciative of the Allied forces that had helped liberate their country. They were still so grateful, and their memories were very much alive. They were generous to me and helpful with my efforts to put myself back in time. Writing about that period was daunting, but those people gave me confidence. They wanted their stories to be told, their sacrifices to be remembered. It was really a very profound experience for me to have some of them share their memories and to trust me to get at the emotional truth of that time. It was a challenge, and no book I’ve written has ever involved me so deeply.

DA: In Paris, you met a woman who had served as guide in Resistance.

BAM: She was my father-in-law’s guide, and she was my model for the girl in the story. She showed me her scrapbooks of mementoes from the war — the ration coupons, newspaper notices, photos and so on. She showed me a photo of a young man who was also a courier she had worked with in the war. He was my inspiration for Robert, the shadowy figure in the novel.

DA: You’re the oldest of four raised on a Kentucky dairy farm.

BAM: It was an isolated corner of Kentucky, far from any city. My parents encouraged me to read, but there were few books available, certainly nothing called literature. I started with the Bobbsey Twins and Nancy Drew. Then I discovered Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, a book I cherish to this day. It enthralled me. Louisa May Alcott was a real WRITER. Her character Jo March was a writer. My reading in high school was scanty, and I didn’t like the force-fed books in English class. We didn’t have essay writing. Or art or music, for that matter. Or languages, except for Latin, which I loved. I didn’t find any more books I liked until freshman English in college, when we read Salinger and Hemingway and Thomas Wolfe.

But my real sources, the influences that were of value to me later as a writer, were the natural world — the infinite sensory details of growing up on a farm — and the language of country people. No amount of reading could have given me those treasures.

DA: And then off to college.

BAM: I majored in English, with a minor in journalism, at the University of Kentucky. Writing columns for the school newspaper and short stories for a creative writing class deepened my ambition to be a writer. And I was excited about twentieth-century art history and French literature.

DA: After college you continued north.

BAM: At the time there were very few writing programs. I applied to three or four and didn’t get in, so I went to New York and tried to use my journalism background to get a job. For a little over a year I worked for a fan-magazine publisher. I wrote for TV Star Parade and Movie Stars. These weren’t the scandal rags of today. They were fluff, but I rather enjoyed writing about Annette Funicello and Fabian and the Bonanza guys. But I was ready to get back to school and read books, so I was lucky to get into the Ph.D. program at Harpur College, now SUNY Binghamton. I finished at the University of Connecticut, and by then I felt it was really time to write fiction. Since I never got a job with my Ph.D, I was free to sit down with fiction, at last.

DA: Would you describe yourself as writing or reading more in grad school.

BAM: I didn’t read anything then except books for course work. There was no time. Graduate study was difficult enough for me, but I spent most of my time preparing for the classes I taught as a teaching assistant. I was in over my head.

DA: Do you remember your mindset at the time.

BAM: Yes. I was shy, frightened and deeply desirous of a niche where I could read and write and not have to speak. In college I had discovered Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Salinger, and in grad school I latched onto Joyce and Nabokov. I took an independent study in creative writing with Robert Kroetsch, a renowned Canadian writer, but I didn’t get any encouragement there.

DA: What interested you about Nabokov.

BAM: The sensibility. His way of looking at sunlight and bugs. The puzzle-solving. The details. I wasn’t thinking about academia. I was thinking of the intricate nature imagery in Nabokov’s Ada. It was breathtaking. I was thoroughly absorbed in it.

DA: Your dissertation on Ada was published in both paperback and hardcover as Nabokov’s Garden.

BAM: What a surprise. It didn’t get me a job, though. It turned out I didn’t have the kind of mind prized by academia.

DA: You do have experience as a teacher.

BAM: I never got a teaching job with my Ph.D in literature, but I taught journalism part-time for about six years at Mansfield State College (now university) in Pennsylvania. After I began publishing fiction in the 1980s, I did the odd workshop here or there, but never had a teaching position. I was writer in residence at the University of Kentucky for ten years, but I didn’t teach courses.

DA: What was your apprenticeship as a developing writer like?

BAM: It took a long time to discover my material, and to develop the maturity to know how to approach it. I wrote a couple of novels during the seventies, just getting focused on fiction, trying it out.

DA: Your first published story was in the New Yorker.

BAM: That was the twentieth story I submitted. It always kills me that young writers will despair after receiving two rejections from the New Yorker. That period for me was very exciting. I was getting encouragement at last, and I was learning and growing.

DA: It must feel strange to know there are websites devoted to teaching Bobbie Ann Mason.

BAM: I haven’t seen them. Who knew. I don’t really relate to my stories as texts for classroom study. I’m glad they are teaching them, but I am at a loss to imagine such discussions.

DA: How did you make the transition to writing novels.

BAM: I had written two novels before I began writing stories. My publisher wanted a novel, and I thought I could knock it off in a summer! But In Country was written in fits and starts and long silences. It took a long time to find the story. It didn’t evolve out of any specific story. I knew no one who had been in Vietnam. It wasn’t a personal story. And I was afraid to write about Vietnam. So I backed into the story and gradually found my way.

DA: What was it like seeing In Country translated to film?

BAM: After I finished writing In Country, I didn’t want to let the characters go, I had become so fond of them. The movie was like a gift, a chance to see them again in a somewhat different way, to see mental images made tangible. The movie was simpler, of course, but I appreciated the respect and seriousness of the movie-makers. And it was a vary big deal in my hometown for a movie to be made there. That was important, especially for the Vietnam vets.

DA: Clear Springs tells story of three generations of your family. Was it difficult to write?

BAM: It was, partly because it was so “literary.” I wrote it like a novel, with complex strands of imagery and plot. It’s not a simple, straightforward memoir. It is very selective, with interweaving stories. It’s the story of three generations of an American family that goes throughout the twentieth century, with dips back into the nineteenth. It is about language. It’s about the cultural shift in three generations occasioned by World War II. On the level that was my own story, it was about the education and sensibility of a writer.

DA: Once upon a time you wrote a short bio on Elvis Presley.

BAM: James Atlas asked me to write about Elvis for the Penguin Lives series. He sensed an affinity between me and the world Elvis came from. It wouldn’t have occurred to me, but once I got into the world of Elvis, it was very absorbing. It was such a sad story, and I think the world at large didn’t understand him. I tried to approach him via his background — his region, his parents, his culture. He had become a joke, and I hated that. It was very clear to me why he wore sequined jumpsuits and splurged on food and cars, and that is very sad. Elvis did the best he could in the extraordinary circumstances in which he found himself.

DA: What comes next?

BAM: I’m in transition, trying to catch up with my life. I’m not ready to jump into another novel yet. Last year I was busy with The Girl in the Blue Beret. I gave a reading at Shakespeare and Company in Paris. That was the highlight of the year! And the novel has an afterlife. I am still immersed in World War II and with the lovely friends I made while researching the material in Paris.